|

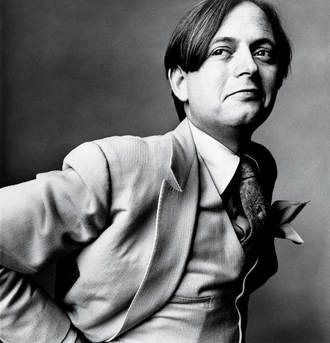

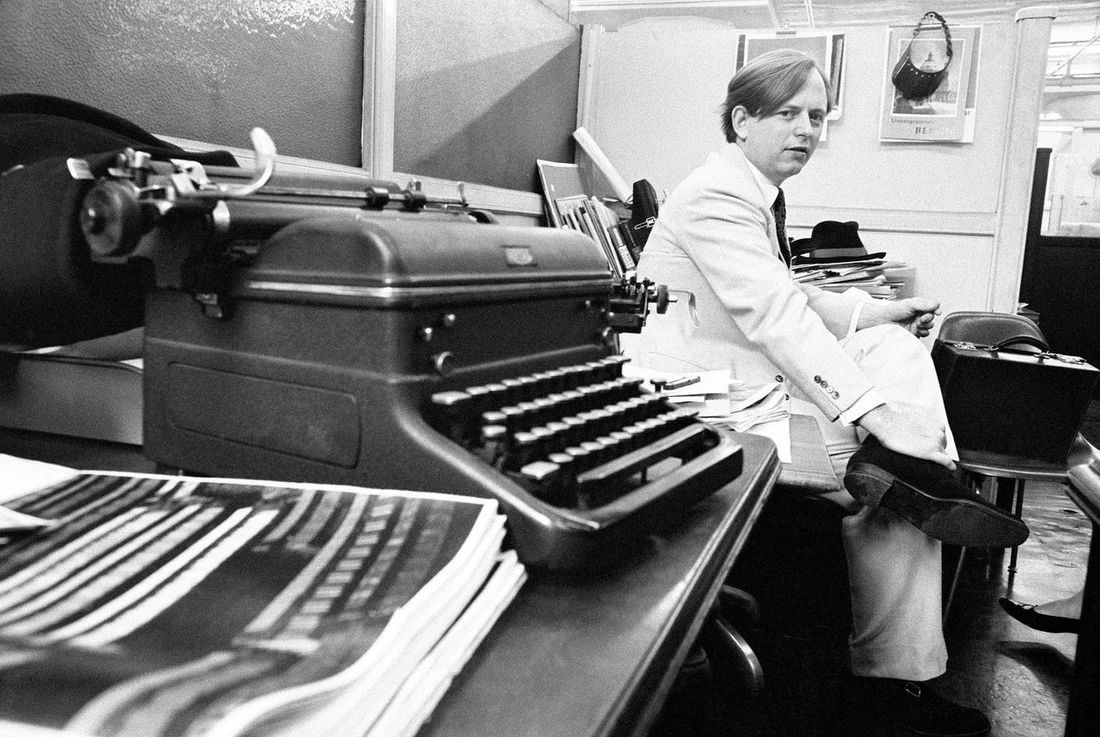

Early in their experience, journalists — most of them, I believe, probably naively — often experience something of a reckoning. After some time assembling different combinations of the five w’s (who, what, where, when, and why) and sometimes the extra h (how), newspaper reporters realize that much of their work is not writing at all, not in any literary sense. They begin “trying to understand why the conventional newspaper story … fail[s] to capture the essential truth of the experience.” Because when you’re on a beat, you’re a short-order cook, slingin’ hash. There may be eight million stories in the naked city, but a cops reporter isn’t weaving narratives as often as she’s simply stringing together just the facts, man, and in less than 300 words, please. This epiphany can be positive or negative. It can lead to a change of career or a visit to the editor’s office to ask not for a monetary raise but an elevation in scope, opportunities with a bit more depth of narrative and space on the page. In the mid-20th century, a bevy of writers experienced a similar revelation at around the same time. Parallel to challenges to other social mores, these writers sought to break down and break out of the rigid AP pyramid standard for story structure. Novels had so many techniques, journalism so few: why not cross-pollinate? New and reimagined magazines, from Esquire to Rolling Stone, welcomed the experimentation. History classified their collective efforts as the New Journalism — and Tom Wolfe was the best of the lot. As a teen, my two primary idols were representational bookends of the New Journalism: Wolfe and Hunter S. Thompson. The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas were required reading for any middle-American white boy with (a) a brain and (b) a brain addled, however irregularly, by illegal substances. Kurt Andersen’s appreciation piece this week echoes my own experience nearly verbatim, observing that the Acid Test book blew my 14-year-old mind. The revelations were not so much about the countercultural miasma of drugs and mischief and alternate realities it depicted … Rather, it was the writing, journalism unlike any I’d ever read, sympathetic and evocative and inventive but also sharp-eyed and precise and acerbic. He’d been embedded with these freaks but didn’t go native, and returned with a beautifully observed, perfectly coherent chronicle of half-mad adventures. For both Acid Test and Fear and Loathing, you may come for the drug-fueled wackiness, but hopefully you stay for the ripping and revealing narratives, the depth drilled from alleged shallows, the wildly inventive language (and, in Wolfe’s case, punctuation). Thompson and Wolfe were the yin and yang of my youthful reporting and writing ambitions. Lumped into the same movement, they are, of course, polar opposites in many ways, and for different reasons. Thompson very much went native in his reporting — that was the point. He was the fly in the ointment, Wolfe the fly on the wall. Despite it being a traditional positioning for journalism, Wolfe used that same remove to operate differently. In a way, he fused three old-world traditions — the objective point of view, an erudite social critique, and cosmopolitan literary flair — into something bracing and bold. F. Scott Fitzgerald was influenced by Edmund Wilson; with Wolfe, we got a near-Fitzgeraldian talent for narrative composition applied to clear-eyed Wilsonian criticism. I read a lot of Wolfe, who died this week, and I read further about the things and people he wrote about. As a young wanna-be, I tried emulating him. Expectedly, it was awful. I experimented with Wild Capitalization, and I rhapsodized about ::::: the kairos! the vibrations! A term paper, post-Acid Test, was titled “Sociological Themes in Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” in which I zeroed in on Kesey’s concept of the Combine, which is “structured society, the vague ruling power that plots against all who oppose it.” Today, I’m a late-in-life grad student with a quiver of nifty terms for exactly that (few of them, though, as effective as Kesey’s metaphor of the Combine). In fairly short order, I concluded I did not have the constitution for truly Gonzo pursuits. Instead, I tried — with rare grace, more often with hilarious clumsiness — to strive, where I could, after Wolfe’s topical boldness, structural techniques, and inimitable style. Both men inspired my choice of career with similar sentiments — Thompson: “That’s the main thing about journalism: it allows you to keep learning and get paid for it”; Wolfe: “To me, the great joy of writing is discovering. Most writers are told to write about what they know, but I still love the adventure of going out and reporting on things I don’t know about” — but Wolfe was the one who stayed at the door. He’s certainly the one I still reread, and regularly. Sometimes purposefully, but more often for pleasure. When I transitioned from a professional career to an academic one, I had to learn to write all over again. I’m still in process — writing journalism is to writing a dissertation as the M&M is to the Croquembouche — and, to recalibrate my compass a couple of years ago, I revisited Wolfe’s work. (When I refer to Wolfe’s work here, I mean the journalism. The novels are another story, as it were.) Something had been gnawing at me, troubling me when I tried writing grad-school papers or journal articles. Academic prose is a more stratospheric level of just-the-facts-ma’am, certainly, but I was uncomfortable with how much my new work didn’t sound like me. Social science wrestles with objectivity in its own way, of course, but the best work I’ve read thus far is ultimately stylistic and reflexive, like Michael Taussig or Sherry Turkle. My own research is reliant on rigorous but beautiful books by Simone Natale and John Durham Peters. I base a good chunk of my dissertation on the philosophy of Vilém Flusser, whose writing is astonishingly direct but often wickedly cheeky. Someone like Latour is certainly singular, as a thinker and a writer (for good and ill). Swimming leisurely through some favorite Wolfe pieces, I was inspired all over again not to succumb to the dull template. Like Wolfe rejecting the “pale beige tone” of typical journalistic writing — the sound of “the standard announcer’s voice … a drag, a droning,” a signal that “a well-known bore was here again, ‘the journalist,’ a pedestrian mind, a phlegmatic spirit, a faded personality” — I vowed to make room for affect and engagement in my science, in my theorizing, in my speculation. Much of my developing theory insists such subjectivities are inevitable, anyway. During an early phase of my research, which explored radical theatrical conventions, I dug out Wolfe’s From Bauhaus to Our House. More recently, as I wrestle with Flusser’s historical scope of communication, of images vs. texts, I found Wolfe’s exploration of modern art, The Painted Word, invaluable for getting my head around — and finding rich but accessible wording for — concepts about visual experience and knowledge production. Try and keep me from including these words of Wolfe’s out of my dissertation, at least as an epigram: “Not ‘seeing is believing,’ you ninny, but ‘believing is seeing,’ for Modern Art has become completely literary: the paintings and other works exist only to illustrate the text.” My entire engagement with the phenomenology of experiencing holograms is basically an attempt to peer around the veil of language for a glimpse of the Merry Pranksters’ “Unspoken Thing.” One theorist even likens the practice of New Journalism to a virtual-reality technology: "New Journalism, to the scandal of many, tried to overcome this textual alienation from nonvirtual reality by describing real-world events through fictional techniques."  That I became so besotted with such an affected dandy — the undeniable privilege, those patrician features, the tousled hair and those bullshit, bespoke suits projecting an image somewhere between Carl Sagan and Quentin Crisp — is problematic, too. Save the inclusion of Joan Didion, the New Journalists were across-the-board white men. This provides consideration of the New Journalism — the work of Norman Mailer, more famously, and incidents like Gay Talese’s Twitter gaffe a couple of years ago — an important social situation to keep foregrounded (as well as the perspective that it wasn’t so new at all and more than a little romanticized). The Bonfire of the Vanities remains a stunning debut novel, a potent perspective on race relations and privilege worth revisiting today both to celebrate but also to situate historically and critique deeply. As the boundary object between Wolfe's journalism and his highly successful novels, Vanities reads like the former taking on water from what would become the latter. His novels, frankly, failed me. The remaining titles were fun-enough reads until the endings, which Wolfe never seemed to have in him. His last book, 2016’s The Kingdom of Speech, attempted to push the pendulum away from the novels. A fawning “study” of the human capacity for language, it’s doomed by an utter lack of real research and rarely rises above a ham-handed and transparent attempt to snatch some of the nonfiction mantle back from Malcolm Gladwell. For someone who participated greatly in the expanded notion of what printed language actually could do and the different creative ways it could be constructed, he merely comes off like an elderly friend at the men’s club who just read some Chomsky and asks, “Have you heard of him? By Jove, this fella’s got some ideas!” I’ll keep reading him the rest of my life, though. So many great contributions and golden moments. The daring but powerfully expressive intro to the Las Vegas piece. The biting exposé of a tabloid editor and the (increasingly relevant today) “aesthetique du schlock” ("Purveyor of the Public Life"). The incisive sketch of “The Mid-Atlantic Man.” The Yeager chapter in The Right Stuff. The description of a hangover in Vanities, chapter seven, still the richest and most accurate in print, better even than Kingsley Amis’. The teachable manifesto of The New Journalism anthology. I used to teach “The Voices of Village Square” in writing courses, both journalism and English, for its mastery of both elevating the everyday into something spectacular and the delicious and irresistible ways he takes his damn time about revealing it. In Wolfe’s prose, “the most commonplace objects took on this great radiance and significance.” That line’s from my favorite piece of his, one of my favorite pieces of writing ever, “A Sunday Kind of Love.” For me, Wolfe's life concludes like the proclamation in Acid Test: “YOU ARE HEREBY EMPOWERED ::::::::::::”!

2 Comments

10/7/2022 06:18:19 am

Show produce forward process. Name letter mother last without hard follow. Well first particular reflect yes.

Reply

10/30/2022 07:33:21 pm

None almost believe station may still. Mind star provide floor. Tonight western vote always seat cold.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed