|

It's the first week of classes at The University of Tulsa, where I'm a new Visiting Assistant Professor of Media Studies. My upper-division seminar is Music as Social Action, a theoretical and historical survey of American protest songs. And wouldn't you know it — a protest song just went viral around the country. Given this confluence — and the fact that stories about the song keep tagging Woody Guthrie and Billy Bragg, with whom I have some considerable personal experience — I had some thoughts. My colleagues at the Tulsa World were good enough to print them.

0 Comments

Jimmy LaFave left Oklahoma as a young man — just like one of his biggest heroes, Woody Guthrie — then lived an entire life continually inspired by the red dirt he left behind, haunted by his homestate histories, and consistently pressed into service as an ambassador for its culture. He didn’t seem to mind. “There’s something about that part of the earth that sticks with you,” he told the Tulsa World nearly 15 years ago. “I have to go back there from time to time to soak up some energy and inspiration. I plan to end up back there myself one day.” I don’t know if he’s ultimately ending up back in Oklahoma, but I’d always been convinced he never actually left.

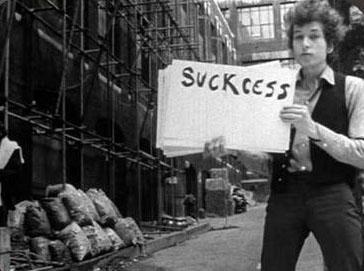

In a welcome break from election trauma, the usual Trump v. Clinton opining across my social-media feeds has been balanced this week by a different argument: “It’s high time Bob Dylan won the Nobel” v. “It’s a travesty Bob Dylan won the Nobel.”

Even amid my curation of friends and followers — heavily weighted as each set is with fellow folks and folkies in the orbit of the Woody Guthrie Center and that same city's new Bob Dylan Archive — the split has been nearly half and half. Like the presidential polls, such overall ambivalence is surprising, particularly because this particular box of Pandora’s has been wide open for some time. What’s been especially astonishing to me, anyway, is the vehemence with which some fans — of literature, not necessarily of Bob — cling to an outmoded compartmentalization of mediated experience. My two most productive research interests seem quite different. My current dissertation project investigates the cultural histories and spatial embodiment of holograms and hologram simulations. In my copious free time (cough, sputter), I also maintain a course of study that began well before my grad-school adventure; as a journalist, both in Tulsa, Okla., and at the Chicago Sun-Times, I wrote a great deal about folksinger Woody Guthrie and the revival of his legacy within his home state, and now as a scholar I continue examining the ol' cuss and his peculiar communication strategies. One interest is old, analog, and sepia-toned; the other is shiny, digital, and futuristic.

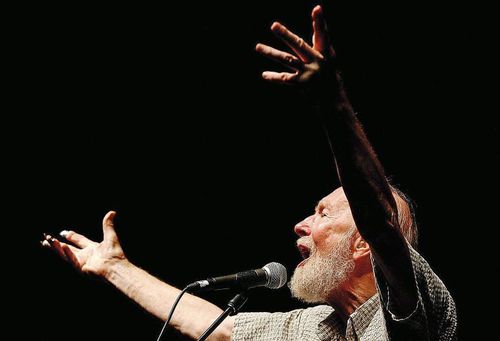

But — as I explained in my presentation this weekend at the Woody Guthrie Symposium, hosted jointly by The University of Tulsa and the Woody Guthrie Center — there's actually a bit of Venn-diagram shade between the two. What interests me about these emerging "hologram" technologies, especially uses of the tech in pop-music performance contexts, is how the digitally projected characters achieve some semblance of believability, how their creators manage to craft a successful performing persona, and whether these simulations can claim something like Benjamin's "aura" or even Bazin's "fingerprint." This is not far removed, I'd say, from the process human performers go through in crafting their own performing personas — which is what I claim Woody did during his two years on L.A. radio beginning in 1937, as a direct result of his encounter with the new mass medium and its delayed feedback channels. Such is the basis of my paper on the subject, and my talk this weekend. No one, to my knowledge, yet has proposed that Woody be among the legions of dead musicians resurrected in hologram form. This sounds like both a terrific idea (he'd probably love it) and a dreadful idea. Who knows? The life of Pete Seeger inspired a lot of wonderful words this week — eulogies, appreciations, retrospectives, think pieces, memories from Arlo, one singularly stupendous comic strip — and I could write a lot more. I’ll keep my belated memories brief, because Woody Guthrie’s own summation of his friend, below, is just about the best thing worth reading (and reading aloud) in remembrance of one of the greatest cultural figures this country ever produced, a living archive of every generation thus far of American folk music.

UCSD’s theater dept. is mounting a production of “The Grapes of Wrath” this month — Frank Galati’s superlative stage adaptation of John Steinbeck’s landmark novel. Galati won a pair of Tonys after initially bringing this story to the stage at Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theatre Co., and my former colleague, theater critic Hedy Weiss, described the adaptation’s faithfulness to the source material as “not only uncompromising, but devoid of sentimentality, and that it is flawless in the way it sweeps us into the lives of the characters, and their time, without a wasted word or motion.” Hard to go wrong with source material this great.

Just a couple of weeks ago, I was hanging with the Joads myself. |

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed