|

In many of my media-studies courses, we usually begin by underlining the idea that all communication is mediated. Some students initially resist this. They see conversation and face-to-face interactions as direct, unmanaged, unmediated — communing rather than communicating. Once we get going, though, they learn to see the mediation in play even here: gestures and visuals, language itself, social forces, and the very spaces of interaction. There is no mind meld. There’s always a mediator.

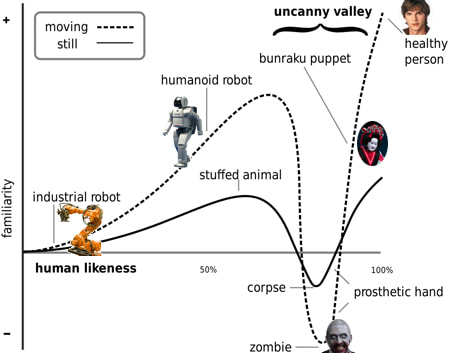

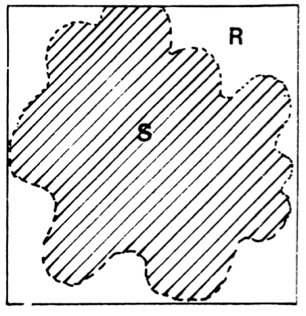

Many emerging media, however, would like their users to think like those hesitant students — to experience the pre-programmed interactions of their technologies as unmediated, to ignore the inherent and carefully managed structure of the encounter, to assume that the communication is direct and free of outside influence. Thus the rapid development of digital channels that seem more “natural.” ChatGPT and other AI systems free users from having to learn a particular communication code; instead of mastering the art of the Boolean query in order to maximize Google results, ChatGPT speaks our language, as it were. Ask it a complete, “normal” question, and receive an almost human response rather than formatted results. Siri, Alexa, and other voice assistants create seemingly interpersonal encounters via natural language, as if we’re conversing easily with another subject rather than interrogating a bot. Only when the systems make mistakes do they become more visible in the exchange and remind us that, oh right, I’m talking to a machine. To further understand this kind of situation — and especially in the context of my investigations related to digital holograms, which only succeed as communication if their mediating apparatus is similarly hidden from the user’s experience — it may be useful to adopt a theory that was coined in the context of literature and art and adapt it within media studies: demediation.

0 Comments

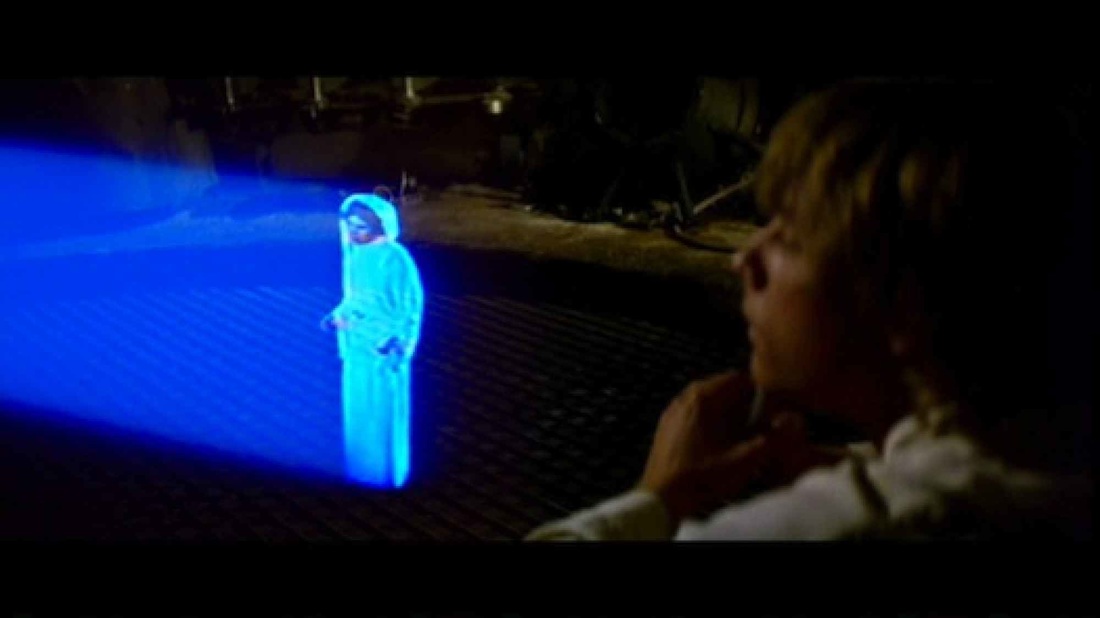

In the early 1990s, folk-rocker John Wesley Harding released one of the best B-sides around: “When the Beatles Hit America.” A lengthy narrative about a dreamed-up Fab Four reunion, it envisions both cultural and technological contexts for a new Beatles event — and this is back when only one of them was dead. In Harding’s epic ballad, the Beatles are going to reunite on stage, all “due to a miracle marketing strategy / beyond the realms of reasonable possibility.” The lyrics realistically dramatize the build-up (securing the film rights, sponsorships, talk show scheduling, etc.) and then inject a bit of scifi to make it happen (the manager of the new Beatles is “made up of cloned parts of Col. Tom Parker and Col. Sanders”). Ringo won’t actually play, though, because he’s been replaced by a more accurate drum machine; he’s “disappointed to find that no one / needs him anymore except for the vibe.” Lennon, meanwhile, is substituted with a life-size cardboard cutout, and then — per today’s news, in a way — he speaks to the press, sounding suspiciously like some old recordings: John, who was never the quiet one makes all his press contributions from his old songs -- in tune, in time, and with the backing track behind him And when they ask him how it’s been in the studio, he says, “It’s been a hard day’s night” And no one understands him, but he always was the cryptic one … Funny stuff, but now prescient. Today marks the release of the Beatles’ latest — and allegedly last — technologically resurrected cast-off, a “new” old song called “Now and Then” that features the two living members and the two dead ones reunited in eerily perfect harmony and time. As a scholar who studies the uncanny properties of media and its inherent constructions of liminal spaces between life and death, well, I have some initial thoughts. A new journal article of mine is now published: "Rock and Roll Will Never Die: Holograms and the Spectrality of Performance" in the spring issue of Spectator, the film-studies journal at USC. The work extends a conference presentation I gave at USC's First Forum in 2021. The abstract: In 2012, the rapper Tupac Shakur performed in the top slot at a major music festival — an event only notable because he had died 16 years earlier. The performance was made possible by a 21st-century digital upgrade of a 19th-century stage illusion called Pepper’s Ghost, and it ushered in a trend of creating and presenting similar “hologram” performances of posthumous pop stars. This article offers an explanation of what is seen in such a performance, examining the simulation of 3D video imagery designed to veil its mediation in order for its subject to appear unmediated, present, and “real.” Ultimately, I claim that these illusions are contemporary séances — a revival of historically spiritualist practices but one in which what is conjured is actually the deceased’s previously existing performing persona, as the concept has been extended by Philip Auslander. This cultural entity (distinct from the body and able to outlive it) is offered a new embodiment within a media system that restores the immaterial entity to the material space of the stage — a context previously off limits to the dead performer. Read the article here!

I've written before here about David Gunkel's research and thoughts on the social rights of robots. He's now summed up the many arguments for and against — and contributed his own, based on the philosophy of Levinas — in a new book, Robot Rights, from MIT Press. I jumped at the chance to review it, and it's finally published online.

And, hey, Gunkel referred to my review as "positively brilliant"! “What year is this?” It was an extraordinary last line for a wide variety of reasons. Aside from those relevant to the narrative, it’s a question I hear asked often of pop cultural events. Like: “Nintendo is releasing a mini NES? What year is this?” “Billy Idol is opening for Morrissey? What year is this?” Even and maybe especially: “A new season of Twin Peaks? What year is this?” Sunday night’s anticipated finale of Twin Peaks: The Return capped an extraordinary run of television. That certain chunks of this 18-hour avant-garde odyssey are out there in the stream now — for everyday channel surfers to just stumble upon — blows my happy mind. This post is not a review of the show — there are plenty of good ones out there now — but just a quick knocking together of some thoughts about the series’ intriguing engagement with representational technologies and death. (And it does contain spoilers!) I think I possess the very opposite of a macabre personality, but I’m thinking a lot today — in grave detail, shall we say — about my father’s corpse.  This month saw publication of The Oxford Handbook of Music & Virtuality, containing my chapter, "Hatsune Miku, 2.0Pac and Beyond: Rewinding and Fast-forwarding the Virtual Pop Star." In it, I survey a history of virtuality in pop music stars, from the Chipmunks and the Archies up to Gorillaz and Dethklok — many of the non-corporeal, animated characters that presaged current virtual pop stars like Hastune Miku and the Tupac resurrection. What is a hologram?

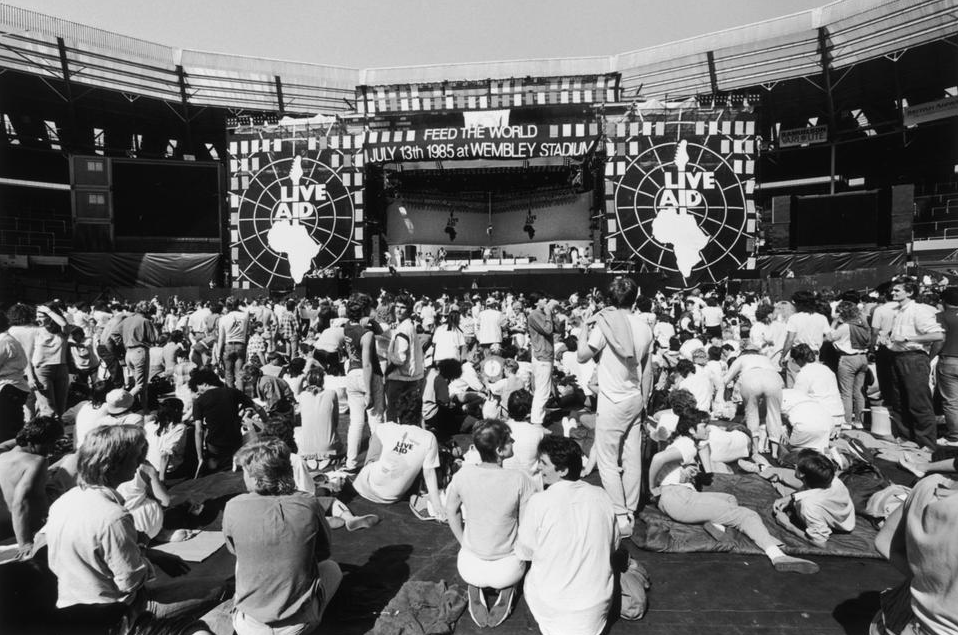

Dictionaries say one thing, but popular discourse says much more. From its birth as a collage of post-WWII optical sciences through the 1970s, holography was an evolving but fairly easily defined practice. Its products were called holograms — photo-like film images that delivered a more three-dimensional view of the subject. Then "Star Wars" happened. This week marks the 30th anniversary of Live Aid. Memory flashes I’m still able to conjure from my aging brain: Paul Young’s flouncy pirate cuffs, the poetic irony of Geldof’s mic failing during his own set, Elvis Costello’s classy choice of "an old northern English folk song," the Pretenders’ playing surprisingly laid-back, of course U2’s career-making set and Queen’s delivery of the world’s quintessential arena-rock performance. Political opinions aside, it was an unequaled day of, let’s say, musical performativity.

The DVD set of the concerts bears a postmark-like stamp that reads, “July 13, 1985: The day the music changed the world.” Thirty years have allowed for much evaluation of nearly all the changes wrought (not all for the better; read this excellent piece about Live Aid’s “corrosive legacy”). What it did change — drawing from research I conducted a few years ago into protest music (or the lack thereof) at Occupy Wall Street events — was the common conception of popular musical protest practice, resituating it from the open street to the ticketed arena, as well as the establishment of celebrity at the very core of such practices. There's an oft-cited quotation within the circles of popular music. It goes like this: "Writing about music is like dancing about architecture." It's a succinct summation of the challenge of music criticism — of experiencing the ineffable magic of any art and then using mere words to pin down all that smoke. Throughout my 20 years getting paid to do just that, I recognized the futility of the activity (while counting my lucky stars).

The quote — attributed to a wide variety of sources, though it was most likely a Martin Mull original, according to the fearless and tireless Quote Investigator — usually is bandied about by musicians (commonly by those who have been on the receiving end of some sharp criticism) with the intent of belittling music critics. They wield the statement in order to point out how worthless is the critical pursuit, how beneath their attention. They could be right. But I'm newly involved in plumbing the depths of performance studies, and it's lead to a not-small revelation about that quotation's very metaphor. (photo by @notalyce) It's conference month for me — this time to Theorizing the Web, last weekend in New York City. Specifically, fitting the group's un-conference feel, in a warehouse in Williamsburg.

TtW is a gathering of ridiculously smart people working on projects related to network analysis, social media, human-computer interaction, and all manner of online and infrastructure theory. Life is great like this: I spent an afternoon this week unpacking the remainder of my library (delayed, as often happens, months after moving in), and basking in the intense comfort of having treasured volumes once again within reach; then, I sat down with a well-earned cocktail and opened Illuminations, a collection of Walter Benjamin essays recently added to my to-read shelf — and what to my wondering eyes should appear but the anthology’s first selection: “Unpacking My Library.”

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi is the patron saint of finals weeks. The psyche prof developed the concept of the “flow” state. (Watch his TED about it.) You know it as being “in the zone” — that state of concentration where you become so deeply involved in an activity that you lose time. Csikszentmihalyi described it as being “completely involved in an activity for its own sake. The ego falls away. Time flies.” Flow is essentially an intense but positive and creative feeling of presence (Heeter, 2003). If, like me, you’re writing papers right now, flow-ing is where you want to be.

For this writer, background music has become essential to reining in my limbic system and achieving something like Csikszentmihalyi’s flow state. To that end, I’ve found a few resources pretty indispensable this year. My early days as a rock scribe pre-dated most indoor smoking bans. I used to keep a separate wardrobe of club clothes — stuff I didn’t mind getting infused with ashtray aromas, since even repeated tumbles in the wash didn’t remove the smell completely. I stopped smoking at the dawn of the ’90s, but my transition was made easier by working within the clubs’ secondhand cloud. When I was a critic again in Chicago the last few years, it was always strange to be seeing a band clearly and exiting the club not reeking of cigarettes.

Nathan Jurgenson (he of the smart arguments against dualisms of online-offline, virtual-real, live-mediatized) recently tweeted: “lol-op-ed idea: ‘the rock club’s cigarette-haze has been replaced by screens & now we’re all coughing in the digitality.’” Funny, but true — and perhaps a useful metaphor: the eversion of cyberspace is an exhalation, a long stream of bits billowing into our various environments, from the backrooms of clubs to the backseats of cabs. The first time I saw Hatsune Miku in concert, I started scribbling notes. “It’s Rei Toei!!” was the first thing I wrote. That was the 2011 Live in Sapporo show, simulcast to movie theaters in nine U.S. cities. Last weekend, celebrating the Japanese digital idol’s sixth birthday (well, her sixth 16th birthday…), Miku’s Magical Mirai concert was broadcast on delay to just two cities here (LA and NYC) — but the show was a remarkable improvement and a blockbuster performance all around. I couldn’t help but scribble more notes, including this possibly more telling one as Miku appeared with a guitar: “Transformation to Madonna complete.”

|

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed