In a welcome break from election trauma, the usual Trump v. Clinton opining across my social-media feeds has been balanced this week by a different argument: “It’s high time Bob Dylan won the Nobel” v. “It’s a travesty Bob Dylan won the Nobel.”

Even amid my curation of friends and followers — heavily weighted as each set is with fellow folks and folkies in the orbit of the Woody Guthrie Center and that same city's new Bob Dylan Archive — the split has been nearly half and half. Like the presidential polls, such overall ambivalence is surprising, particularly because this particular box of Pandora’s has been wide open for some time. What’s been especially astonishing to me, anyway, is the vehemence with which some fans — of literature, not necessarily of Bob — cling to an outmoded compartmentalization of mediated experience.

0 Comments

The movie about Trump’s rise to power — his steamrolling of typical political strategies, his wielding of entertainment and emotion over policy and fact, his irascible irresistibility in the face of plodding traditionalism — was made more than 20 years ago. It’s called “Bob Roberts.” It’s a great “mockumentary,” but, like “Idiocracy,” it’s no longer very funny now that real life in America seems to be taking the gag seriously.  I’ve been trying to define what kind of scholar I am for five years now. My answer remains fluid — a bit more like Silly Putty now, but not yet firm like concrete — perhaps to the dismay of my current adviser. The journey of discovery is a more finely honed process than initially expected. Arriving in grad school, I simply thought I’d be trained to become a scholar — you know, like every other scholar. Of course, I quickly learned that this involved a game of Twister, placing hands and feet on established fields, theoretical perspectives, and myriad schools of thought, as well as playing tug-of-war with my own critical insights, situated knowledges, and bees in various bonnets. Thankfully, my first cohort (at UI-Chicago) happened to be one that landed in front of Kevin Barnhurst for class one, semester one: Philosophy of Communication. The Shadow, a vigilante crime fighter in an eponymous early 20th-century radio drama, foiled evildoers by using his supernatural power to cloud others’ minds to mask his own physical and psychological presence. Each program began with the narrator’s tagline: “Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men? The Shadow knows!”

The characters in “Noon at Dusk” — a new chamber opera by composer Stephen Lewis and librettist Yi Hong Sim (a colleague of mine at UCSD), recently premiered at UC-San Diego’s Conrad Prebys Music Center Experimental Theater — possess little criminal or evil intent, yet they likewise struggle against shadows and cloudy judgment. Across an inventive narrative arc and shot through with unsettling music, two couples face shadows of themselves and must consider precisely what lurks within their own hearts. My two most productive research interests seem quite different. My current dissertation project investigates the cultural histories and spatial embodiment of holograms and hologram simulations. In my copious free time (cough, sputter), I also maintain a course of study that began well before my grad-school adventure; as a journalist, both in Tulsa, Okla., and at the Chicago Sun-Times, I wrote a great deal about folksinger Woody Guthrie and the revival of his legacy within his home state, and now as a scholar I continue examining the ol' cuss and his peculiar communication strategies. One interest is old, analog, and sepia-toned; the other is shiny, digital, and futuristic.

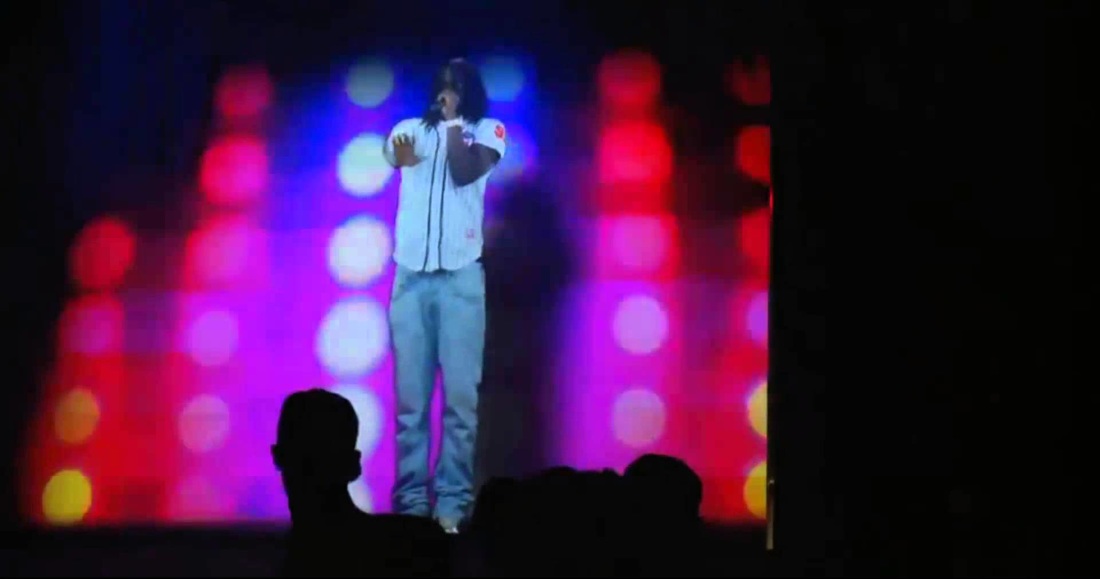

But — as I explained in my presentation this weekend at the Woody Guthrie Symposium, hosted jointly by The University of Tulsa and the Woody Guthrie Center — there's actually a bit of Venn-diagram shade between the two. What interests me about these emerging "hologram" technologies, especially uses of the tech in pop-music performance contexts, is how the digitally projected characters achieve some semblance of believability, how their creators manage to craft a successful performing persona, and whether these simulations can claim something like Benjamin's "aura" or even Bazin's "fingerprint." This is not far removed, I'd say, from the process human performers go through in crafting their own performing personas — which is what I claim Woody did during his two years on L.A. radio beginning in 1937, as a direct result of his encounter with the new mass medium and its delayed feedback channels. Such is the basis of my paper on the subject, and my talk this weekend. No one, to my knowledge, yet has proposed that Woody be among the legions of dead musicians resurrected in hologram form. This sounds like both a terrific idea (he'd probably love it) and a dreadful idea. Who knows?  This month saw publication of The Oxford Handbook of Music & Virtuality, containing my chapter, "Hatsune Miku, 2.0Pac and Beyond: Rewinding and Fast-forwarding the Virtual Pop Star." In it, I survey a history of virtuality in pop music stars, from the Chipmunks and the Archies up to Gorillaz and Dethklok — many of the non-corporeal, animated characters that presaged current virtual pop stars like Hastune Miku and the Tupac resurrection. Reports of David Bowie’s death had been exaggerated since the turn of this century. Even before his 2004 collapse on stage at a music festival in Germany, which resulted in an emergency angioplasty to clear a blocked artery, his penchant for keeping to his adult self fueled more-than-occasional rumors about his earthly condition. The Flaming Lips went so far as to title a 2011 joint single with Neon Indian “Is David Bowie Dying?” When he finally popped up in 2013 to debut a new single, fans overlooked the song’s maudlin nostalgia out of simple relief that he was alive and working. Tony Visconti, meanwhile, kept assuring us, “He’s not dying any time soon, let me tell you.”

Would that it were true. How could Bowie die, anyway? Surely there was no messy mortal at the center of all that radiant expression of life. Surely he was just a manifest Foucaultian process, an anthropomorphized discursive object, never actually material. At most, should the time come, he’d simply act out his departure as depicted on “The Venture Brothers” — saying, “Gotta run, love,” changing into an eagle, and flying away. When the news arrived on Monday, reality bit. As Bowie sang in the title track to his “Reality” album, “Now my death is more than just a sad song.” I wasn’t even the biggest Bowie fan in the world, not by a long shot, yet it was hard to concentrate for the rest of the day. Bowie the fountainhead flows through so much of the cultural landscape; I am the biggest fan of many folks who wouldn't have had careers, wouldn't have had the courage, without the lifeblood of that flow. Watered by his life, droughted by his death. I sat in my campus office, trying to work while listening to “Blackstar,” and a creeping dread arrived: How am I going to explain Bowie to my students? What is a hologram?

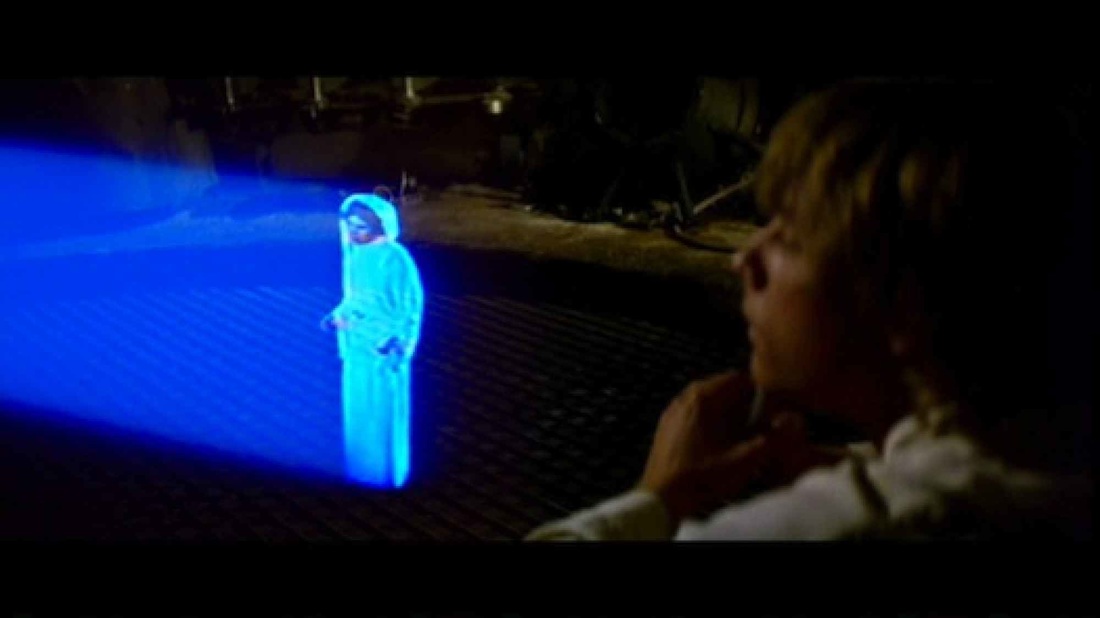

Dictionaries say one thing, but popular discourse says much more. From its birth as a collage of post-WWII optical sciences through the 1970s, holography was an evolving but fairly easily defined practice. Its products were called holograms — photo-like film images that delivered a more three-dimensional view of the subject. Then "Star Wars" happened. And write the obit when you do

He never ran out when the spirits were low A nice guy as minor celebrities go — Scott Miller, “Together Now, Very Minor” I’ve been rightly accused of liking Beatlesque bands better than the actual Beatles. True, give me Big Star over the Fab Four any day. But given how rarely either band actually figures into my everyday universe, my dispositions are even one more generation removed. Truer, give me Scott Miller over Alex Chilton any other day. When researching and writing about (or designing and producing) hologram simulations, there’s always an initial coming-to-terms with the terms.

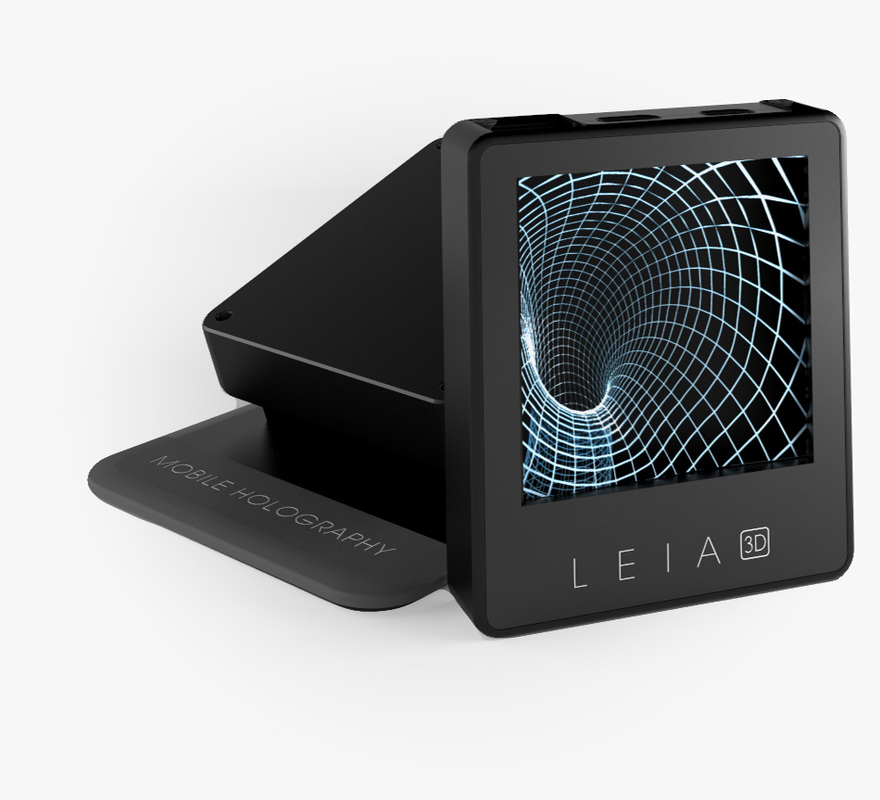

When I analyzed the discourses of simulation designers, nearly all of them made some attempt to square and/or pare the language of their field. Designers and artists usually opened interviews with this, eager to make sure I understood that while we call these things “holograms” they’re not actual holography. “The words ‘hologram’ and ‘3D,’ like the word ‘love,’ are some of the most abused words in the industry,” one commercial developer told me. Michel Lemieux at Canada’s 4D Art echoed a common refrain: “A lot of people call it holography. At the beginning, 20 years ago, I was kind of always saying, ‘No, no, it’s not holography.’ And then I said to myself, ‘You know, if you want to call it holography, there’s no problem.’” In my own talks and presentations, I’ve let go of the constant scare-quotes. The Tupac “hologram” has graduated to just being a hologram. It gets stickier when we begin parsing the myriad and important differences between virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR). Many of us think we have an understanding of both, largely as a result of exposure to special effects in movies and TV — where the concept of a hologram underwent its most radical evolution, from a mere technologically produced semi-static 3D image to a computer-projected, real-time, fully embodied and interactive communication medium — but it’s AR people usually grasp more than VR. They’ll say “virtual reality,” but they’ll describe Princess Leia’s message, the haptic digital displays in “Minority Report,” or the digital doctor on “Star Trek: Voyager.” Neither of these are VR, in which the user dons cumbersome gear to transport her presence into a world inside a machine (think William Gibson’s cyberspace or jacking into “The Matrix”); they are AR, which overlays digital information onto existing physical space. Yet both VR and AR refer to technologies requiring the user to user some sort of eyewear — the physical reality-blinding goggles of OculusRift (VR) or the physical reality-enhancing eye-shield of HoloLens (AR). Volumetric holograms — fully three-dimensional, projected digital imagery occupying real space — remain a “Holy Grail” (see Poon 2006, xiii) in tech development, and we may need a new term with which to label that experience. One developer just coined one. Black lives matter, yes. But what about black holograms?

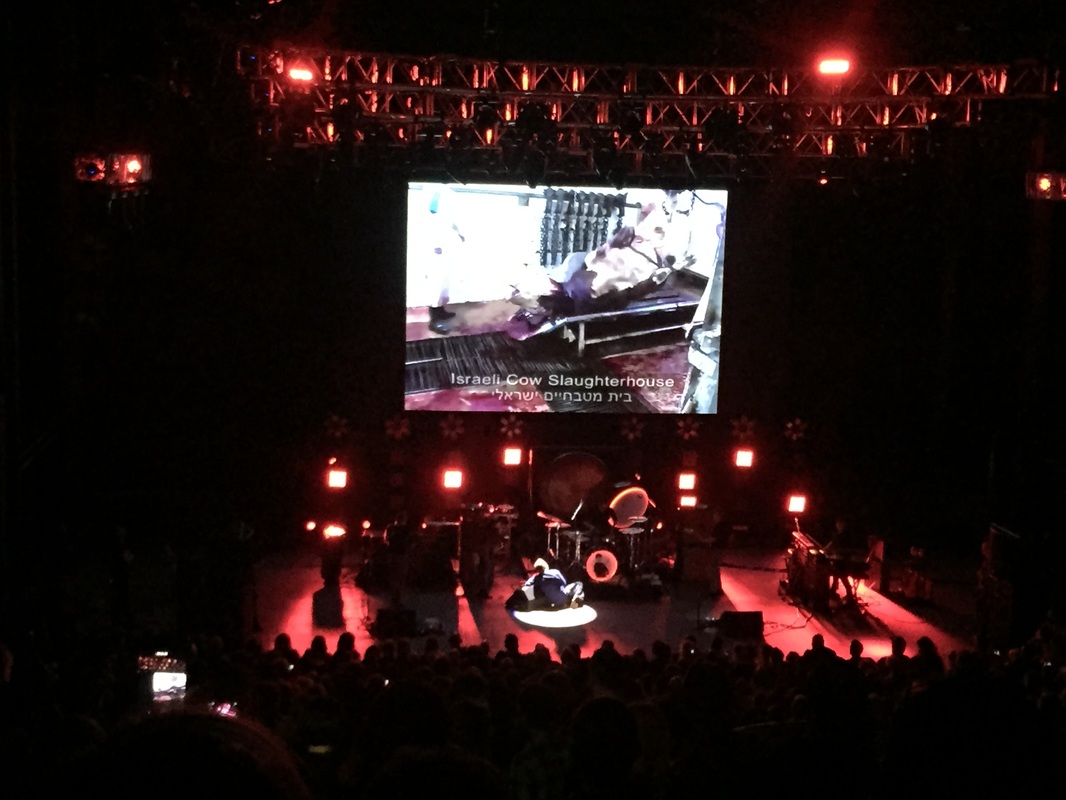

The criminalization of black bodies apparently extends to their digital form, as well. This important lesson came to us via Chicago rapper Chief Keef, who a couple of weeks ago attempted to perform in concert as a hologram simulation; his digital body, however, was powered down and prevented from performing in the same manner as his physical body. It’s a weird case of police overreach and an interesting example of how culture is still trying to get its collective head around the meanings of hologram simulations. I just returned from Denver, where my best friend David and I saw Morrissey in concert at Red Rocks. I’d intended merely to wax nostalgic about this — we’d seen him on his first solo tour in ’91, also in Denver, and I’ve much to say about how rewarding it’s been to grow old with Moz — but something he did at the end of his show makes for a poignant follow-up to my previous ramblings about the evolution of protest music performance.

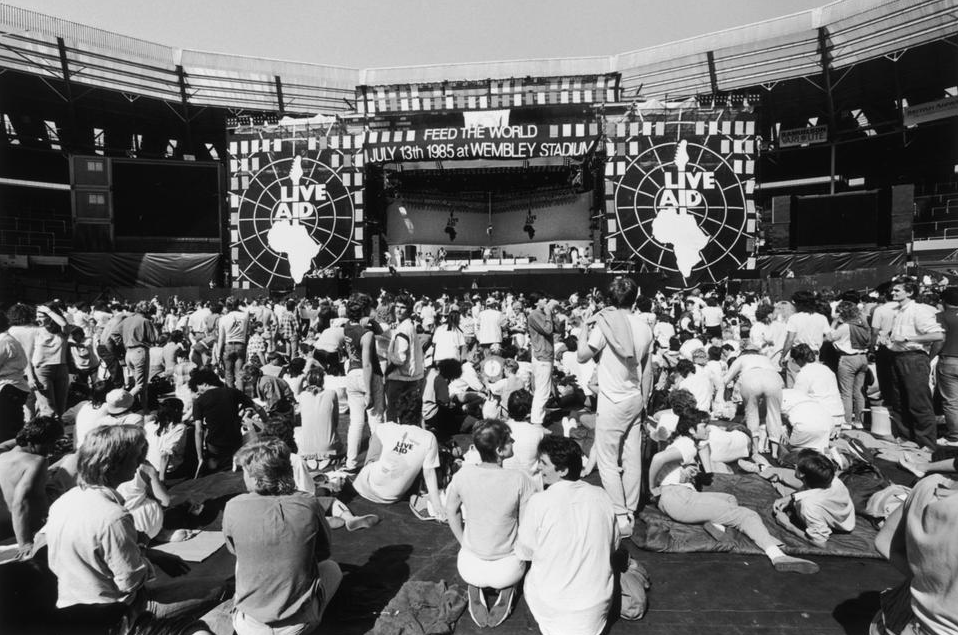

This week marks the 30th anniversary of Live Aid. Memory flashes I’m still able to conjure from my aging brain: Paul Young’s flouncy pirate cuffs, the poetic irony of Geldof’s mic failing during his own set, Elvis Costello’s classy choice of "an old northern English folk song," the Pretenders’ playing surprisingly laid-back, of course U2’s career-making set and Queen’s delivery of the world’s quintessential arena-rock performance. Political opinions aside, it was an unequaled day of, let’s say, musical performativity.

The DVD set of the concerts bears a postmark-like stamp that reads, “July 13, 1985: The day the music changed the world.” Thirty years have allowed for much evaluation of nearly all the changes wrought (not all for the better; read this excellent piece about Live Aid’s “corrosive legacy”). What it did change — drawing from research I conducted a few years ago into protest music (or the lack thereof) at Occupy Wall Street events — was the common conception of popular musical protest practice, resituating it from the open street to the ticketed arena, as well as the establishment of celebrity at the very core of such practices. The film “2010” — the 1984 sequel to the vaunted “2001” adaptation from ’68 — opens with its protagonist facing a huge decision: whether or not to embark on a long mission fraught with danger while prone to both failure and a threat to his marriage. He soon wakes up far from home in a bewildering technical environment among a cohort that speaks a different language. They struggle to collaborate on their first project, a research mission in which they find something unexpected, some groundbreaking new knowledge. Then their computer crashes and erases all the new data.

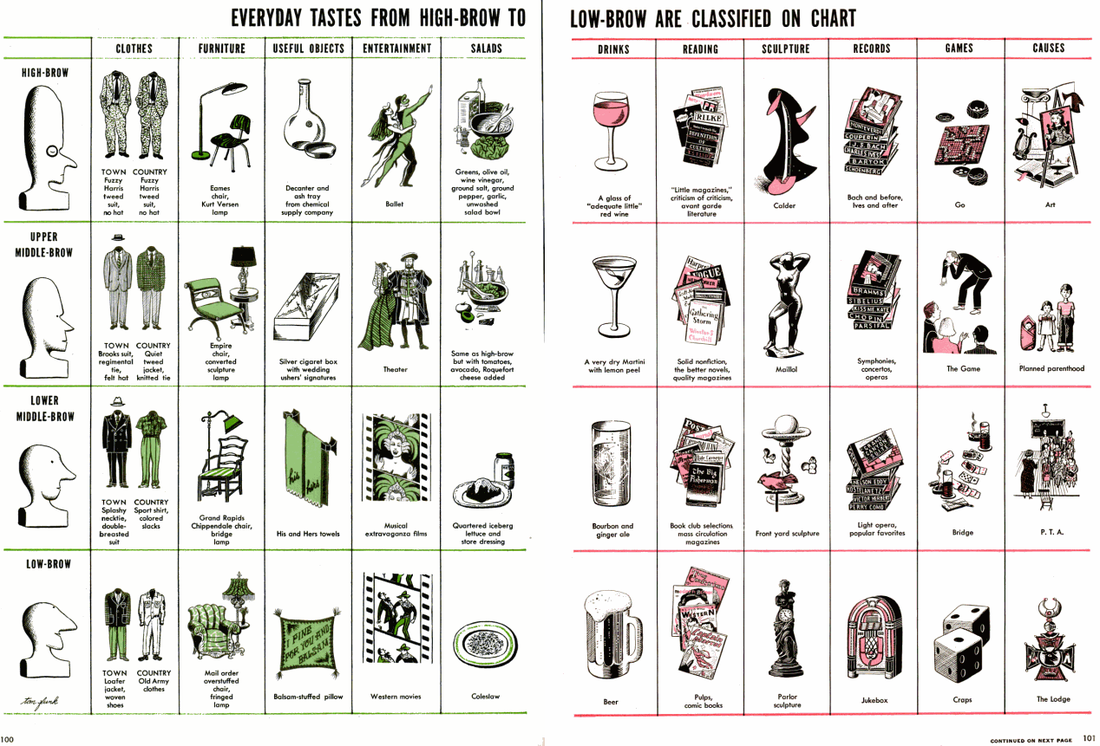

I see it now. It’s a movie about grad school. Saul Bellow was born a hundred years ago today, and people of letters have been spilling a lot of them in appreciation of and retrospection on his considerable work as a very American novelist. As it happens, this spring is also the centenary of a pivotal moment in those same American letters — the expression of a problematic idea that still haunts cultural discourses and one that speaks directly to Bellow’s particular literary tactics: publication of Van Wyck Brooks’ claims about this country’s great divide between “highbrow” and “lowbrow” cultures.

|

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed