|

In the early 1990s, folk-rocker John Wesley Harding released one of the best B-sides around: “When the Beatles Hit America.” A lengthy narrative about a dreamed-up Fab Four reunion, it envisions both cultural and technological contexts for a new Beatles event — and this is back when only one of them was dead. In Harding’s epic ballad, the Beatles are going to reunite on stage, all “due to a miracle marketing strategy / beyond the realms of reasonable possibility.” The lyrics realistically dramatize the build-up (securing the film rights, sponsorships, talk show scheduling, etc.) and then inject a bit of scifi to make it happen (the manager of the new Beatles is “made up of cloned parts of Col. Tom Parker and Col. Sanders”). Ringo won’t actually play, though, because he’s been replaced by a more accurate drum machine; he’s “disappointed to find that no one / needs him anymore except for the vibe.” Lennon, meanwhile, is substituted with a life-size cardboard cutout, and then — per today’s news, in a way — he speaks to the press, sounding suspiciously like some old recordings: John, who was never the quiet one makes all his press contributions from his old songs -- in tune, in time, and with the backing track behind him And when they ask him how it’s been in the studio, he says, “It’s been a hard day’s night” And no one understands him, but he always was the cryptic one … Funny stuff, but now prescient. Today marks the release of the Beatles’ latest — and allegedly last — technologically resurrected cast-off, a “new” old song called “Now and Then” that features the two living members and the two dead ones reunited in eerily perfect harmony and time. As a scholar who studies the uncanny properties of media and its inherent constructions of liminal spaces between life and death, well, I have some initial thoughts.

0 Comments

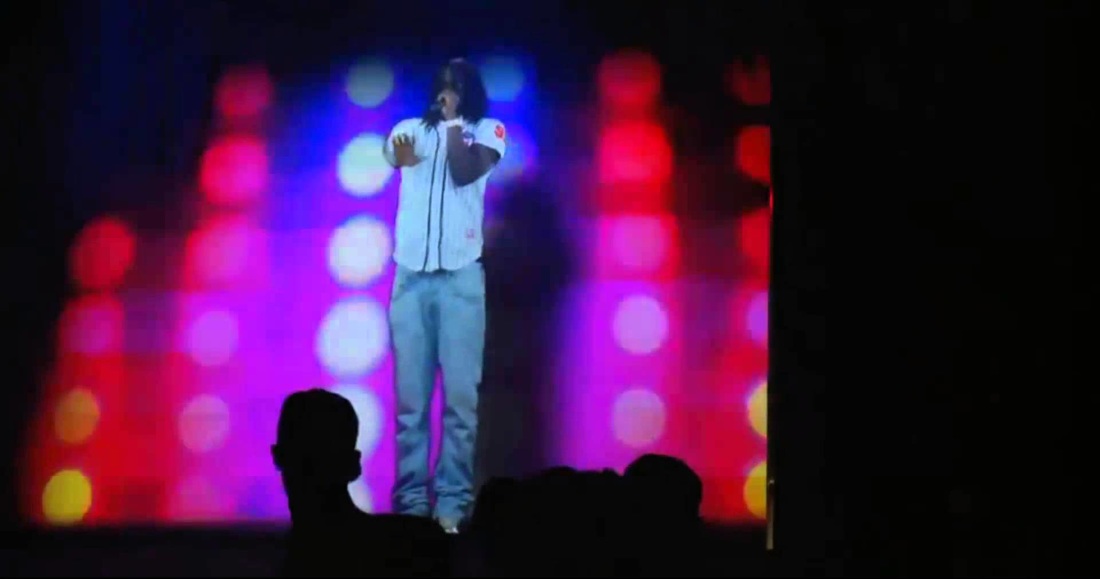

A new journal article of mine is now published: "Rock and Roll Will Never Die: Holograms and the Spectrality of Performance" in the spring issue of Spectator, the film-studies journal at USC. The work extends a conference presentation I gave at USC's First Forum in 2021. The abstract: In 2012, the rapper Tupac Shakur performed in the top slot at a major music festival — an event only notable because he had died 16 years earlier. The performance was made possible by a 21st-century digital upgrade of a 19th-century stage illusion called Pepper’s Ghost, and it ushered in a trend of creating and presenting similar “hologram” performances of posthumous pop stars. This article offers an explanation of what is seen in such a performance, examining the simulation of 3D video imagery designed to veil its mediation in order for its subject to appear unmediated, present, and “real.” Ultimately, I claim that these illusions are contemporary séances — a revival of historically spiritualist practices but one in which what is conjured is actually the deceased’s previously existing performing persona, as the concept has been extended by Philip Auslander. This cultural entity (distinct from the body and able to outlive it) is offered a new embodiment within a media system that restores the immaterial entity to the material space of the stage — a context previously off limits to the dead performer. Read the article here!

Raffi Kryszek, of PROTO Hologram, and myself before the panel at SDCC22. What a great time hosting a panel at Comic-Con in San Diego on Friday! A sizable crowd joined us for "From Scifi Imaginary to Tech Reality: The New Science of Holograms" — and, wow, did they ask superlative, knowledgeable questions! Panelists were myself and Raffi Kryszek, the principal hardware architect for the PROTO Hologram company in Los Angeles. (Tara Knight from Colorado U's Critical Media Studies program was unable to make it.)  I finally got the chance to show off one of the only vintage comic books I possess: a 1978 one-off called Holo-Man, about a doctor zapped by high energy in a holographic matrix, which grants him superpowers (projecting illusions, time travel, invisibility). We parsed the various ways holograms have remained ubiquitous throughout science-fiction narratives, evolving the imaginary of digitally projected matter and characters. Then Raffi discussed the exciting work being done at PROTO to actualize that imaginary — creating life-size, photo-real 3D simulations of people through its unique "hologram" technologies. He even clued us into the next new model (desktop-sized!). Good stuff and good fun! Thanks to the Comic-Con folks for having us! In this week’s episode of the CBS crime drama NCIS, detectives interview an unusual person of interest in a murder case: the victim herself.

Older narratives might have made this possible via a traditional spiritualist séance, with interested parties holding hands around a table as Madame Blavatsky channeled the spirit of the dead in order to ask directly, “Whodunnit?” In today’s séances, however, the medium has become digital media: complex technical imagery systems that archive a person’s likeness and prerecorded messages intended to be posthumously played back for survivors. Several such apparatuses exist already, though most are still in experimental and prototype stages. This NCIS episode, however, brings to the broader public a fairly accurate depiction of what such “holograms” currently look and seem like, as well as providing some early fodder for conversations about how they might be integrated into social realities. That is, people often ask, “Why in the world would you make a hologram of yourself?” Here’s a pop-culture text that starts grappling with a few real answers. Get Back — Peter Jackson’s extraordinary new reboot of Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s 1969 documentary footage following the Beatles’ penultimate recording sessions — has been revelatory in numerous ways, from its prompting of astute reconsideration of Yoko Ono’s much-maligned cultural narrative to final proof that Billy Preston utterly saved the day. The remarkable technology used to revive these old reels (and the audio) is important to attend to not only for its importance to the future of film restoration but for its increasing intrusion into filmmaking; Get Back is a highly computed film, perhaps the first movie many have seen with such dramatic and artistic contributions by an algorithm (“And the Oscar for Best Algorithm goes to…”?) — to the point that the documentary’s rotoscopic computation of imagery and sound can be seen as the construction of a kind of virtual reality.

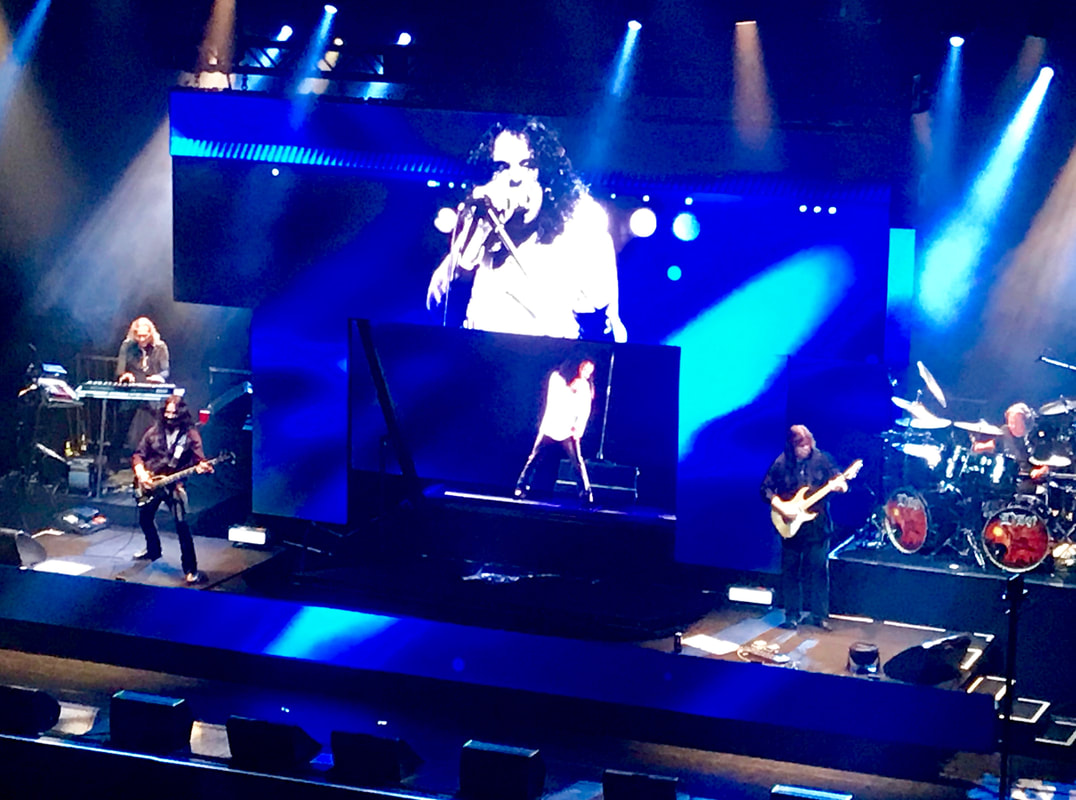

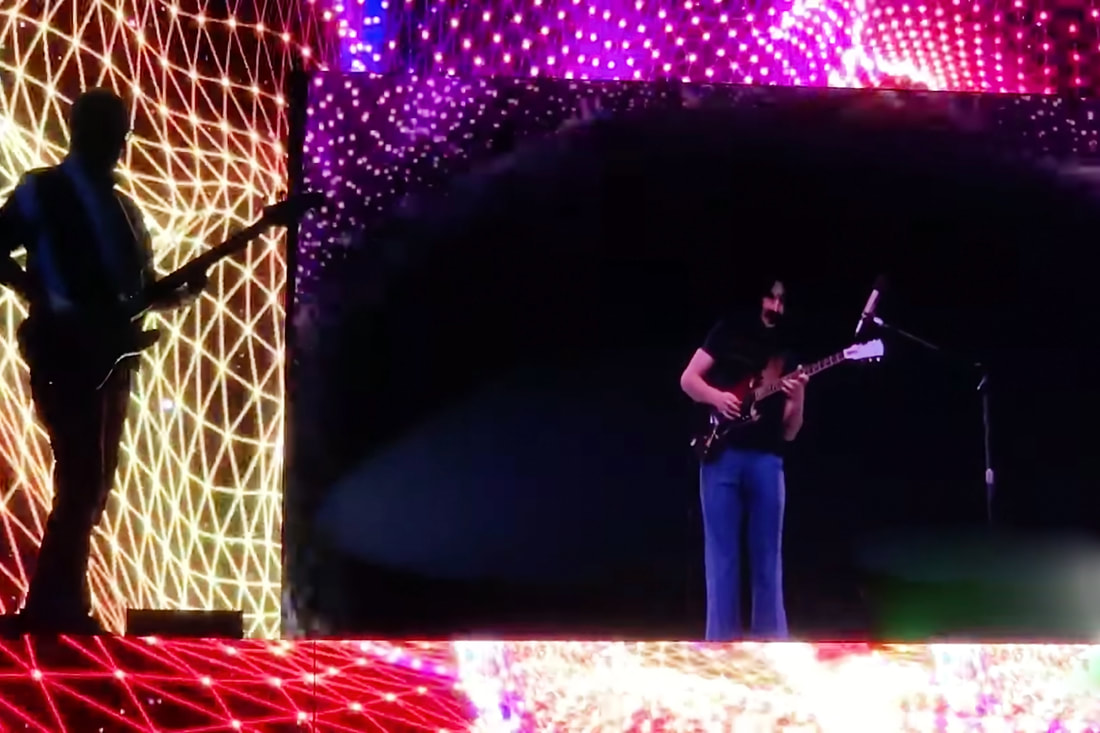

In addition to this surface virtuality of the image, however, I’m interested in the virtuality of the individuals shown through that imagery — and the ways Get Back is less a documentary about live human beings than it is about a socially constituted band of living ghosts. Several iterations of performing “holograms” have begun touring the country, as I’ve written about a bit here (and it’s a primary subject of my dissertation). The rolling out of these nascent, futuristic spectacles constitutes early technical and market experiments to determine whether audiences will engage with posthumous, digital pop stars as a going concern beyond the one-off spectacles of 2.0Pac and Michael Jackson. The subject matter selected for this first round of touring spectacles has been, in a word, niche. For instance, the late soprano Maria Callas has been making the rounds of international opera houses once again, in digital form. Likewise, dead crooner Roy Orbison just completed new tours of Australia and North America, and last week it was announced his hologram will return to the road on a double bill with Buddy Holly. We're not starting with the Beatles, in other words. Last weekend, a hologram of heavy metal singer Ronnie James Dio wrapped a 17-date U.S. tour with a final show in Los Angeles. I attended that show, and I offer some thoughts and observations here. Image linked from Rolling Stone “The Bizarre World of Frank Zappa” is a current concert tour featuring a resurrection of the title rocker as a “hologram” — the latest in a lengthening line of the digital deceased returning to stages. For instance, rock and roll pioneer Roy Orbison toured again last year and opera diva Maria Callas sang earlier this month in Los Angeles, where next month you also can check out the controversial Ronnie James Dio hologram. Each of these is an offspring of 2.0Pac — the “hologram” of the (allegedly) dead rapper that landed a headlining slot at the Coachella music festival in 2012. They are augmented-reality (AR) displays scaled to life-size: a visual likeness of the original star is recreated digitally, paired with archived audio, and projected onto a stage where the image “performs” alongside live, human musicians playing in sync.

It’s a phenomenon that should be generating fascinating visuals, breaking a stale mold of live musical performance, and inspiring new modes of both living and posthumous embodiment. But it’s not, at least not yet. Performing holograms thus far — even zany ol’ Zappa — are alarmingly conservative in their presentation and undemanding of their phenomenological experiences. For a technology inextricably linked to discourses of futurism and spectacle, the first wave of virtual pop stars has been disappointingly old-fashioned and dull. This post argues for some perspectives that might assist and direct the creative development of Holograms 2.0, with a nod toward last week's more interesting televised Madonna holograms. My research focuses on technologies that bring digital projections of dead people “to life,” in a sense (or several). Part of my historical work tracks particular reasons the word “hologram” has been so easily applied to resurrected performances of, for example, Tupac and Michael Jackson, despite these presentations and their apparatuses having nearly nothing in common with actual holography. That is, they are not precisely related technically. The spectral imagery produced by both, however — the life-sized human bodies and parts of bodies that are there but not there — are part of a lengthy project in certain corners of human culture. Holograms and “holograms,” as well as the Pepper’s ghost stage illusion, certain representational concepts on either side of Renaissance art, on back to occasional practices at the Delphic oracle — these are technical presentations that both reckon with the dead and create a media effect I call “holopresence.” So the new film Marjorie Prime — a chamber drama about four characters swapping their mortal bodies for posthumous digital “holograms” — was, you might imagine, a must-see. (Spoilers to follow) “What year is this?” It was an extraordinary last line for a wide variety of reasons. Aside from those relevant to the narrative, it’s a question I hear asked often of pop cultural events. Like: “Nintendo is releasing a mini NES? What year is this?” “Billy Idol is opening for Morrissey? What year is this?” Even and maybe especially: “A new season of Twin Peaks? What year is this?” Sunday night’s anticipated finale of Twin Peaks: The Return capped an extraordinary run of television. That certain chunks of this 18-hour avant-garde odyssey are out there in the stream now — for everyday channel surfers to just stumble upon — blows my happy mind. This post is not a review of the show — there are plenty of good ones out there now — but just a quick knocking together of some thoughts about the series’ intriguing engagement with representational technologies and death. (And it does contain spoilers!) Writing about Facebook profiles as memorials to the dead, Patrick Stokes notes that “our social identities are not necessarily coextensive with the biological life of the individual human organism with which they are associated, and thus it is not the memory of the dead person that is being honored and sustained through this form of memorialization, but some dimension or extension of the dead person themselves” (367). This is part of a growing body of literature that has coalesced around the agency of the dead — an agency facilitated specifically through durable, mediated representations of formerly living bodies.

My research is rooted in a sizable patch of this, but I’m commenting on some of it here because of a couple of nifty examples encountered just this week — mediated, shared, and hyped performances by two public figures who are no longer alive. (Warning: a few minor “Rogue One” spoilers lie ahead.) My two most productive research interests seem quite different. My current dissertation project investigates the cultural histories and spatial embodiment of holograms and hologram simulations. In my copious free time (cough, sputter), I also maintain a course of study that began well before my grad-school adventure; as a journalist, both in Tulsa, Okla., and at the Chicago Sun-Times, I wrote a great deal about folksinger Woody Guthrie and the revival of his legacy within his home state, and now as a scholar I continue examining the ol' cuss and his peculiar communication strategies. One interest is old, analog, and sepia-toned; the other is shiny, digital, and futuristic.

But — as I explained in my presentation this weekend at the Woody Guthrie Symposium, hosted jointly by The University of Tulsa and the Woody Guthrie Center — there's actually a bit of Venn-diagram shade between the two. What interests me about these emerging "hologram" technologies, especially uses of the tech in pop-music performance contexts, is how the digitally projected characters achieve some semblance of believability, how their creators manage to craft a successful performing persona, and whether these simulations can claim something like Benjamin's "aura" or even Bazin's "fingerprint." This is not far removed, I'd say, from the process human performers go through in crafting their own performing personas — which is what I claim Woody did during his two years on L.A. radio beginning in 1937, as a direct result of his encounter with the new mass medium and its delayed feedback channels. Such is the basis of my paper on the subject, and my talk this weekend. No one, to my knowledge, yet has proposed that Woody be among the legions of dead musicians resurrected in hologram form. This sounds like both a terrific idea (he'd probably love it) and a dreadful idea. Who knows?  This month saw publication of The Oxford Handbook of Music & Virtuality, containing my chapter, "Hatsune Miku, 2.0Pac and Beyond: Rewinding and Fast-forwarding the Virtual Pop Star." In it, I survey a history of virtuality in pop music stars, from the Chipmunks and the Archies up to Gorillaz and Dethklok — many of the non-corporeal, animated characters that presaged current virtual pop stars like Hastune Miku and the Tupac resurrection. What is a hologram?

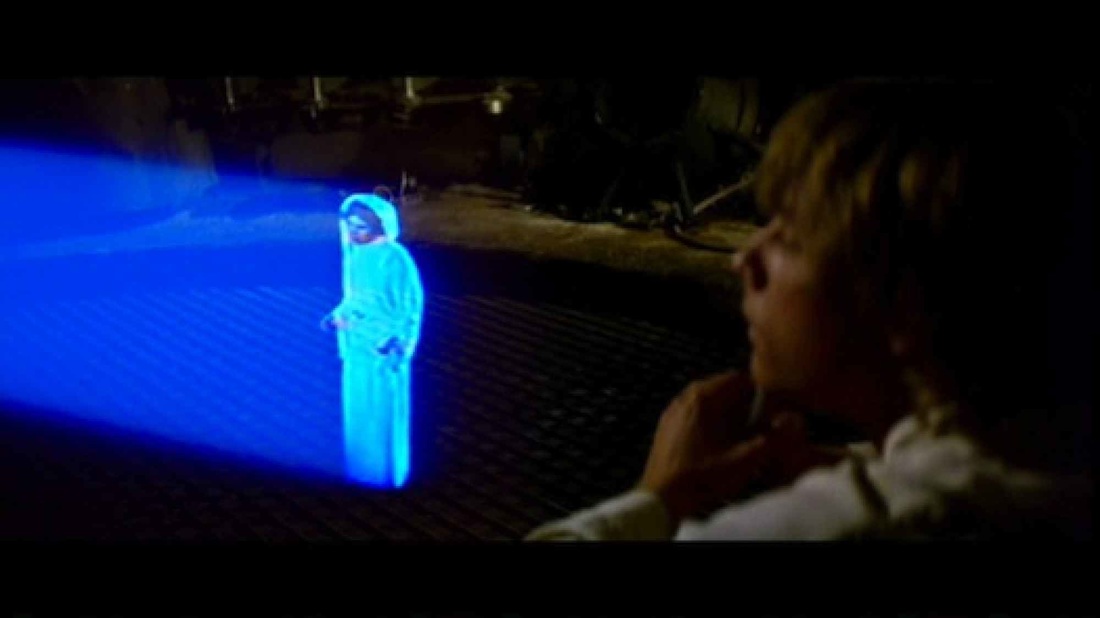

Dictionaries say one thing, but popular discourse says much more. From its birth as a collage of post-WWII optical sciences through the 1970s, holography was an evolving but fairly easily defined practice. Its products were called holograms — photo-like film images that delivered a more three-dimensional view of the subject. Then "Star Wars" happened. Black lives matter, yes. But what about black holograms?

The criminalization of black bodies apparently extends to their digital form, as well. This important lesson came to us via Chicago rapper Chief Keef, who a couple of weeks ago attempted to perform in concert as a hologram simulation; his digital body, however, was powered down and prevented from performing in the same manner as his physical body. It’s a weird case of police overreach and an interesting example of how culture is still trying to get its collective head around the meanings of hologram simulations. Perfume is a Japanese techo-pop group, a trio of women cranked out of a Hiroshima idol-singer mill nearly 15 years ago; last week they at last made their SXSW debut, after touring the United States for the first time only last year. Their performance — an eye-popping, digitally mashed-up overload of projection-mapped spectacle — offers exciting new ways to consider the negotiations between digital and live bodies on stage.

SXSW has supported talent from Japan for most of its run, despite often pigeonholing it in the single Japan Nite showcase — which observed its 20th anniversary this year (I had the fortune of being present for the first back in ’96, featuring the great Lolita No. 18). But as bands from Japan have upped their cultural cachet here, bigger acts have spilled over into the festival’s other venues and showcases. Perfume’s set last week — sandwiched at the end of the festival's Interactive portion and the beginning of its bedrock music week — certainly turned some heads. |

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed