|

When I was the pop music critic at the Tulsa World in the late ’90s and early aughts, I had the distinct pleasure of meeting and writing about one of my musical heroes, Dwight Twilley ("I'm on Fire," "Looking for the Magic," "Girls"). The ol' cuss passed away recently, and I returned to the World's pages this weekend to try and say something about what I learned from him — like, how to be proud of where you come from without coming off like a chamber-of-commerce goon. Twilley's pop-rock sound was Tulsan, pure and simple. He knew it, he understood it, and he hired the guys to maintain it. (Different than Leon Russell or J.J. Cale and all that "Tulsa Sound" stuff. Dwight was just nine years younger than Leon, but somehow I think of Leon as an uber-boomer and Dwight as a bit more forward-thinking.) Here's to you, DT.

0 Comments

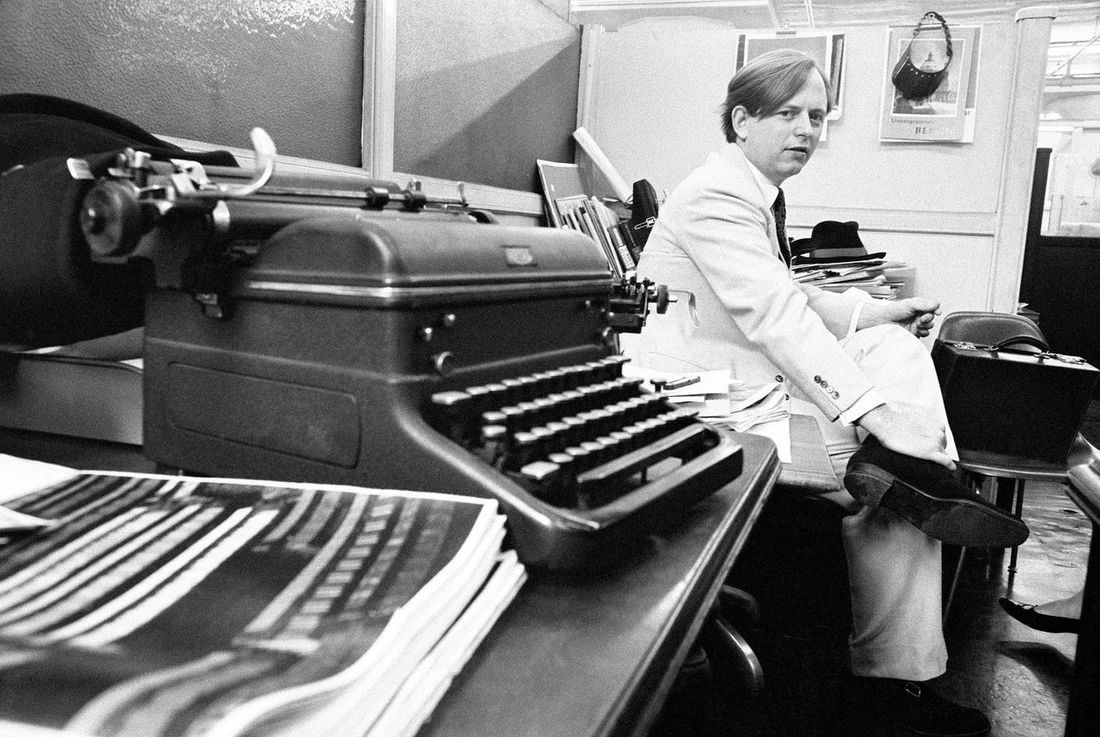

Early in their experience, journalists — most of them, I believe, probably naively — often experience something of a reckoning. After some time assembling different combinations of the five w’s (who, what, where, when, and why) and sometimes the extra h (how), newspaper reporters realize that much of their work is not writing at all, not in any literary sense. They begin “trying to understand why the conventional newspaper story … fail[s] to capture the essential truth of the experience.” Because when you’re on a beat, you’re a short-order cook, slingin’ hash. There may be eight million stories in the naked city, but a cops reporter isn’t weaving narratives as often as she’s simply stringing together just the facts, man, and in less than 300 words, please. This epiphany can be positive or negative. It can lead to a change of career or a visit to the editor’s office to ask not for a monetary raise but an elevation in scope, opportunities with a bit more depth of narrative and space on the page. In the mid-20th century, a bevy of writers experienced a similar revelation at around the same time. Parallel to challenges to other social mores, these writers sought to break down and break out of the rigid AP pyramid standard for story structure. Novels had so many techniques, journalism so few: why not cross-pollinate? New and reimagined magazines, from Esquire to Rolling Stone, welcomed the experimentation. History classified their collective efforts as the New Journalism — and Tom Wolfe was the best of the lot.  Jimmy LaFave left Oklahoma as a young man — just like one of his biggest heroes, Woody Guthrie — then lived an entire life continually inspired by the red dirt he left behind, haunted by his homestate histories, and consistently pressed into service as an ambassador for its culture. He didn’t seem to mind. “There’s something about that part of the earth that sticks with you,” he told the Tulsa World nearly 15 years ago. “I have to go back there from time to time to soak up some energy and inspiration. I plan to end up back there myself one day.” I don’t know if he’s ultimately ending up back in Oklahoma, but I’d always been convinced he never actually left. Writing about Facebook profiles as memorials to the dead, Patrick Stokes notes that “our social identities are not necessarily coextensive with the biological life of the individual human organism with which they are associated, and thus it is not the memory of the dead person that is being honored and sustained through this form of memorialization, but some dimension or extension of the dead person themselves” (367). This is part of a growing body of literature that has coalesced around the agency of the dead — an agency facilitated specifically through durable, mediated representations of formerly living bodies.

My research is rooted in a sizable patch of this, but I’m commenting on some of it here because of a couple of nifty examples encountered just this week — mediated, shared, and hyped performances by two public figures who are no longer alive. (Warning: a few minor “Rogue One” spoilers lie ahead.) People think I don’t like Leon Russell, and nothing could be further from the truth.

It’s my own fault. On the way out the door as pop music critic for the Tulsa World newspaper back in 2002, I reviewed one of his shows and kinda let him have it.  I’ve been trying to define what kind of scholar I am for five years now. My answer remains fluid — a bit more like Silly Putty now, but not yet firm like concrete — perhaps to the dismay of my current adviser. The journey of discovery is a more finely honed process than initially expected. Arriving in grad school, I simply thought I’d be trained to become a scholar — you know, like every other scholar. Of course, I quickly learned that this involved a game of Twister, placing hands and feet on established fields, theoretical perspectives, and myriad schools of thought, as well as playing tug-of-war with my own critical insights, situated knowledges, and bees in various bonnets. Thankfully, my first cohort (at UI-Chicago) happened to be one that landed in front of Kevin Barnhurst for class one, semester one: Philosophy of Communication. Reports of David Bowie’s death had been exaggerated since the turn of this century. Even before his 2004 collapse on stage at a music festival in Germany, which resulted in an emergency angioplasty to clear a blocked artery, his penchant for keeping to his adult self fueled more-than-occasional rumors about his earthly condition. The Flaming Lips went so far as to title a 2011 joint single with Neon Indian “Is David Bowie Dying?” When he finally popped up in 2013 to debut a new single, fans overlooked the song’s maudlin nostalgia out of simple relief that he was alive and working. Tony Visconti, meanwhile, kept assuring us, “He’s not dying any time soon, let me tell you.”

Would that it were true. How could Bowie die, anyway? Surely there was no messy mortal at the center of all that radiant expression of life. Surely he was just a manifest Foucaultian process, an anthropomorphized discursive object, never actually material. At most, should the time come, he’d simply act out his departure as depicted on “The Venture Brothers” — saying, “Gotta run, love,” changing into an eagle, and flying away. When the news arrived on Monday, reality bit. As Bowie sang in the title track to his “Reality” album, “Now my death is more than just a sad song.” I wasn’t even the biggest Bowie fan in the world, not by a long shot, yet it was hard to concentrate for the rest of the day. Bowie the fountainhead flows through so much of the cultural landscape; I am the biggest fan of many folks who wouldn't have had careers, wouldn't have had the courage, without the lifeblood of that flow. Watered by his life, droughted by his death. I sat in my campus office, trying to work while listening to “Blackstar,” and a creeping dread arrived: How am I going to explain Bowie to my students? And write the obit when you do

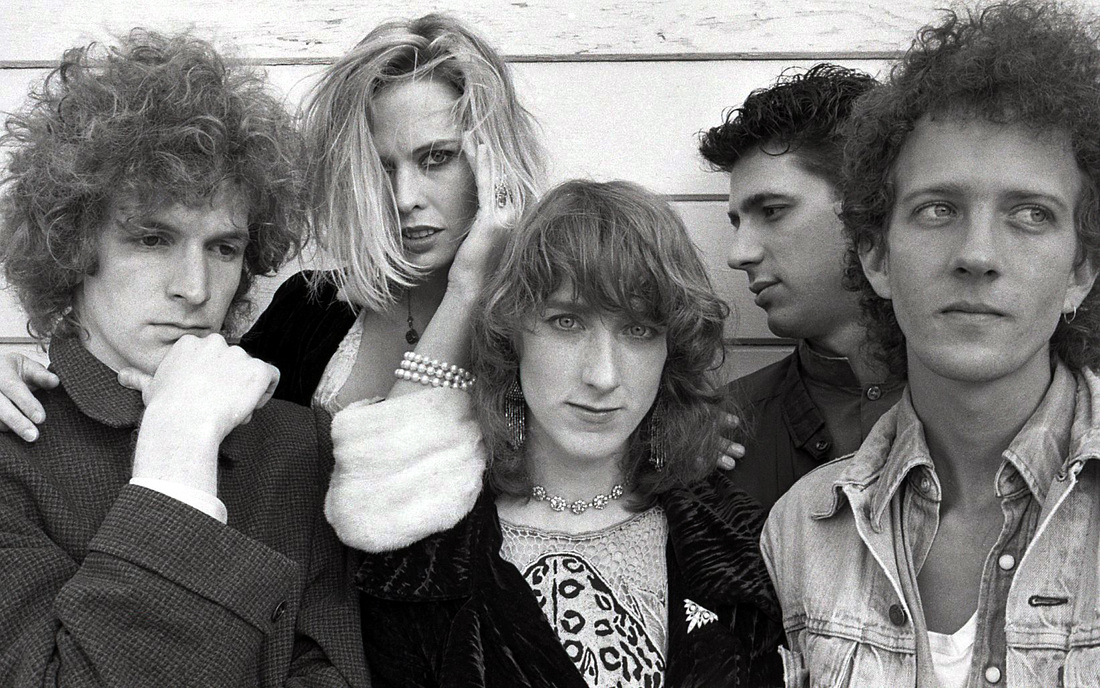

He never ran out when the spirits were low A nice guy as minor celebrities go — Scott Miller, “Together Now, Very Minor” I’ve been rightly accused of liking Beatlesque bands better than the actual Beatles. True, give me Big Star over the Fab Four any day. But given how rarely either band actually figures into my everyday universe, my dispositions are even one more generation removed. Truer, give me Scott Miller over Alex Chilton any other day. The ones who embraced the countryish side of the ’80s, they’re special. Beyond the synth-pop and college rock, the New Wave and New Romantics, even the Paisley Underground, there were the cowpunks. They were refreshingly less self-righteous than most of the pearl-snapped, No Depression-quoting blowhards the following decade. Centered in L.A., hilariously, all those crisp but gritty backbeat bands — Lone Justice (all hail), the Blasters, Blood on the Saddle, Screamin’ Sirens, the Long Ryders (didn’t they just regroup?), Tex & the Horseheads, Beat Farmers, Wall of Voodoo probably counts, as does Green on Red — in the center of which was X.

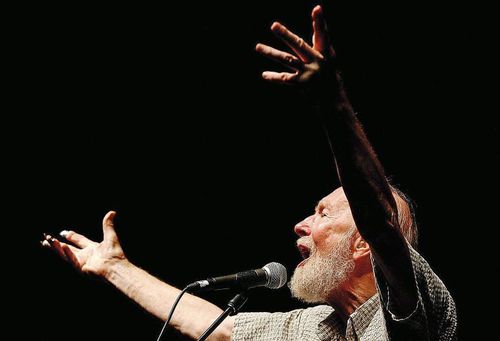

When I arrived in Tulsa, Okla., in the early ’90s, it was its own cowpunk (though by then alt-country-labeled) outpost — the twisted rootsabilly snarl (and, in concert, the chainsawed bologna) of Billy Joe Winghead, Brian Parton and his Rebels, the Boondogs (for a splendid brief time), the Red Dirt Rangers (in their rockin’ moments), Bob Collum (before his legendary hitchhike overseas), Mudville, Phil Zoellner’s bands, whoever was booked at the Deadtown Tavern and whoever drifted over from Stillwater (Cross Canadian Ragweed, Jason Boland, etc.) and … hell, anyone remember Ester Drang’s twangy offshoot, Lasso? — in the center of which was Tex. The life of Pete Seeger inspired a lot of wonderful words this week — eulogies, appreciations, retrospectives, think pieces, memories from Arlo, one singularly stupendous comic strip — and I could write a lot more. I’ll keep my belated memories brief, because Woody Guthrie’s own summation of his friend, below, is just about the best thing worth reading (and reading aloud) in remembrance of one of the greatest cultural figures this country ever produced, a living archive of every generation thus far of American folk music.

I’d forgotten J.J. Cale lived around these parts, and it’s a damn shame I was reminded of it by his obit. Cale died this weekend of a heart attack, at a La Jolla hospital just over the hill from my house.

If there’s an afterlife and ol’ J.J. winds up haunting this realm as a ghost — well, not much is gonna change. |

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed