|

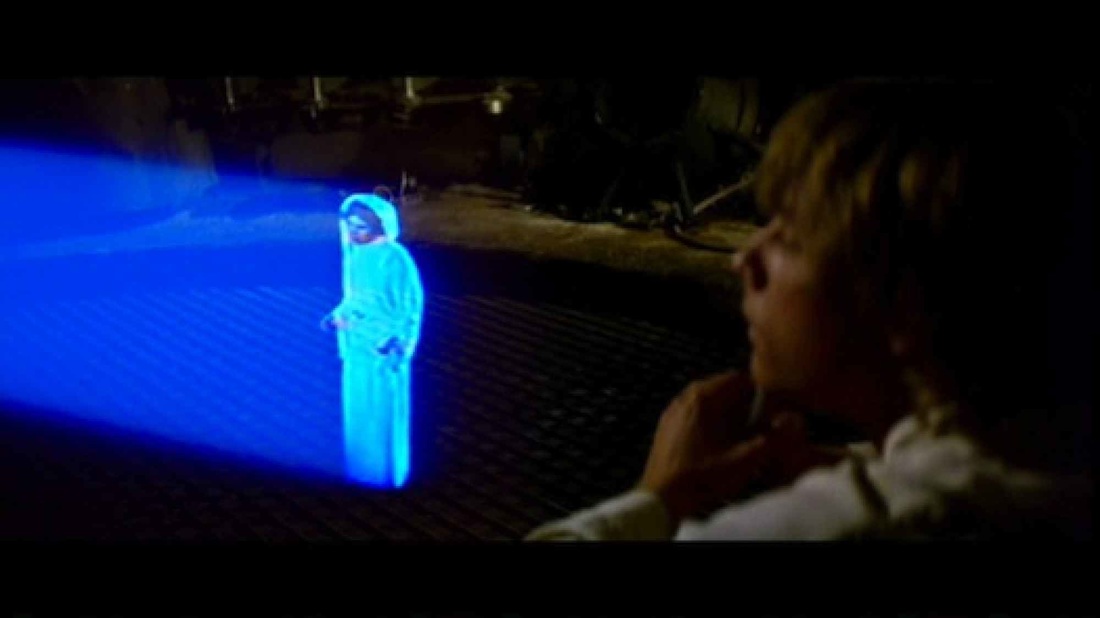

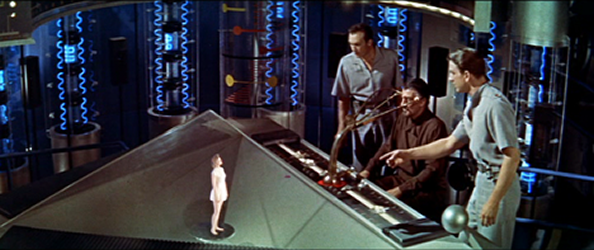

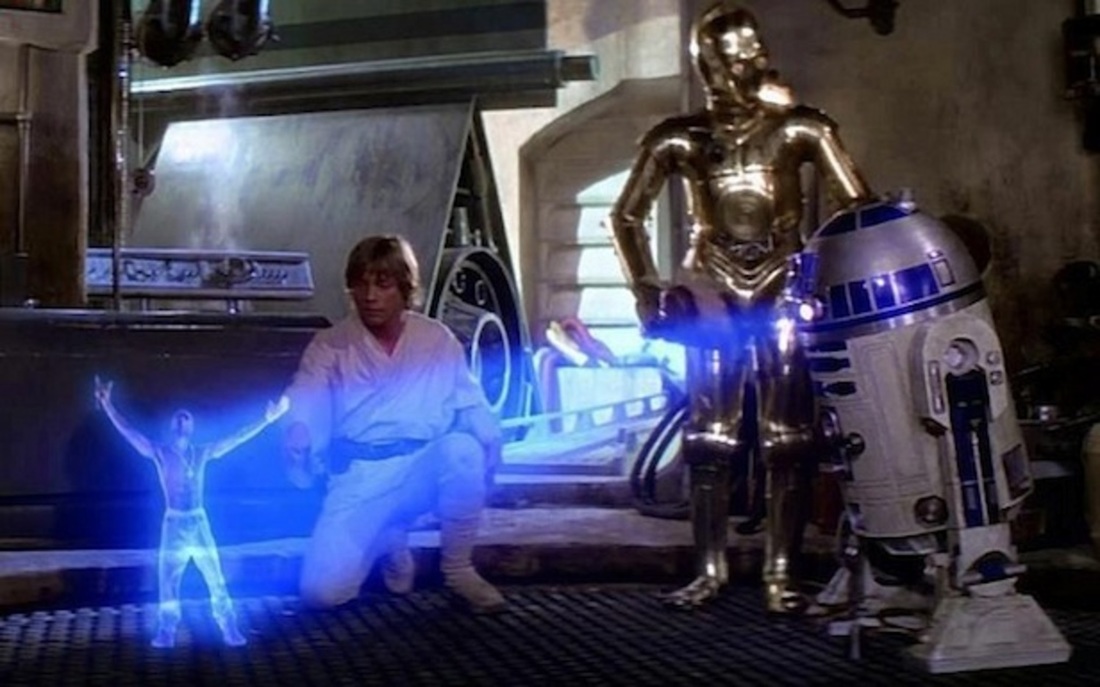

What is a hologram? Dictionaries say one thing, but popular discourse says much more. From its birth as a collage of post-WWII optical sciences through the 1970s, holography was an evolving but fairly easily defined practice. Its products were called holograms — photo-like film images that delivered a more three-dimensional view of the subject. Then "Star Wars" happened. A post-production visual effect in the first “Star Wars” movie — the illusion of a 3D, asynchronous video-mail message from Princess Leia as played back by R2D2 — marked a pivot point in the lengthy historical project of the technological transplane image. I’m currently at work on a series of papers linking the theoretical concepts of virtuality and tele/presence, and tracing a genealogy of humanity’s technological efforts to manifest presence virtually (“holograms” are far older than holography!), but here — since a sizable chunk of contemporary humanity, including myself, is blabbering this week about the newest addition to the “Star Wars” transmedia narrative — I’m interested in playing through a bit of etymology. When I say or write the word “hologram,” in most contexts the colloquial understanding is very Leia-like — a three-dimensional image digitally projected and cohering in real physical space, with no goggles or even a screen required to view the image-object. This concept has nearly nothing to do with the actual science of holography — which uses coherent light to capture and reproduce diffraction patterns within a film — and both the holographers and the artists I’ve interviewed rush to make the distinction, despite ultimately and wearily resigning themselves to the dominant discourse. “A lot of people call it holography,” performance artist and hologram-simulation designer Michel Lemieux, of Montreal’s 4D Art, told me, echoing a common refrain. “At the beginning, 20 years ago, I was kind of always saying, ‘No, no, it’s not holography.’ And then I said to myself, ‘You know, if you want to call it holography, there’s no problem.’ We’ve seen it in ‘Star Wars.’ Yes, it’s not technically holography, it’s an illusion.’” “Star Wars,” indeed, contributed significantly to the transformation of what a “hologram” is and means. No one in the original movie utters the word “hologram,” even in reference to R2D2’s primitive combination of a personal-presence device and Skype. George Lucas’ original story sketch for “The Star Wars: Adventures of the Starkiller” contained an idea of this kind of mediated message, but it was referred to merely as a “projection,” only becoming a “hologram” in an early draft and described in terms that immediately merged the multi-colored appearance of actual transmission holograms and the unsteady aspects of broadcast or projected visual media: Artoo makes a few electronic beeps and whistles; then after a little static, a small (two foot) 3-D hologram of Deak is projected from the face of the robot. The image is a rainbow of color as it flickers and jiggles in the desert wasteland As the script developed, the image-object became a “three-dimensional hologram of Leia Organa, the Rebel Senator” and had shrunk from two feet tall down to 15 inches and then, in the shooting script, 12 inches. This is an imagery markedly different from actual holography. First, the image is a projection, unlike optical holography, as well as an animated one. Second, it is projected from a computer, which marries the concept of 3D image projection to digital technologies in a manner that will be difficult to divorce from this point forward. Third, the image is a communication, a message delivered in the most cumbersome and asynchronous means conceivable: use the robot to record your message, store your message in the robot, then send the robot traveling through the galaxy in hopes it will serendipitously stumble upon the remote address of an elderly desert hermit. When, in 1949 (as relayed in Sean Johnston's excellent history of holography, Gordon Rogers sent a brief letter to fellow holographer Gabor — a brief bit of text sketched out as an actual hologram, and measuring only 6mm across — he added a postscript: “Holography is a very slow means of communication!” No kidding. Still, the Lucas concept of a “hologram” — a composite of antecedents from throughout pulp sci-fi, from “Forbidden Planet” (1956, above) to “Logan’s Run” (just a year before “Star Wars” and using actual multiplex holograms for the climactic and Oscar-winning visual effect) — seemed to realize something desired from just such a technological project. The next two decades of sci-fi texts, primarily visual episodes and films, supercharged the evolution of the concept by exploring myriad ways in which humans might interact with computers via screenless, 3D-projected displays or, importantly, interact with absent people and objects via 3D-mediated presence technologies. From “Minority Report” to the new series “The Expanse,” characters compute without keyboards and move through digital content without mice. “Star Trek: The Next Generation” created the virtual playpen of the holodeck, while “Star Trek: Voyager” crafted the compelling character of the holo-doctor, including important stories about holodeck confinement limited full human interaction and experience. The “Star Wars” universe expanded to include refined holo-communiqués in nearly every iteration. Even the slapstick of a sitcom like “Red Dwarf” ably develops the idea of 3D-holo HCI and its importance to certain aspects of human psychology. What had been an actual technology, a hologram, transformed into a “hologram” — an imaginary medium precisely as Kluitenberg has defined. Within the pop-cult narratives, we have been able to explore what we might want from such technologies, should they someday exist. These narratives “indicate a desire or a premonition in many of us to see this kind of technology brought to life,” said three researchers working on just such a project. And there are many such researchers. University and commercial labs around the world labor on similar projects of somehow projecting a Leia-like 3D image into mid-air. The Leia meme is reproduced in headlines reporting on research — “In Search of the Princess Leia Effect,” “MIT: Princess Leia Hologram ‘Within a Year,’” “Princess Leia hologram could become reality” — as well as within the research itself, including conference-catnip titles such as “How Feasible Are ‘Star Wars’ Mid-air Displays?” One of the companies working to solve the riddle of volumetric display is even called Leia, Inc. Most reports are realistic about the fact that projecting a coherent 3D image into mid-air remains an impossibility, that “such applications are still science fiction.” Holography pioneer Stephen A. Benton minced no words to this effect a few years after “Star Wars” had set the idea aflame: R2-D2’s projection of Princess Leia’s spatial image (and similar projections in ‘The Empire Strikes Back’) has stuck in the minds of millions of people who ought to know better. Photons do not yet turn around in mid-air, as they would have to for such a result But even Benton said “yet,” and the refrain of this new hope resounds even in research that refers to the realization of Leia-like volumetric projections as "the ‘Holy Grail’ for 3-D display." Meanwhile, as we await the digital apparition of St. Leia Organa, a new performing hologram is promised almost weekly. In the wake of the groundbreaking Tupac hologram (itself an Americanization of performing-presence tech utilized earlier for concert performances by Hatsune Miku — who will herself tour the United States in the new year), companies like Hologram USA seem committed to resurrect the dead and keep them earning. That group has announced hologram-simulation performances, touring or otherwise, by musical figures from Billie Holiday to Tammy Wynette and even comedians Andy Kaufman and Redd Foxx. However, given this popular understanding of what a “hologram” is or could be, I haven’t found a dictionary that provides a more current definition. The OED's entry for “hologram” classifies the term as a physics concept and provides the foundational, technical definition involving light diffraction and coherent-light pattern construction. It provides historical citations of the term, beginning in 1949 with a paper by Dennis Gabor, who coined the term in this context. The most recent citation is from 1971. The same is true for OED’s “holography” entry. Common-use dictionaries offer only the technical definition, too. Dictionary.com does so with almost seems a lovely irony: after providing the technical definition, at the bottom of its “hologram” page are three aggregated current-usage citations, “Examples from the Web for ‘hologram,’” featuring headlines about the Tupac and Michael Jackson hologram simulations, which make little sense in juxtaposition to the sole definition above relating to laser-light diffractions. Below another purely technical definition of “hologram,” merriam-webster.com's entry features comments from the site’s users, more than half of which discuss holograms in as-yet-undefined contexts both old and new, including, “a life size hologram of a lady making an announcement at one of the U.S. airports.” Even a user-generated compendium of actively colloquial and slang terms fails to account for a single definition of “hologram” in the context of its current and widespread usage; urbandictionary.com features one technical definition plus two amusing slang applications: “a person who … contributes absolutely nothing to a conversation and has no personality whatsoever / Wow, you were being such a hologram I didn’t even notice you were there” and the most popular offering, as voted by the site’s users, “Any bittie who the normal man would wish is unreal or fake, due to actions that make the girl a joke / That girl hooked up with a D-Chi, now she is at hologram status.” It’s notable that both of these user definitions — which each deploy the term to transform people into illusory or almost-invisible objects — pre-date the heralded appearance of the Tupac hologram by five years. The current usage and understanding of "hologram" is being defined by the technology's developers. Microsoft's emerging HoloLens device offers interactive 3D visuals as well as the appearance of them being situated within real physical space, and the entire discourse of this new tech rests on the current usage of "hologram" to label the imagery. Microsoft has even offered up a definition of "hologram," with some interesting ontological aspects: A hologram is an object like any other object in the real world, with only one difference: instead of being made of physical matter, a hologram is made entirely of light. Holographic objects can be viewed from different angles and distances, just like physical objects, but they do not offer any physical resistance when touched or pushed because they don’t have any mass. Holograms can be two-dimensional, like a piece of paper or a TV screen, or they can be three-dimensional, just like other physical objects in your real world. So while the Oxford dictionary added “awesomesauce,” “cat café,” and “manspreading” to its lexicon this year, “hologram” remains alarmingly obsolete in the context of the existing media ecology. This week, no doubt, “The Force Awakens” will further the concept even more — I’ve heard the new film contains a hologram communication-projection that’s three stories tall! — while Hologram USA announces the preparation of yet another performer resurrected as a touring hologram, this time R&B singer Jackie Wilson.

Indeed, what is a “hologram”? Help us, OED, you’re our only hope!

1 Comment

Virtual On

12/10/2020 08:18:57 am

Thanks for sharing very informative data regarding the definition of hologram.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed