|

I just returned from Denver, where my best friend David and I saw Morrissey in concert at Red Rocks. I’d intended merely to wax nostalgic about this — we’d seen him on his first solo tour in ’91, also in Denver, and I’ve much to say about how rewarding it’s been to grow old with Moz — but something he did at the end of his show makes for a poignant follow-up to my previous ramblings about the evolution of protest music performance. The Red Rocks setlist was a hit-or-miss affair, no doubt. After a slow start with the anemic melodies of “Suedehead” and “Alma Matters,” it took the drive-by B-side of “Ganglord” and its accompanying video imagery of police brutality (to man and beast) to remind us that this was a performance by a man who’s always had something very sharp to say about society. Granted, Morrissey’s emotional side has matured beautifully on recent records — his performance of “Kiss Me a Lot” at Red Rocks was one of the evening’s loveliest — though his latest band lacks the finesse to prop up his earlier heartfelt fumblings (“What She Said” was a muddy morass). But Morrissey has remained a valued and valuable poet because of the maintenance of his core value: being unlike the mass of “lock-jawed pop stars / thicker than pig shit / nothing to convey” by conveying a great deal. He addresses this work ethic in his Autobiography: “It was never a question of becoming a pop singer, more a matter of entering the field of argument.” Indeed, “buying a Morrissey disc remains a political gesture,” as it should be. Building on the aforementioned Live Aid discussion, such outspokenness (ironically?) is what that concert’s organizer, Bob Geldof, later pleaded for in modern music, sounding very Morrissey-esque in his 2011 keynote speech at SXSW, bemoaning, “Everybody’s got the means to say anything they want, but nobody has anything to say,” then pleading with young musicians: “Say something to me!”

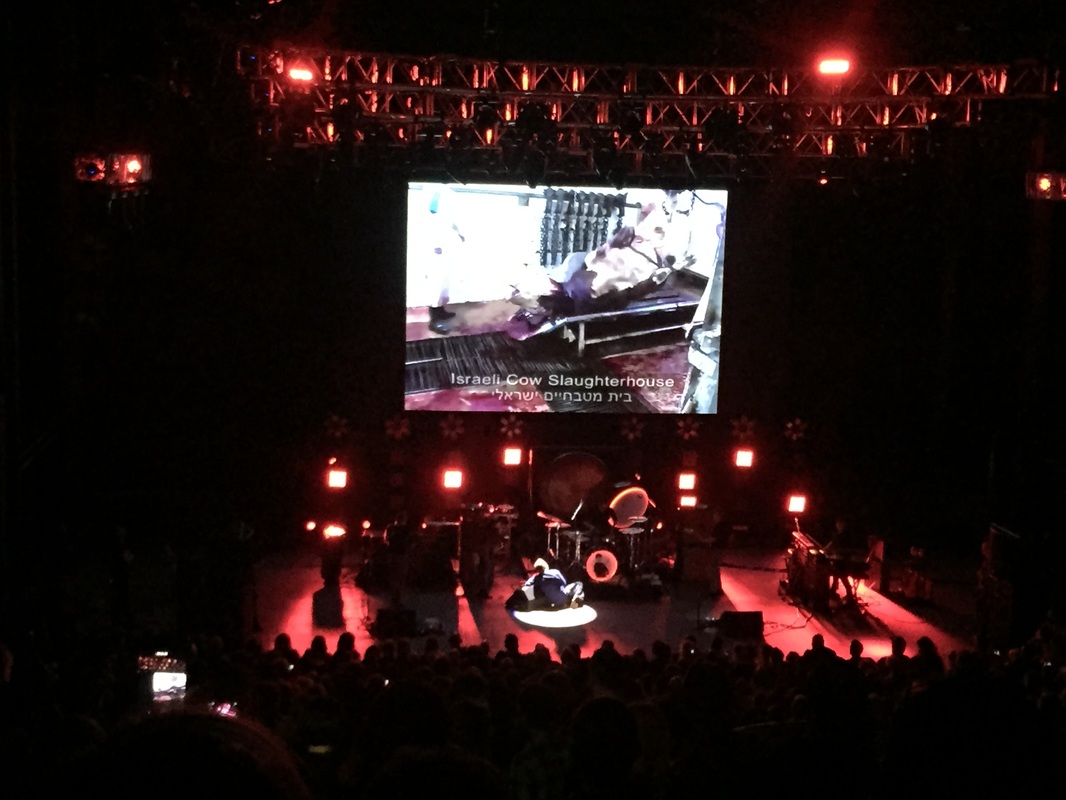

Morrissey still has plenty to say, and his records thus far have remained timely and eloquent. On this tour, however, he abandoned any microscopic crumb of tact he might previously have possessed in order to hammer home his most personally important message: that the killing of animals for meat is morally wrong. This comes through, unsurprisingly, the title track to his 1985 album by the Smiths, “Meat Is Murder.” Near the end of the concert at Red Rocks, as throughout the tour according to other reports, Morrissey eased into the deceiving ballad with a mustardy relish. As the song lumbered to life, video was shown of animals being summarily beaten, tortured, and indeed murdered in various food-factory slaughterhouses. It is, purposefully, difficult to watch. Others my age may recall watching bootlegs of the “Faces of Death” snuff documentaries in the ’70s and ’80s; this footage reminded me of that discomfort. Morrissey spewed his spittle, then reclined on stage facing the screen (pictured above), watching along with us the deeply disturbing footage — which seemed to go on and on, no doubt intentionally elongating the impact. The footage ended with a single title card and a significant challenge: “What’s your excuse now?” It was a shocking move, even after all these years, and an effective one — both positively and negatively. As entertainment value, the performance absolutely deflated the concert. Much of the audience around us was left utterly bereft, even seemingly a bit miffed at having been subjected to an experience other than a continued opportunity to worship both their musical godhead and their own soggy nostalgia. How, after all, do you follow that? (Morrissey followed it with one final number, “Now My Heart Is Full,” a song that seemed just enough of an emotional rescue but that could also be read as perfect punctuation for the previous provocation — I’ve said my piece, my conscience is clear.) Then again, it also worked. The song — and its subject — was the talk of everyone within earshot filing out of the venue, of the dozen people on our shuttle bus all the way home, and between David and I for days. I even posted about it on Facebook, seeking guidance from vegetarian friends on how to ease the dietary switch. I’d eaten a burger for lunch before the concert, and I felt terrible. Here’s the thing: I didn’t feel bad for the cow, I felt bad for me — and this is the crux of Morrissey’s approach to poetical protest. A great scholarly book, Gavin Hopps’ Morrissey: The Pageant of His Bleeding Heart, asks what, if anything, Morrissey has used his music to protest for. His answer is complicated, but the gist of it is that “Morrissey was heroically standing up for humanness” (17). Because it’s not necessarily the animal that suffers most in the industrial food supply, though of course it does and dies; rather, it’s humanity’s character and soul that shrinks through any act of murder, whether we actually commit it or (as is the case for most carnivores) are simply complicit in systematizing it for our alleged benefit. Morrissey’s unflinching performance firmly held his ground on the field of argument and was, for me, a subjective reminder of protest music’s potential potency.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed