|

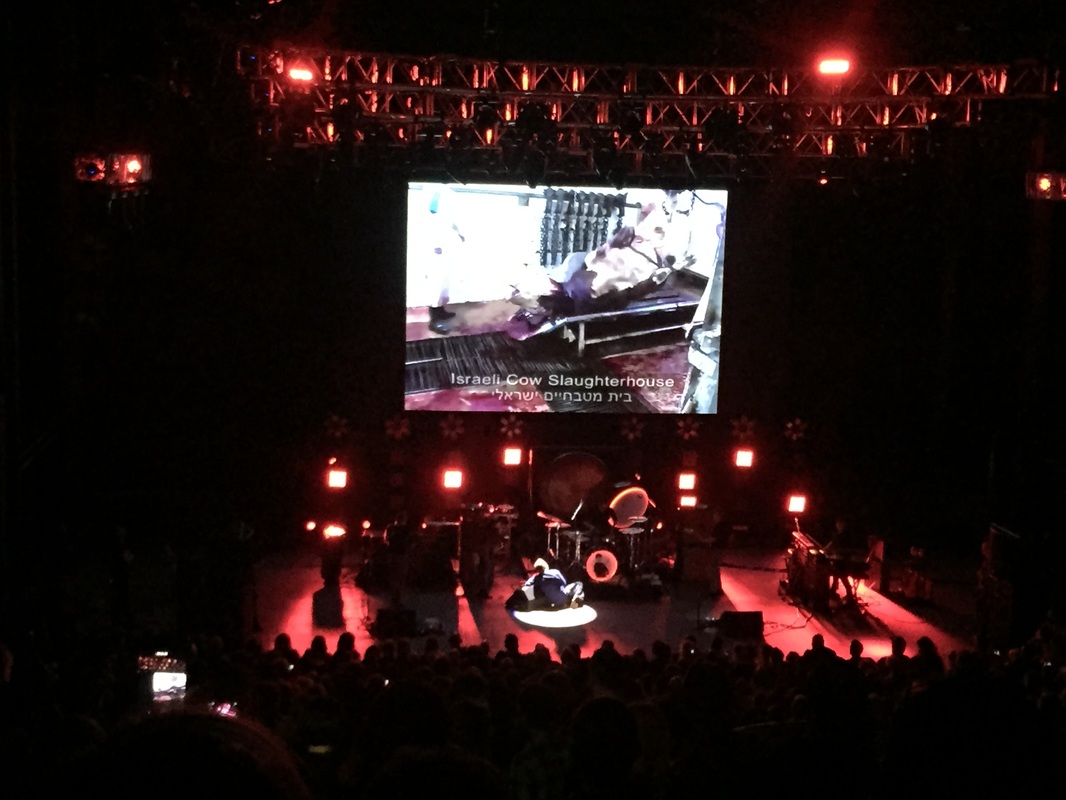

I just returned from Denver, where my best friend David and I saw Morrissey in concert at Red Rocks. I’d intended merely to wax nostalgic about this — we’d seen him on his first solo tour in ’91, also in Denver, and I’ve much to say about how rewarding it’s been to grow old with Moz — but something he did at the end of his show makes for a poignant follow-up to my previous ramblings about the evolution of protest music performance.

0 Comments

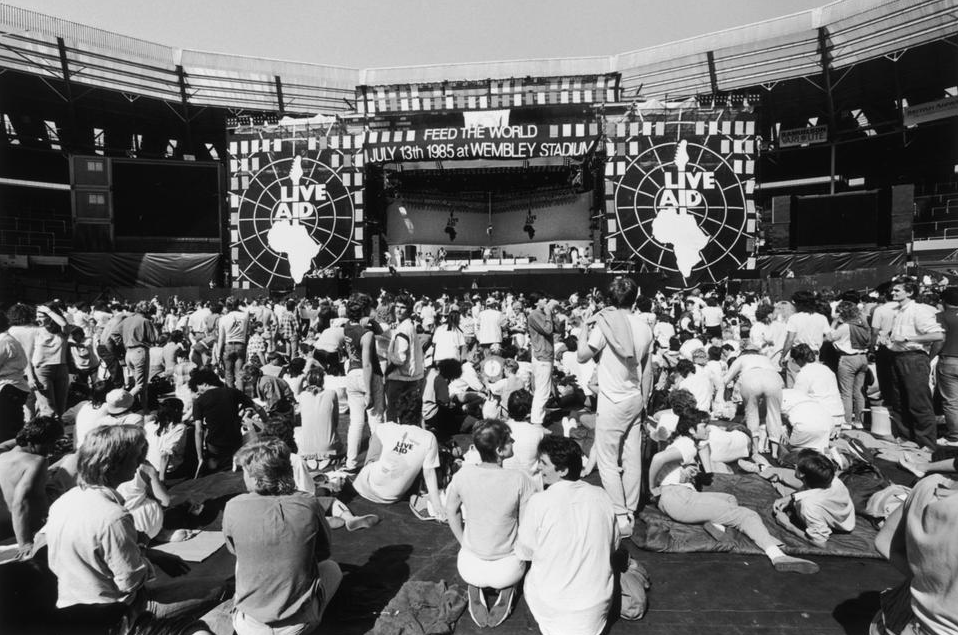

This week marks the 30th anniversary of Live Aid. Memory flashes I’m still able to conjure from my aging brain: Paul Young’s flouncy pirate cuffs, the poetic irony of Geldof’s mic failing during his own set, Elvis Costello’s classy choice of "an old northern English folk song," the Pretenders’ playing surprisingly laid-back, of course U2’s career-making set and Queen’s delivery of the world’s quintessential arena-rock performance. Political opinions aside, it was an unequaled day of, let’s say, musical performativity.

The DVD set of the concerts bears a postmark-like stamp that reads, “July 13, 1985: The day the music changed the world.” Thirty years have allowed for much evaluation of nearly all the changes wrought (not all for the better; read this excellent piece about Live Aid’s “corrosive legacy”). What it did change — drawing from research I conducted a few years ago into protest music (or the lack thereof) at Occupy Wall Street events — was the common conception of popular musical protest practice, resituating it from the open street to the ticketed arena, as well as the establishment of celebrity at the very core of such practices. |

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed