|

In many of my media-studies courses, we usually begin by underlining the idea that all communication is mediated. Some students initially resist this. They see conversation and face-to-face interactions as direct, unmanaged, unmediated — communing rather than communicating. Once we get going, though, they learn to see the mediation in play even here: gestures and visuals, language itself, social forces, and the very spaces of interaction. There is no mind meld. There’s always a mediator.

Many emerging media, however, would like their users to think like those hesitant students — to experience the pre-programmed interactions of their technologies as unmediated, to ignore the inherent and carefully managed structure of the encounter, to assume that the communication is direct and free of outside influence. Thus the rapid development of digital channels that seem more “natural.” ChatGPT and other AI systems free users from having to learn a particular communication code; instead of mastering the art of the Boolean query in order to maximize Google results, ChatGPT speaks our language, as it were. Ask it a complete, “normal” question, and receive an almost human response rather than formatted results. Siri, Alexa, and other voice assistants create seemingly interpersonal encounters via natural language, as if we’re conversing easily with another subject rather than interrogating a bot. Only when the systems make mistakes do they become more visible in the exchange and remind us that, oh right, I’m talking to a machine. To further understand this kind of situation — and especially in the context of my investigations related to digital holograms, which only succeed as communication if their mediating apparatus is similarly hidden from the user’s experience — it may be useful to adopt a theory that was coined in the context of literature and art and adapt it within media studies: demediation.

0 Comments

Last day of Media History class, and I threw ’em a one-two punch. First, we read some of Vilém Flusser’s intentionally provocative media philosophy — where he claims that the age of writing is ending. Then, per the 21C prof handbook, we pivoted to a YouTube video (above) about hip-hop writing practices. The class basically started with writing — what was it? what is it? what does it do? — so I wanted to bookend the semester by circling back. After spending the second half of the term immersed in mostly electronic media, indeed, what’s the status of this allegedly foundational linear-narrative form? Ever since I read this book in 2022, I’d been looking for the right syllabus — OK, any syllabus — that could support its wonderful weirdness. Written by a musician, it’s one of the finest theoretical texts about cultural materialism I’ve ever savored. And it’s all about a spent piece of chewing gum. A new journal article of mine is now published: "Rock and Roll Will Never Die: Holograms and the Spectrality of Performance" in the spring issue of Spectator, the film-studies journal at USC. The work extends a conference presentation I gave at USC's First Forum in 2021. The abstract: In 2012, the rapper Tupac Shakur performed in the top slot at a major music festival — an event only notable because he had died 16 years earlier. The performance was made possible by a 21st-century digital upgrade of a 19th-century stage illusion called Pepper’s Ghost, and it ushered in a trend of creating and presenting similar “hologram” performances of posthumous pop stars. This article offers an explanation of what is seen in such a performance, examining the simulation of 3D video imagery designed to veil its mediation in order for its subject to appear unmediated, present, and “real.” Ultimately, I claim that these illusions are contemporary séances — a revival of historically spiritualist practices but one in which what is conjured is actually the deceased’s previously existing performing persona, as the concept has been extended by Philip Auslander. This cultural entity (distinct from the body and able to outlive it) is offered a new embodiment within a media system that restores the immaterial entity to the material space of the stage — a context previously off limits to the dead performer. Read the article here!

I've written before here about David Gunkel's research and thoughts on the social rights of robots. He's now summed up the many arguments for and against — and contributed his own, based on the philosophy of Levinas — in a new book, Robot Rights, from MIT Press. I jumped at the chance to review it, and it's finally published online.

And, hey, Gunkel referred to my review as "positively brilliant"!  Science for the People was an organization of scientists and science workers who banded together around the turn of the ’70s to express concerns about the commercialization, industrialization, and militarization of science. The group raised awareness of a multitude of issues, organized and balanced public debates (which sometimes included disrupting establishment conferences), and published a spiffy magazine for nearly a decade. Worried about how science was being used against people, SftP advocated for. In 2014, a conference was organized at UMass-Amherst to examine the group’s legacy. At the close of the event, several attending students and scholars from across the country met to discuss ways to continue the examination, even ways to revive and evolve the mission of SftP. I was fortunate to be among this group, and the result of our decision has finally been realized in a new book: Science for the People: Documents From America’s Movement of Radical Scientists, now available.  I’ve been trying to define what kind of scholar I am for five years now. My answer remains fluid — a bit more like Silly Putty now, but not yet firm like concrete — perhaps to the dismay of my current adviser. The journey of discovery is a more finely honed process than initially expected. Arriving in grad school, I simply thought I’d be trained to become a scholar — you know, like every other scholar. Of course, I quickly learned that this involved a game of Twister, placing hands and feet on established fields, theoretical perspectives, and myriad schools of thought, as well as playing tug-of-war with my own critical insights, situated knowledges, and bees in various bonnets. Thankfully, my first cohort (at UI-Chicago) happened to be one that landed in front of Kevin Barnhurst for class one, semester one: Philosophy of Communication.  This month saw publication of The Oxford Handbook of Music & Virtuality, containing my chapter, "Hatsune Miku, 2.0Pac and Beyond: Rewinding and Fast-forwarding the Virtual Pop Star." In it, I survey a history of virtuality in pop music stars, from the Chipmunks and the Archies up to Gorillaz and Dethklok — many of the non-corporeal, animated characters that presaged current virtual pop stars like Hastune Miku and the Tupac resurrection. When researching and writing about (or designing and producing) hologram simulations, there’s always an initial coming-to-terms with the terms.

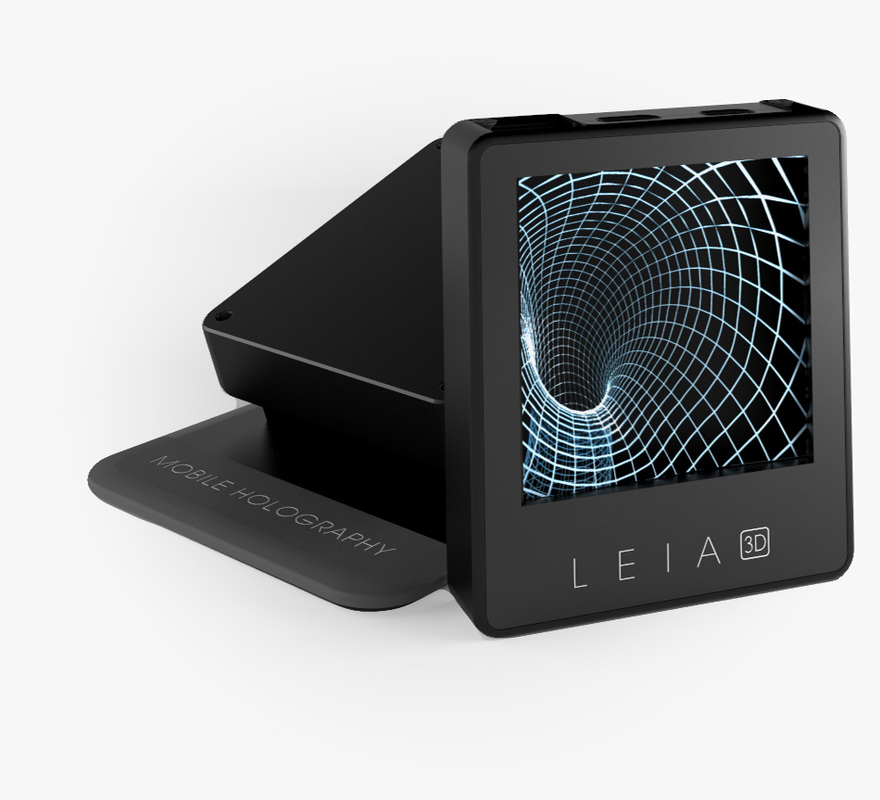

When I analyzed the discourses of simulation designers, nearly all of them made some attempt to square and/or pare the language of their field. Designers and artists usually opened interviews with this, eager to make sure I understood that while we call these things “holograms” they’re not actual holography. “The words ‘hologram’ and ‘3D,’ like the word ‘love,’ are some of the most abused words in the industry,” one commercial developer told me. Michel Lemieux at Canada’s 4D Art echoed a common refrain: “A lot of people call it holography. At the beginning, 20 years ago, I was kind of always saying, ‘No, no, it’s not holography.’ And then I said to myself, ‘You know, if you want to call it holography, there’s no problem.’” In my own talks and presentations, I’ve let go of the constant scare-quotes. The Tupac “hologram” has graduated to just being a hologram. It gets stickier when we begin parsing the myriad and important differences between virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR). Many of us think we have an understanding of both, largely as a result of exposure to special effects in movies and TV — where the concept of a hologram underwent its most radical evolution, from a mere technologically produced semi-static 3D image to a computer-projected, real-time, fully embodied and interactive communication medium — but it’s AR people usually grasp more than VR. They’ll say “virtual reality,” but they’ll describe Princess Leia’s message, the haptic digital displays in “Minority Report,” or the digital doctor on “Star Trek: Voyager.” Neither of these are VR, in which the user dons cumbersome gear to transport her presence into a world inside a machine (think William Gibson’s cyberspace or jacking into “The Matrix”); they are AR, which overlays digital information onto existing physical space. Yet both VR and AR refer to technologies requiring the user to user some sort of eyewear — the physical reality-blinding goggles of OculusRift (VR) or the physical reality-enhancing eye-shield of HoloLens (AR). Volumetric holograms — fully three-dimensional, projected digital imagery occupying real space — remain a “Holy Grail” (see Poon 2006, xiii) in tech development, and we may need a new term with which to label that experience. One developer just coined one. The film “2010” — the 1984 sequel to the vaunted “2001” adaptation from ’68 — opens with its protagonist facing a huge decision: whether or not to embark on a long mission fraught with danger while prone to both failure and a threat to his marriage. He soon wakes up far from home in a bewildering technical environment among a cohort that speaks a different language. They struggle to collaborate on their first project, a research mission in which they find something unexpected, some groundbreaking new knowledge. Then their computer crashes and erases all the new data.

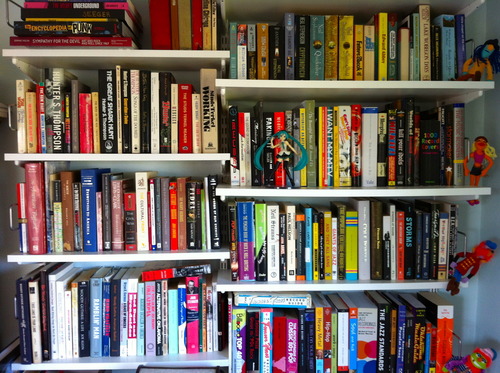

I see it now. It’s a movie about grad school. Life is great like this: I spent an afternoon this week unpacking the remainder of my library (delayed, as often happens, months after moving in), and basking in the intense comfort of having treasured volumes once again within reach; then, I sat down with a well-earned cocktail and opened Illuminations, a collection of Walter Benjamin essays recently added to my to-read shelf — and what to my wondering eyes should appear but the anthology’s first selection: “Unpacking My Library.”

The Tao that can be explained is not the enduring and unchanging Tao.

— Lao Tzu Before beginning my graduate communication studies, I knew I was entering a conflicted field. The fact that every scholar I’ve spoken to or studied with defines communication slightly differently and citing different theoretical perspectives is exciting, not daunting — and, surprisingly, not that confusing. It is large, this field; it contains multitudes. Translation: there’s still much to be done — more than ever, now that the communication of information is a vaunted pillar of modern society — so come on aboard. Thus, a new missive questioning the standing, ambition and overall health of communication scholarship — “Communication Scholars Need to Communicate” by USC Annenberg’s dean, the earnest Ernest J. Wilson III — is merely the latest in a long series of semi-perennial glances toward our brainy navels. The field, it seems, is still fermenting. |

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed