|

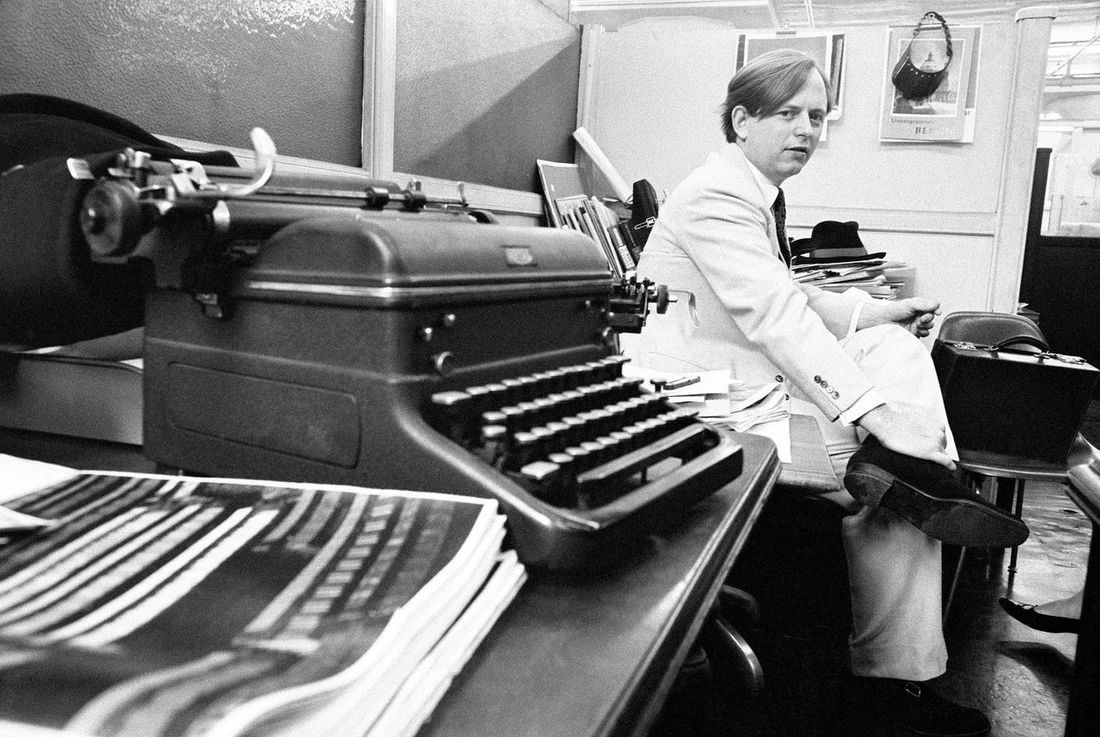

Early in their experience, journalists — most of them, I believe, probably naively — often experience something of a reckoning. After some time assembling different combinations of the five w’s (who, what, where, when, and why) and sometimes the extra h (how), newspaper reporters realize that much of their work is not writing at all, not in any literary sense. They begin “trying to understand why the conventional newspaper story … fail[s] to capture the essential truth of the experience.” Because when you’re on a beat, you’re a short-order cook, slingin’ hash. There may be eight million stories in the naked city, but a cops reporter isn’t weaving narratives as often as she’s simply stringing together just the facts, man, and in less than 300 words, please. This epiphany can be positive or negative. It can lead to a change of career or a visit to the editor’s office to ask not for a monetary raise but an elevation in scope, opportunities with a bit more depth of narrative and space on the page. In the mid-20th century, a bevy of writers experienced a similar revelation at around the same time. Parallel to challenges to other social mores, these writers sought to break down and break out of the rigid AP pyramid standard for story structure. Novels had so many techniques, journalism so few: why not cross-pollinate? New and reimagined magazines, from Esquire to Rolling Stone, welcomed the experimentation. History classified their collective efforts as the New Journalism — and Tom Wolfe was the best of the lot.

2 Comments

|

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed