|

Raffi Kryszek, of PROTO Hologram, and myself before the panel at SDCC22. What a great time hosting a panel at Comic-Con in San Diego on Friday! A sizable crowd joined us for "From Scifi Imaginary to Tech Reality: The New Science of Holograms" — and, wow, did they ask superlative, knowledgeable questions! Panelists were myself and Raffi Kryszek, the principal hardware architect for the PROTO Hologram company in Los Angeles. (Tara Knight from Colorado U's Critical Media Studies program was unable to make it.)  I finally got the chance to show off one of the only vintage comic books I possess: a 1978 one-off called Holo-Man, about a doctor zapped by high energy in a holographic matrix, which grants him superpowers (projecting illusions, time travel, invisibility). We parsed the various ways holograms have remained ubiquitous throughout science-fiction narratives, evolving the imaginary of digitally projected matter and characters. Then Raffi discussed the exciting work being done at PROTO to actualize that imaginary — creating life-size, photo-real 3D simulations of people through its unique "hologram" technologies. He even clued us into the next new model (desktop-sized!). Good stuff and good fun! Thanks to the Comic-Con folks for having us!

0 Comments

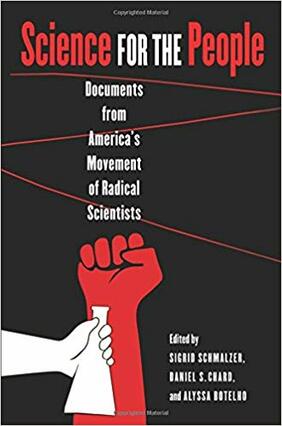

Science for the People was an organization of scientists and science workers who banded together around the turn of the ’70s to express concerns about the commercialization, industrialization, and militarization of science. The group raised awareness of a multitude of issues, organized and balanced public debates (which sometimes included disrupting establishment conferences), and published a spiffy magazine for nearly a decade. Worried about how science was being used against people, SftP advocated for. In 2014, a conference was organized at UMass-Amherst to examine the group’s legacy. At the close of the event, several attending students and scholars from across the country met to discuss ways to continue the examination, even ways to revive and evolve the mission of SftP. I was fortunate to be among this group, and the result of our decision has finally been realized in a new book: Science for the People: Documents From America’s Movement of Radical Scientists, now available. Attending San Diego’s famous annual Comic Con is a breeze — when you’re an STS grad student, at least. The lines for the Netflix trailers and movie sneak-peeks and TV cast conversations? Long, like crazy-long. The lines for the science panels? What lines?

My two most productive research interests seem quite different. My current dissertation project investigates the cultural histories and spatial embodiment of holograms and hologram simulations. In my copious free time (cough, sputter), I also maintain a course of study that began well before my grad-school adventure; as a journalist, both in Tulsa, Okla., and at the Chicago Sun-Times, I wrote a great deal about folksinger Woody Guthrie and the revival of his legacy within his home state, and now as a scholar I continue examining the ol' cuss and his peculiar communication strategies. One interest is old, analog, and sepia-toned; the other is shiny, digital, and futuristic.

But — as I explained in my presentation this weekend at the Woody Guthrie Symposium, hosted jointly by The University of Tulsa and the Woody Guthrie Center — there's actually a bit of Venn-diagram shade between the two. What interests me about these emerging "hologram" technologies, especially uses of the tech in pop-music performance contexts, is how the digitally projected characters achieve some semblance of believability, how their creators manage to craft a successful performing persona, and whether these simulations can claim something like Benjamin's "aura" or even Bazin's "fingerprint." This is not far removed, I'd say, from the process human performers go through in crafting their own performing personas — which is what I claim Woody did during his two years on L.A. radio beginning in 1937, as a direct result of his encounter with the new mass medium and its delayed feedback channels. Such is the basis of my paper on the subject, and my talk this weekend. No one, to my knowledge, yet has proposed that Woody be among the legions of dead musicians resurrected in hologram form. This sounds like both a terrific idea (he'd probably love it) and a dreadful idea. Who knows? (photo by @notalyce) It's conference month for me — this time to Theorizing the Web, last weekend in New York City. Specifically, fitting the group's un-conference feel, in a warehouse in Williamsburg.

TtW is a gathering of ridiculously smart people working on projects related to network analysis, social media, human-computer interaction, and all manner of online and infrastructure theory. What an invigorating weekend at UMass-Amherst for the one-off conference about Science for the People! Organized by Sigrid Schmalzer and her comrades at the university's enviable Social Thought & Political Economy program, the two-day gathering assembled nearly 200 people — most of them former members of Science for the People, and many of them enjoying the reunion with colleagues and cohorts — to discuss the legacies and lasting impacts of the group's resistance, publications, and educational efforts.

Founded in 1969, SftP became a diverse national network of scientists commonly concerned about the increasing militarization and corporatization of scientific research. Through organized confrontations at established science conferences, various street-level social projects, and an impressive, eponymous bimonthly magazine that published for 15 years (now neatly archived online), SftP sounded early alarms about issues ranging from drones (as early as 1973) and computer surveillance to the commercialization of biotechnologies and genetic manipulation. Early in the conference, the consensus was clear: these issues have grown only more urgent, and much work remains. |

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed