|

In the early 1990s, folk-rocker John Wesley Harding released one of the best B-sides around: “When the Beatles Hit America.” A lengthy narrative about a dreamed-up Fab Four reunion, it envisions both cultural and technological contexts for a new Beatles event — and this is back when only one of them was dead. In Harding’s epic ballad, the Beatles are going to reunite on stage, all “due to a miracle marketing strategy / beyond the realms of reasonable possibility.” The lyrics realistically dramatize the build-up (securing the film rights, sponsorships, talk show scheduling, etc.) and then inject a bit of scifi to make it happen (the manager of the new Beatles is “made up of cloned parts of Col. Tom Parker and Col. Sanders”). Ringo won’t actually play, though, because he’s been replaced by a more accurate drum machine; he’s “disappointed to find that no one / needs him anymore except for the vibe.” Lennon, meanwhile, is substituted with a life-size cardboard cutout, and then — per today’s news, in a way — he speaks to the press, sounding suspiciously like some old recordings: John, who was never the quiet one makes all his press contributions from his old songs -- in tune, in time, and with the backing track behind him And when they ask him how it’s been in the studio, he says, “It’s been a hard day’s night” And no one understands him, but he always was the cryptic one … Funny stuff, but now prescient. Today marks the release of the Beatles’ latest — and allegedly last — technologically resurrected cast-off, a “new” old song called “Now and Then” that features the two living members and the two dead ones reunited in eerily perfect harmony and time. As a scholar who studies the uncanny properties of media and its inherent constructions of liminal spaces between life and death, well, I have some initial thoughts.

0 Comments

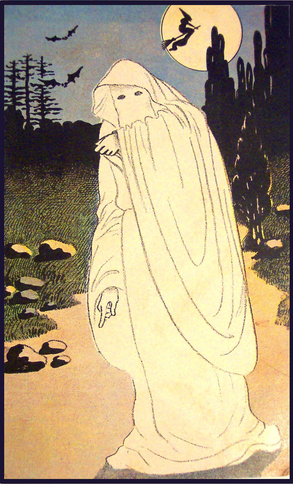

A new journal article of mine is now published: "Rock and Roll Will Never Die: Holograms and the Spectrality of Performance" in the spring issue of Spectator, the film-studies journal at USC. The work extends a conference presentation I gave at USC's First Forum in 2021. The abstract: In 2012, the rapper Tupac Shakur performed in the top slot at a major music festival — an event only notable because he had died 16 years earlier. The performance was made possible by a 21st-century digital upgrade of a 19th-century stage illusion called Pepper’s Ghost, and it ushered in a trend of creating and presenting similar “hologram” performances of posthumous pop stars. This article offers an explanation of what is seen in such a performance, examining the simulation of 3D video imagery designed to veil its mediation in order for its subject to appear unmediated, present, and “real.” Ultimately, I claim that these illusions are contemporary séances — a revival of historically spiritualist practices but one in which what is conjured is actually the deceased’s previously existing performing persona, as the concept has been extended by Philip Auslander. This cultural entity (distinct from the body and able to outlive it) is offered a new embodiment within a media system that restores the immaterial entity to the material space of the stage — a context previously off limits to the dead performer. Read the article here!

In this week’s episode of the CBS crime drama NCIS, detectives interview an unusual person of interest in a murder case: the victim herself.

Older narratives might have made this possible via a traditional spiritualist séance, with interested parties holding hands around a table as Madame Blavatsky channeled the spirit of the dead in order to ask directly, “Whodunnit?” In today’s séances, however, the medium has become digital media: complex technical imagery systems that archive a person’s likeness and prerecorded messages intended to be posthumously played back for survivors. Several such apparatuses exist already, though most are still in experimental and prototype stages. This NCIS episode, however, brings to the broader public a fairly accurate depiction of what such “holograms” currently look and seem like, as well as providing some early fodder for conversations about how they might be integrated into social realities. That is, people often ask, “Why in the world would you make a hologram of yourself?” Here’s a pop-culture text that starts grappling with a few real answers. Get Back — Peter Jackson’s extraordinary new reboot of Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s 1969 documentary footage following the Beatles’ penultimate recording sessions — has been revelatory in numerous ways, from its prompting of astute reconsideration of Yoko Ono’s much-maligned cultural narrative to final proof that Billy Preston utterly saved the day. The remarkable technology used to revive these old reels (and the audio) is important to attend to not only for its importance to the future of film restoration but for its increasing intrusion into filmmaking; Get Back is a highly computed film, perhaps the first movie many have seen with such dramatic and artistic contributions by an algorithm (“And the Oscar for Best Algorithm goes to…”?) — to the point that the documentary’s rotoscopic computation of imagery and sound can be seen as the construction of a kind of virtual reality.

In addition to this surface virtuality of the image, however, I’m interested in the virtuality of the individuals shown through that imagery — and the ways Get Back is less a documentary about live human beings than it is about a socially constituted band of living ghosts. |

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed