|

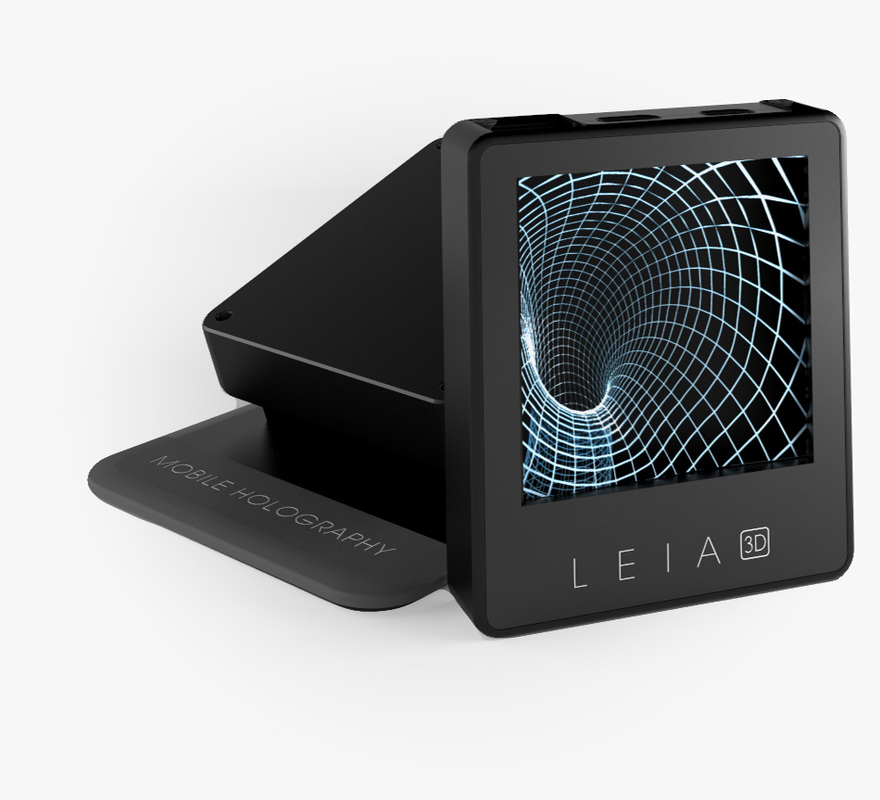

When researching and writing about (or designing and producing) hologram simulations, there’s always an initial coming-to-terms with the terms. When I analyzed the discourses of simulation designers, nearly all of them made some attempt to square and/or pare the language of their field. Designers and artists usually opened interviews with this, eager to make sure I understood that while we call these things “holograms” they’re not actual holography. “The words ‘hologram’ and ‘3D,’ like the word ‘love,’ are some of the most abused words in the industry,” one commercial developer told me. Michel Lemieux at Canada’s 4D Art echoed a common refrain: “A lot of people call it holography. At the beginning, 20 years ago, I was kind of always saying, ‘No, no, it’s not holography.’ And then I said to myself, ‘You know, if you want to call it holography, there’s no problem.’” In my own talks and presentations, I’ve let go of the constant scare-quotes. The Tupac “hologram” has graduated to just being a hologram. It gets stickier when we begin parsing the myriad and important differences between virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR). Many of us think we have an understanding of both, largely as a result of exposure to special effects in movies and TV — where the concept of a hologram underwent its most radical evolution, from a mere technologically produced semi-static 3D image to a computer-projected, real-time, fully embodied and interactive communication medium — but it’s AR people usually grasp more than VR. They’ll say “virtual reality,” but they’ll describe Princess Leia’s message, the haptic digital displays in “Minority Report,” or the digital doctor on “Star Trek: Voyager.” Neither of these are VR, in which the user dons cumbersome gear to transport her presence into a world inside a machine (think William Gibson’s cyberspace or jacking into “The Matrix”); they are AR, which overlays digital information onto existing physical space. Yet both VR and AR refer to technologies requiring the user to user some sort of eyewear — the physical reality-blinding goggles of OculusRift (VR) or the physical reality-enhancing eye-shield of HoloLens (AR). Volumetric holograms — fully three-dimensional, projected digital imagery occupying real space — remain a “Holy Grail” (see Poon 2006, xiii) in tech development, and we may need a new term with which to label that experience. One developer just coined one. Leia 3D — yes, the patron of this field is St. Leia Organa — is a Silicon Valley startup marketing a small device producing interactive holographic imagery that appears to emerge from the plane of the device’s modified LCD screen, requiring no visual gear. Their chief selling point seems to be the smoothness of their backlight technology: “The result is content that looks 3D from any viewpoint, by any number of viewers, with a seamless sense of parallax — no more breaks, ghost images or ‘bad spots’ that plague lenticular displays.” (Also see Fattal et al. 2013) The video demos thus far are high on electronica soundtracks but low on wow factor; then again, a single-lens video camera doesn’t exactly capture this kind of effect. The company refers to what it produces as “holographic reality,” and founder David Fattal posted to the company’s blog just over a week ago something of an attempt to root that new term. His distinction: VR and AR require eyewear; HR does not. Fattal explains: One the one hand, Virtual and Augmented Reality (VR / AR) devices will immerse people in the digital world with a headset. These technologies are important ways of re-imagining how we can interact with digital data, but they are all-encompassing and seek to make the user part of the digital. This change in subjective orientation is important. VR (especially) and AR (to a lesser degree) seek to “make the user part of the digital,” to transport the user (the subject’s presence) into the box. The concept of HR fully brings the digital content out of the box to co-exist with the user in physical space, requiring no reorientation of the subject. Bits exist among atoms. Holographic reality is just reality, with a different role for the digital.

That role, however, seems to require new situated practices for human-computer interaction — namely the clearing or creation of some new spaces in which that HCI can wield its greater embodiment. If HR tech truly evolves to produce viable mid-air imagery — especially digital objects and presences that can be interacted with and manipulated by hand — then the explorations of starry-eyed cultural texts from “Wars” to “Trek” and everything in between begin to seem less like fiction and more like rehearsal. What do we not see depicted in many sci-fi worlds? Keyboards, mice, a predominance of screens. The textual information, the maps, the objects and, increasingly, the people communicating are widely displayed as projected digital content — and the spaces in which this occurs look nothing like the home offices, workplaces, or corporate cubicle farms of today. You’re reading this on a screen right now, but stop and consider the space you’re in. How would it have to change to accommodate interaction with digital content projected upward from your mobile device or outward from elsewhere in the room? HR requires thinking about physical space in new ways and from new angles. Leia is one of several companies attempting to colonize these new spaces, and social science would benefit us all by further investigating these new possibilities while the tech is young. Plus, the market is already getting ahead of some scholarly research in recognizing the dramatic nature of this transformation in HCI. Just last week, a corporate think-tank heralded the looming age of AR in a white paper titled “Augmented Reality: The Paradigm Shift Begins” (its title suggesting a Kuhn-level rupture in thinking). The report discusses AR in contrast with VR (not HR) and points to the primacy of heads-up displays, examining the failure of Google Glass and predicting the success of Microsoft’s HoloLens, concluding that AR tech “will likely eclipse most other forms of consumer data interfaces within five years.” That’s swift progress for something the report says is still “currently at the hobbyist level”; however, AR is already “beginning to intrude on the consumer consciousness” — somewhat via actual tech being produced but moreso via the widespread exposure to the basic VR/AR/HR concepts explored for decades now in culture, sci-fi and otherwise. “AR is becoming common enough that [TV and film] producers feel comfortable including it routinely, rarely stopping to explain exactly what it is,” the report says. “AR has reached a point where audiences know it when they see it.” What they see are holograms, at least as we apply that term now. The OED’s definitions of “holographic” go back to the 15th century, yet its most current example dates to just 1971. Even the original optical and laser sciences of holography evolved considerably past that, not to mention the transformative epigenetics the overall concept of projected 3D imagery has endured since “Star Wars.” HR is a useful framework in which to explore emerging digital display and projection technologies (though the acronym will have to wrested from human resources and the term differentiated from some heady theoretical physics), and the sciences would benefit from thinking in terms of this shift in perspective, however paradigmatic it may or may not be.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed