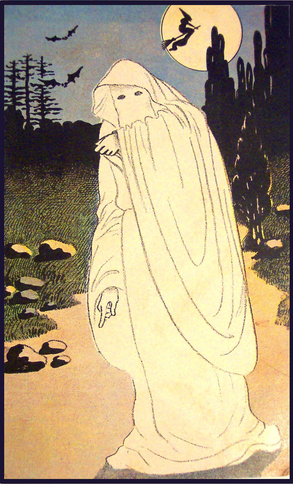

As far back as the 1300s, dead people who continued mixing with the living were represented with a shroud, though these usually wrapped around a skeleton. The Psalter of Robert de Lisle shows three such spooks in various states of undress as they attempt to advise three nobles to be goodfellas (a la Jacob Marley warning ol’ Scrooge to mend his miserly ways). By the next century, the idea of the walking dead assigned to a specific fashion choice was common enough that British thieves seized on the imagery, dressing in white sheets in order to scare the bejesus out of people just long enough to grab their money. (The use of the white sheet to scare commoners would be revived after the U.S. Civil War by the Ku Klux Klan, which used white robes and hat with eye holes both to mask the identity of their members and to tap into spectral fears. It’s also why bedsheet ghosts aren’t depicted much anymore with pointy tops.) On stages, into the 1500s and beyond, ghosts were signified by actors’ costumes (flowing robes or often armor) and makeup (perhaps a distinct pallor). Hamlet’s father, for instance, was and still is usually portrayed by an actor in chain and helmet. The visuals communicated individual identity; the dialogue communicated corporeal state. Some argue that ghosts appearing in more human form drew greater sympathy from audiences. Ghosts grew quite busy haunting the Victorian era, in a variety of guises — depending on the source and intent of the depiction. Early in 1804, rumors of a white-sheeted ghost haunting the Hammersmith neighborhood of London led to the death of a bricklayer, shot in the head by a local who mistook his trade’s traditional white garments for the ghost (and somehow thought a bullet would pierce a spirit). The resulting murder trial was sensational and likely firmed up the social concept of ghosts clad in white. In the theater, though, actors were still depicting spirits without sheets. The 1852 premiere of “The Corsican Brothers” by Dion Boucicault instituted a device specially for the manifestation of a ghost; known still as the “Corsican trap,” its hidden ramp and trolly made an actor appear to emerge from the stage floor, as Jeremy Brooker explains, “rising into view on a wheeled trolley running up an inclined ramp through a slot cut from left to right across the stage. The mechanism was concealed by a strip of narrow wooden slats ‘like the flexible surface of a roll top desk’ from which the actor emerged through an oval ring of black bristles.” The appearance stunned and shocked audiences and contributed to enormous success for an otherwise unremarkable play. Just a decade later, though, John Henry Pepper adapted a common optical illusion into a famous theatrical spectacle that came to be called Pepper’s Ghost. Using hidden mirrors and sheets of glass, he was able to reflect the image of an offstage actor onto a stage as if they were present. Audiences would, at first, assume the image to be a body in the space, but when actors actually on the stage interacted with the image in a way that revealed it as “noncorporeal” — say, running the image through with a sword, or directing the image to walk through a wall — shock and awe ensued. (Pepper’s Ghost is a frequent case in my media-archaeological research related to holograms; Pepper’s original basic arrangement is the basis for contemporary illusions that really do bring back the dead.) The catch: Pepper’s Ghost depicted ghosts not just as corporeal bodies, the way the theater was doing at the time, but upped the ante by projecting the imagery as almost photo-realistic (if the apparatus was “tuned” just right), allowing for actors to not only be displayed as ghosts but to perform spectral functions, as well. The result was a representation of ghosts as human bodies, signified as spectral only by virtue of their revealed insubstantiality. (The concurrent fad of “spirit photography” also upheld the notion that ghosts were simply human bodies in spectral form.) Pepper’s aim was ideological: he not only presented the spectacle, he concluded with an explanation of its production. This was designed to promote ideals of modernity and capitalism at the core of the mission behind the science museum where he developed the illusion, the Royal Polytechnic Institution. Both Pepper and the Polytechnic also sought to counter the spiritualism movement rising at the same time, in which mediums claimed to communicate with the dead, often by manifesting some sign of their presence. In an interview, Lisa Morton, author of Trick or Treat? A History of Halloween and The Halloween Encyclopedia, described some of the practices by unscrupulous mediums, which often included the easy trick of using materials easily at hand — like sheets. “It was a big deal if they could — quote, unquote — materialize a spirit,” she said. “And they could often do this by rigging up a sheet.” As the 20th century dawned, pop culture’s shorthand for spirits was widely settled as the floating white sheet. As dressing up for Halloween and trick-or-treating became widespread social activities, a go-to homemade costume for those without the time, energy, or money to spend was easily snatched from the linen closet and doctored with scissors. The depiction was enshrined in animated imagery from Disney to Casper, Charlie Brown to Scooby Doo. Still, in the realm of theater and film, ghosts usually continued to be portrayed by actors. It’s cheaper that way; special effects are very expensive. The girls in The Shining, Bruce Willis in The Sixth Sense — these are characters meant to evoke greater emotional sympathy than the mere spook factor of the sheet ghost. Then again, David Lowery’s 2017 film A Ghost Story is a remarkable narrative about a dead musician who haunts the house he shared with his wife. The character is played by Casey Affleck, but the entire posthumous depiction (most of the film) has Affleck underneath an iconic white sheet with eye holes — a death shroud, no less, the sheet his body was covered with following a car accident. Then again, film itself is a ghost story — a ritual experience of haunting. Those flickering phantoms on the screen. Radio, too — those disembodied voices in your room. This is the perspective of Jeffrey Sconce’s Haunted Media, the idea that modern communication technologies produce an inherently spectral experience, that ghostliness is hard-wired into our electronic mediations. Indeed, John Durham Peters writes about how the very terms at the core of media studies (media and communication) derive in part from those earlier attempts to speak with spirits (mediums and communing with the dead). Roland Barthes believed every photo invoked the death of its subject. For media-studies scholars in this frame of mind, every day is Hallowe’en!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed