|

A new journal article of mine is now published: "Rock and Roll Will Never Die: Holograms and the Spectrality of Performance" in the spring issue of Spectator, the film-studies journal at USC. The work extends a conference presentation I gave at USC's First Forum in 2021. The abstract: In 2012, the rapper Tupac Shakur performed in the top slot at a major music festival — an event only notable because he had died 16 years earlier. The performance was made possible by a 21st-century digital upgrade of a 19th-century stage illusion called Pepper’s Ghost, and it ushered in a trend of creating and presenting similar “hologram” performances of posthumous pop stars. This article offers an explanation of what is seen in such a performance, examining the simulation of 3D video imagery designed to veil its mediation in order for its subject to appear unmediated, present, and “real.” Ultimately, I claim that these illusions are contemporary séances — a revival of historically spiritualist practices but one in which what is conjured is actually the deceased’s previously existing performing persona, as the concept has been extended by Philip Auslander. This cultural entity (distinct from the body and able to outlive it) is offered a new embodiment within a media system that restores the immaterial entity to the material space of the stage — a context previously off limits to the dead performer. Read the article here!

0 Comments

I've written before here about David Gunkel's research and thoughts on the social rights of robots. He's now summed up the many arguments for and against — and contributed his own, based on the philosophy of Levinas — in a new book, Robot Rights, from MIT Press. I jumped at the chance to review it, and it's finally published online.

And, hey, Gunkel referred to my review as "positively brilliant"!  Science for the People was an organization of scientists and science workers who banded together around the turn of the ’70s to express concerns about the commercialization, industrialization, and militarization of science. The group raised awareness of a multitude of issues, organized and balanced public debates (which sometimes included disrupting establishment conferences), and published a spiffy magazine for nearly a decade. Worried about how science was being used against people, SftP advocated for. In 2014, a conference was organized at UMass-Amherst to examine the group’s legacy. At the close of the event, several attending students and scholars from across the country met to discuss ways to continue the examination, even ways to revive and evolve the mission of SftP. I was fortunate to be among this group, and the result of our decision has finally been realized in a new book: Science for the People: Documents From America’s Movement of Radical Scientists, now available. Attending San Diego’s famous annual Comic Con is a breeze — when you’re an STS grad student, at least. The lines for the Netflix trailers and movie sneak-peeks and TV cast conversations? Long, like crazy-long. The lines for the science panels? What lines?

I think I possess the very opposite of a macabre personality, but I’m thinking a lot today — in grave detail, shall we say — about my father’s corpse.  This month saw publication of The Oxford Handbook of Music & Virtuality, containing my chapter, "Hatsune Miku, 2.0Pac and Beyond: Rewinding and Fast-forwarding the Virtual Pop Star." In it, I survey a history of virtuality in pop music stars, from the Chipmunks and the Archies up to Gorillaz and Dethklok — many of the non-corporeal, animated characters that presaged current virtual pop stars like Hastune Miku and the Tupac resurrection. When researching and writing about (or designing and producing) hologram simulations, there’s always an initial coming-to-terms with the terms.

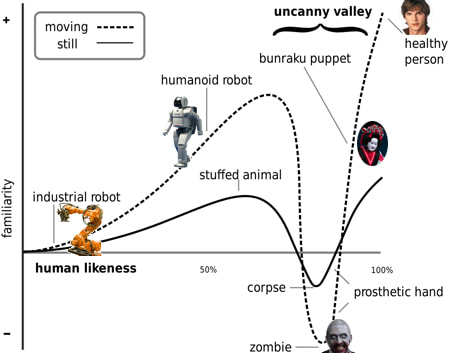

When I analyzed the discourses of simulation designers, nearly all of them made some attempt to square and/or pare the language of their field. Designers and artists usually opened interviews with this, eager to make sure I understood that while we call these things “holograms” they’re not actual holography. “The words ‘hologram’ and ‘3D,’ like the word ‘love,’ are some of the most abused words in the industry,” one commercial developer told me. Michel Lemieux at Canada’s 4D Art echoed a common refrain: “A lot of people call it holography. At the beginning, 20 years ago, I was kind of always saying, ‘No, no, it’s not holography.’ And then I said to myself, ‘You know, if you want to call it holography, there’s no problem.’” In my own talks and presentations, I’ve let go of the constant scare-quotes. The Tupac “hologram” has graduated to just being a hologram. It gets stickier when we begin parsing the myriad and important differences between virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR). Many of us think we have an understanding of both, largely as a result of exposure to special effects in movies and TV — where the concept of a hologram underwent its most radical evolution, from a mere technologically produced semi-static 3D image to a computer-projected, real-time, fully embodied and interactive communication medium — but it’s AR people usually grasp more than VR. They’ll say “virtual reality,” but they’ll describe Princess Leia’s message, the haptic digital displays in “Minority Report,” or the digital doctor on “Star Trek: Voyager.” Neither of these are VR, in which the user dons cumbersome gear to transport her presence into a world inside a machine (think William Gibson’s cyberspace or jacking into “The Matrix”); they are AR, which overlays digital information onto existing physical space. Yet both VR and AR refer to technologies requiring the user to user some sort of eyewear — the physical reality-blinding goggles of OculusRift (VR) or the physical reality-enhancing eye-shield of HoloLens (AR). Volumetric holograms — fully three-dimensional, projected digital imagery occupying real space — remain a “Holy Grail” (see Poon 2006, xiii) in tech development, and we may need a new term with which to label that experience. One developer just coined one. If your Roomba chews up the fringe on your favorite Oriental rug, is it OK to punch it? If an algorithm recommends a movie to you, and the movie turns out to be crapola, to whom do you direct your online flames? If a drone independently computes a tactical course correction and flies into the wrong airspace, igniting international tensions, would war be averted if our rep stood in the UN assembly and assured everyone, “The drone gravely regrets its error”?

Machine ethics, robot rights — these topics keep popping up in my world. In the last year, I’ve attended three talks addressing various shades of the subject. What an invigorating weekend at UMass-Amherst for the one-off conference about Science for the People! Organized by Sigrid Schmalzer and her comrades at the university's enviable Social Thought & Political Economy program, the two-day gathering assembled nearly 200 people — most of them former members of Science for the People, and many of them enjoying the reunion with colleagues and cohorts — to discuss the legacies and lasting impacts of the group's resistance, publications, and educational efforts.

Founded in 1969, SftP became a diverse national network of scientists commonly concerned about the increasing militarization and corporatization of scientific research. Through organized confrontations at established science conferences, various street-level social projects, and an impressive, eponymous bimonthly magazine that published for 15 years (now neatly archived online), SftP sounded early alarms about issues ranging from drones (as early as 1973) and computer surveillance to the commercialization of biotechnologies and genetic manipulation. Early in the conference, the consensus was clear: these issues have grown only more urgent, and much work remains. |

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed