|

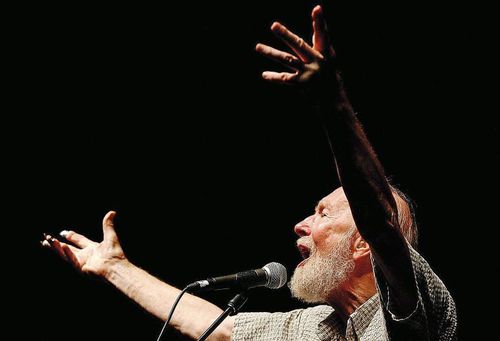

The life of Pete Seeger inspired a lot of wonderful words this week — eulogies, appreciations, retrospectives, think pieces, memories from Arlo, one singularly stupendous comic strip — and I could write a lot more. I’ll keep my belated memories brief, because Woody Guthrie’s own summation of his friend, below, is just about the best thing worth reading (and reading aloud) in remembrance of one of the greatest cultural figures this country ever produced, a living archive of every generation thus far of American folk music. Pete possessed a crackling energy that illuminated everyone within its considerable range. Few people lived as much as he did, or as long. When I interviewed Loudon Wainwright III in 2009, I carefully inquired if he’d ever thought of retiring. He used Seeger as a yardstick for his own career moves: “I figure, if Pete can do it at 90, I can do it at 63. I’m just a whipper-snapper next to Pete.” Harry Belafonte told me later: “I was just with Pete Seeger the other day … I’m amazed at his endurance, stamina, and clarity after all these centuries he’s been alive.”

I met Pete on a few occasions. He played the Woody Guthrie Folk Festival in Woody’s hometown of Okemah a couple of times. He and his wife Toshi handled the awe of the backstage mobs so smoothly. I remember chatting with him over veggie burgers about the particular virtues of gardening in the Hudson Valley. Those performances were typically radiant. In 2000, I wrote, “Over the next hour and a half, Pete got the crowd singing not only because he prompted us with each line before he sang it but because the utter joy radiating from his ruddy-cheeked smile was impossible to disallow.” Later that year, I’d meet him again in the offices of the Woody Guthrie Archives, where I was then researching. My favorite Seeger show, though, was weeks later in a Barnes & Noble on the Upper West Side — Seeger singing, smiling, high-stepping his bony legs up and down the book aisles like the Pied Piper, or the Blessed Banjoman. He returned to the Okemah festival in 2003, and I remember him saying from the stage — as he and Arlo led several thousand people standing in the pasture through “This Land” and “Amazing Grace” — “The musicians can teach the politicians that not everyone has to sing the melody.” I left during the climactic finale, because frankly I didn’t want to see it end. In my mind, I wanted Pete to always be there, still singing. Woody, though, likely was the man who knew Pete best. At least he summed him up better than most. In one of his notebooks, now safe in the Woody Guthrie Archives (songs-2, notebook-5), which has been relocated to Tulsa, Okla., Woody wrote the following remembrance of meeting Pete for the first time. Woody and Pete had just returned from Chicago in 1944, on a trip as part of the FDR election bandwagon, and Woody decided to write the account of meeting his best pal years earlier, and it’s a good’un: I met Peter Seeger in Washington one day while I was walking through the Library of Congress. He sat at a desk full of papers and looked out a window toward the Capitol Building. He rose up and took out his hand which I saw was big and bony. He was a long tall awkward boy and was nervous in every muscle. He had a lot of power in him and his words came a bashful laugh. His whole body moved as he talked and he always turned his face up toward the ceiling to laugh. Everything worried him and he seemed to get mixed up but he always — but he laughed his worries away as fast as he could think them up. His voice had a loud sound to it in that big marble hall of the library. He played a tune for me there on his banjo and it sounded better than most of the sounds in the halls of Congress. He said, “I can’t play much. Just got it. Gonna get out and hit the road and learn how.” And so we had breakfast together and talked over a few things. Pete laughed up at the cafe ceiling some more and ate a breakfast of some size. Then we shook hands and parted. He did hit the road as he said he would. He wore out a pair or two of tough work shoes up and down the mountain roads and trails of the southern mountains. I never knew just exactly where all Pete did go on this trip. I met him about a year after that in New York. He was taller, more bashful, a little more mixed up, talked more, worried more, and laughed it off more. His feet and his hands were bigger. He laughed more like he was yelling, and loud, quick, “Hahh!” He added on a many hahs as the thing would allow. He kept his banjo on him at all times like a soldier heading up to the front. When he would laugh, “Hahh!” he would hit all five of his banjo strings at the same time. We decided to go to work and pitch in all of the songs that we had collected together and write them all up into one book. We were in the room of Pete’s friend who by some funny streak of luck was a pretty girl of nineteen or twenty. She threw her powers over both of us and I’ll not bother to say how she made me feel or act, but she caused Pete to talk, to sing, to laugh, to open his mouth up toward the ceiling, “Hah!” and to strike the strings nearly loose from the neck of his banjo. All day every day he worked on the book with his banjo for a table down in the middle of the floor. He wrote with a pencil on piles of papers. He whacked his banjo several times for each page that he wrote. He sung each song through a dozen times. There were over two thousand songs. Our job was to pick out the best three hundred or so. By night Pete played in the room, out on the stairs, the roof, fire escape, alley and street. He roamed all night and walked and sung. Every brick in New York heard the sound of Pete’s voice I do believe. He strolled in parks, sat on water fountains, statues, laid down on benches, climb trees, mounted skylights and sang on the lids of garbage cans. Somebody had given him a nice old banjo, I forgot the make, but it was a good mellow one with a flesh sounding tone to it, and a ring so clear as the Tehran agreement. I never will in my whole life forget these days and nights. It was in the late days of the W.P.A. when most everybody was getting let out because of thinking communistically in capitalistic apartments. Pete learned to sing every trade union fight song in the country, we had several hundred up there on that girl’s floor. Pete played right on. His mind saw and heard everybody everywhere in this world right there in those five strings of his banjo. He sat with his feet crossed on the floor and played by day and by night. This might have all happened right there next to you. … I knew I was having some of the finest music that I had ever run onto. And I had followed it up and down roads and stairs for eight years including sofas, divans, phone booths and night rugs. That banjo had more music about it than most of the big bands turn out with thirty hours. I am bragging on the horns. Alleys shook. Dogs barked. Cats ran. Trees waved in the air. Whole streets echoed it. The birds cried it and the breezes sighed it. The fire escapes were soaked with it and windows dripped with it. A hundred years from now the iron and the concrete and the stoves and the tar will still echo and shake with the tones of Pete’s fingers chasing around over those banjo strings. I stand as only a man here trying to write down this scientific fact.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed