|

The film “2010” — the 1984 sequel to the vaunted “2001” adaptation from ’68 — opens with its protagonist facing a huge decision: whether or not to embark on a long mission fraught with danger while prone to both failure and a threat to his marriage. He soon wakes up far from home in a bewildering technical environment among a cohort that speaks a different language. They struggle to collaborate on their first project, a research mission in which they find something unexpected, some groundbreaking new knowledge. Then their computer crashes and erases all the new data. I see it now. It’s a movie about grad school. End of quarter, end of year. This, I’m learning, is usually followed by about a week of utter sloth and binge-watching brain-drain. While curled up on the sofa this week, staring at anything that will have me, I once again watched this fabled sequel. Granted, not surprising given my current context, but the parallels just kept coming at me.

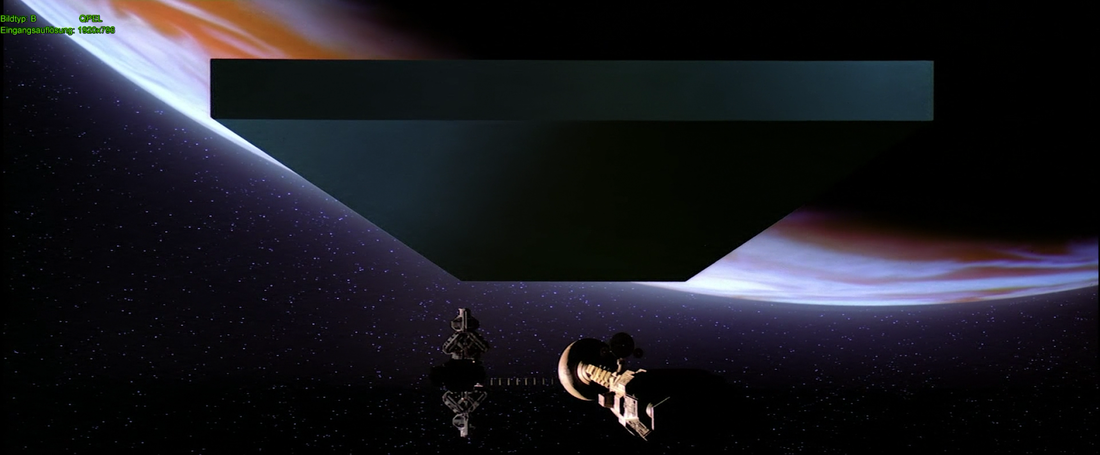

The whole narrative is about a media archaeology project — retrieving a failed technology, trying to contextualize its failures and how those are connected to the present. Characters are each pushed out of their comfort zones; John Lithgow, before stepping into the void, says — voicing a familiar sentiment — “I’m not an astronaut. I’m an engineer. What the hell am I doing?” There’s even a heated debate about whether to send a manned probe (ethnography!) or to study the new phenomenon through mediated tech. Dr. Chandra (the great Bob Balaban, not long after talking to the SAL-9000, voiced by Candace Bergen): “Whether we are based on carbon or silicon makes no fundamental difference. We should each be treated with appropriate respect.” Yes, robot rights! Throughout the story, we hear constant assurances by an embodied intelligence that something’s going to happen, something wonderful — without any specifics as to what the hell that’s going to be. (Dave Bowman's ghost = all grad advisers?) Then there’s a big bang, a flood of illumination, and suddenly the universe is full of some brand-new knowledge, which unites opposing sides, busts binaries, and opens whole new vistas of exploration. The monolith looms as its own character in the movie — the central character. It’s the ultimate metaphor for one’s research, the “project,” The Dissertation. The monolith is the ultimate unknown. It begs for inquiry, demands pursuit, all the while keeping pursuers and researchers at a distance. It has no voice until humans describe it, explain it, account for its actions. (Latour’s ultimate actant? It’s certainly the definitive black box!) At the end, amid a soliloquy that sounds like a eulogy for the Dark Ages, Dr. Floyd narrates: “I still don’t really know what the monolith is. I think it’s many things … a shape of some kind for something that has no shape or parameters.” (Taoism alert: depending on translation, that phrase comes straight from stanza 14 of the Tao te Ching, or from Stephen Mitchell’s: “Form that includes all forms.”) Because in this story, we found out that, according to Arthur C. Clarke’s original vision, there’s not just one monolith; there were infinite numbers of them. Endless questions, endless answers.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed