|

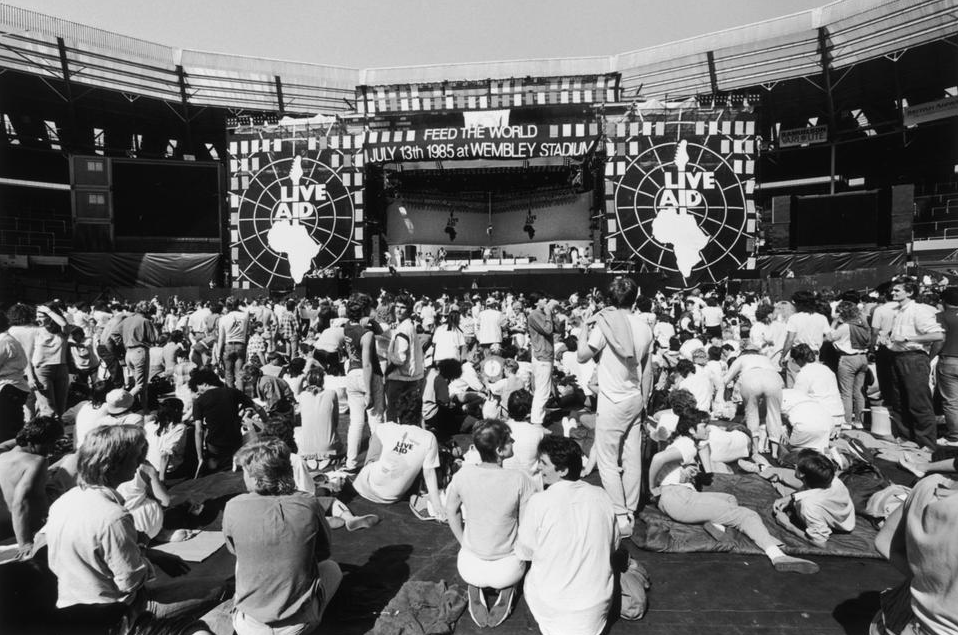

This week marks the 30th anniversary of Live Aid. Memory flashes I’m still able to conjure from my aging brain: Paul Young’s flouncy pirate cuffs, the poetic irony of Geldof’s mic failing during his own set, Elvis Costello’s classy choice of "an old northern English folk song," the Pretenders’ playing surprisingly laid-back, of course U2’s career-making set and Queen’s delivery of the world’s quintessential arena-rock performance. Political opinions aside, it was an unequaled day of, let’s say, musical performativity. The DVD set of the concerts bears a postmark-like stamp that reads, “July 13, 1985: The day the music changed the world.” Thirty years have allowed for much evaluation of nearly all the changes wrought (not all for the better; read this excellent piece about Live Aid’s “corrosive legacy”). What it did change — drawing from research I conducted a few years ago into protest music (or the lack thereof) at Occupy Wall Street events — was the common conception of popular musical protest practice, resituating it from the open street to the ticketed arena, as well as the establishment of celebrity at the very core of such practices. The morphing of mega-events The template of large-scale fund-raising and awareness-generating music events was fashioned largely during the 1970s — the Concert for Bangladesh (1971), A Poke in the Eye (1976, kicking off what would become Amnesty International’s successful Secret Policeman’s Ball concerts in 1979 and 1981), A Gift of Song: The Music for UNICEF Concert (1979), the great No Nukes shows (1979), and the huge Nuclear Disarmament Rally concert and march in New York City (1982). UMass-Boston’s Reebee Garofalo calls these “mega-events” — a new organizing and presentation principle, concerts and products made with the intent to raise awareness of causes or crises and subsequently mobilize participants, with music as the primary medium of information and community. The subsequent examples contemporary to my decade — the Band Aid records, the Farm Aid concerts, the music made against apartheid and in support of Greenpeace — we referred to, mostly derisively, as “charity rock.” Live Aid had its problems, to be sure. Allocation of the funds for the Ethiopian project has been scrutinized for years. The most damning musical criticism of the event was its utter lack of music from the country/continent it claimed to be spotlighting. In the previous sentence’s slash-mark, too, lurks another of Live Aid’s cultural crimes: fostering the conflation of diverse countries and politics into a single geographic symbol — Africa as one big lumped Other. (At least one scholar thankfully has linked this Othering process to Edward Said’s Orientalism.) Garofalo’s observations followed the work of R. Serge Denisoff and were contemporary to Ron Eyerman in noting a particularly passive shift in the developing practices of musical propaganda, writing: “With the decline of mass participation in grassroots political movements, popular music itself has come to serve as a catalyst for raising issues and organizing masses of people.” In so doing, the popular perception of social protest shifted from the public sphere to the capitalist marketplace. Raising awareness or funds had to be an event (the more mega- the better) and situated within networks of economic exchange, thus requiring access to resources, facilities, and power, which transformed masses into passive spectators rather than active participants. The back end of this transformation was illuminated for me while marching through the streets of Austin, Texas, during the SXSW festival in 2012. A group of about a hundred people (pictured above), organized via existing Occupy communication channels, gathered near the state capitol and marched (correction: danced, thanks to a mobile PA that rolled along with us) through streets already crowded with festivalgoers. Destination: Tom Morello’s late-night official SXSW showcase. Along the way, literature was distributed, signs hoisted, awareness to numerous issues at least momentarily piqued. But one young buck, effervescent and glassy-eyed in his cups, stopped to inquire what the ruckus was about. “You can just do that?” he sputtered. “You can just start marching through the streets?! Hell yeah!!” On a club stage that night, Morello performed a set of his socially sharp folk-rock tunes, ending his official set indoors but continuing the show (and the message-mongering) back in the street outside the venue, scraping out songs with his acoustic guitar and leading the crowd in a raucous sing-along of Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land.” (Read my full account here.) Indeed, protest singing in the street almost requires an acoustic guitar. What other instrument travels as well or fosters communal harmony (and melody) on the move? I tend to celebrate music that challenges or complicates the baby-boomer norm of musical protest — that threadbare costume of the scraggly Dylanesque troubadour — and it’s always fascinating when I ask students to share socially conscious music they’ve heard and/or enjoy. My examples range from the well-produced emo-pop of Easterhouse (railing is it is with painfully earnest socialist rallying cries) to the espadrilles-and-gingham jazz-pop of the Style Council (perhaps the height of New Pop’s efforts at remaining topical while still trying to sound like the radio), and undergrads educate me about intriguing artists from Dumbfoundead to Killer Mike. Live Aid certainly wasn’t the root of such sonic diversity, but it helped affirm it. Music at Occupy

But what of that evolution of protest music, its sound, its utilization? Decades after Live Aid, American citizens peacefully protested under the banner of Occupy Wall Street. I was still a music critic in the fall of 2011, but I had also begun my graduate studies; the two sites of inquiry merged for their first potent joint project, which became a conference paper for NCA the following year. Many in the news media were asking of Occupiers, “What’s their message?’; in my corners, however, the main question seemed to be, “Where’s their music?” Even the U.S. invasion of Iraq eight years earlier inspired anti-war rhetoric from R.E.M., the Beastie Boys and many others. Greg Kot, across town at the Chicago Tribune, remarked, “You would think that the Occupy Wall Street movement might've sparked a few protest songs by now.” Other journalists went a step further and pointed out that protest music has been a rarity since 1990s. One essay noted that if you look at the popular music charts, there’s a distinct impression “that America has been one big party since 2001, despite the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, two major wars, a wobbly economy and a bitterly divided government” and that “the recent popular manifestations of that unrest, the tea party and Occupy Wall Street movements, so far seem to have been largely lost on popular music.” I suspected that the second question contributed something to the first. Music abounded in Zucotti Park and other national Occupy sites, but it possessed a difference character and presence. Most significant were the drum circles — I remain dismayed that still there seems to be no study of the particularly effective powers of communication wielded by those controversial drummers. As to protest music in the more conventional sense, it was indeed quite conventional. Suggestions have been made as to the (alleged) absence of new protest music, including the more individualist experience of contemporary music (isolating earbuds vs. communal listening), the usual apathy and cynicism attributed to whatever generation is currently young, and the various perils of social media. Theoretically, there’s a good argument that the Natalie Maines/Dixie Chicks comment about being ashamed of George W. Bush — and its surprisingly violent backlash — may have caused an actual “spiral of silence.” My own initial hypothesis was that new songs were out there — just harder to find. So I went searching for the music of Occupy, using Denisoff’s definitions of a “propaganda song” (identifiable authorship, managed transmission, a more fixed time/place) as opposed to a “folk song” (usually anonymous, handed-down, altered for each generation) and looking at Occupy Wall Street in the context of a Live Aid-like “mega-event” as Garafalo described. Occupy, particularly the New York encampment, began as just such a mega-event. As mega-events do, it attracted a lot of celebrity cultural capital. The first spotlighted performers at the allegedly youthful Occupy were white-haired icons from the ’60s: Crosby & Nash, Joan Baez, Arlo Guthrie, Jackson Browne, Pete Seeger. Each came out and sang songs from their ’60s heyday, attempting to apply those messages to the current situation. (Folk protest often launches via cultural remediation. The first songs employed by the anti-war movement in the ’60s had been borrowed from the previous folk-protest wave in the ’40s.) By the very nature of Occupy, no one person embodied its causes. The media, however, went looking for celebrity faces, which these old musical troopers easily provided. When I went looking for protest music actually related to Occupy, I found two camps drawn from the contexts of celebrity and mass. I plumbed two media sources and conducted cursory content analyses through both sources to generate top-10 lists of the most popular songs during a year of popular online discourse about Occupy. The first set was generated from Google News alerts I received for the search terms “occupy” and “song” from Oct. 1, 2011, to Sept. 30, 2012. From each media source, I pulled out every mention of a song in the context of an Occupy discussion or a performance at an Occupy event. That generated the following list of the 10 most frequently mentioned songs within discussions about Occupy: 1. “World Wide Rebel Songs,” Tom Morello/the Nightwatchman 2. “We Take Care of Our Own,” Bruce Springsteen 3. “Hell No,” Nanci Griffith 4. “Surrender,” Angels & Airwaves 5. “Part of the 99,” Woodbrook Elementary School in Charlottesville, Va. 6. “We Stand as One,” Joseph Arthur 7. “If There Ever Was a Time,” Third Eye Blind 8. “SHOCK-YOU-PY!,” Jello Biafra & the Guantanamo School of Medicine 9. “I Get By,” Everlast 10. Various Artists, “Occupy This Album” The use of Google News alerts was my attempt to build a list based on the rhetoric within the professional media. However, I also sought to include in the analysis songs circulated outside professionalized media discourse. For that I turned to YouTube. Using the same search terms (“occupy” and “song”), I ranked search results in descending order based on the number of views the video or audio had received within that same one-year span. That generated the following very different list of the 10 most-mentioned Occupy-related songs: 1. “I Get By,” Everlast 2. “Mama Economy,” Tay Zonday 3. “Anonymous Music,” Anonymous Occupation Alliance 4. “Black Flags,” Atari Teenage Riot 5. “We Are the Many,” Makana 6. “The End of the World,” Lupe Fiasco 7. “Distractions,” Talib Kweli 8. “Save the Rich,” Garfunkel & Oates 9. “Don’t Fuck With My Money,” Penguin Prison 10. “Got Me Surrounded,” Soles of Passion In comparing the song charts, a few contrasts leap out. The media list, of course, is mostly known quantities — names that, at least within popular music, one might recognize — while the YouTube list contains some amateur productions and lesser-known artists. (Springsteen’s song from the media list had millions of views on YouTube, but it’s not on the second list because it didn’t rank on the site when including the search term “occupy.” Media sources at the time were connecting Bruce’s music to Occupy much more than he actually did. People posting and commenting on YouTube — not so much.) Also, there’s only one crossover between lists: Everlast. Stylistically, there are differences, too. The media list spotlights classic rock, alt-rock, country-rock, one (sorta) hip-hop song. On the social-media site, the sample is much more diverse: hip-hop (4), comedy (2), punk rock, folk, adult contemporary, and country. The major themes of the songs were in line with Denisoff’s stated goals for propaganda songs: community/unity (“We Take Care of Our Own,” “We Stand as One,” “We Are the Many”), criticism, of both people and institutions (“Distractions,” “Part of the 99,” within this is the comedy: “Save the Rich,” “Mama Economy”), defiance, of institutions (“World Wide Rebel Songs,” “Hell No,” “SHOCK-YOU-PY!”), and action that people can take (“Black Flags”). Several straddle those categories; “If There Ever Was a Time,” for instance, criticizes, promotes defiance, then encourages action. From those categories, we see another split between the sample sets. The media list has more community and defiance songs, perhaps showing a gatekeeping function letting through mostly songs dealing with drama, confrontation and dissent. Notably, the media reports frequently refer to songs as being “co-opted” by the movement. The YouTube list is much more granular, more critical and message-based. YouTube commenters and artists discuss the songs as especially written for the movement. So, yes, there was Occupy protest music. Quite a lot, really — but while music may still be a feature of social movements, it’s no longer a primary communication tool within them. A key factor in Denisoff’s recruitment function for propaganda music (which Eyerman built on later) is that it provides us not only information about the movement but a space in which to weigh and consider that information. Propaganda music once served an important civic role as what I called an “ideological rehearsal space” — at least a momentary safe haven for those inside and outside a movement to consider and try-on certain social and political ideas. A survey of activists in 2001 found that “the very act of singing may in some cases facilitate recruitment by enabling people to express certain ideas out loud that they are otherwise afraid to voice — and hear themselves doing so,” which allows listeners to “weave what they feel the artists are saying into a web that ties their own personal lives to greater social ideas and collectivities” — a kind of bridge between Peter Dahlgren’s common and advocacy domains of the public sphere. The breadth of discussion within the YouTube sample suggests that social media now has subsumed much of that role. Still, the posted songs provided the reasons for arriving on the pages where the discussions took place. The songs also framed at least the initial subject and tone of those comments. Come for the tunes, stay for the trolls.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed