|

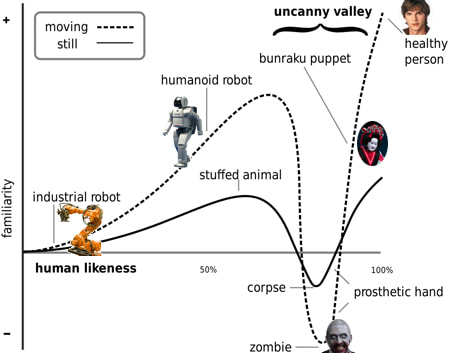

I think I possess the very opposite of a macabre personality, but I’m thinking a lot today — in grave detail, shall we say — about my father’s corpse. Dad would have been 78 today, having died eight years ago. On that occasion, his lifeless body was displayed for viewing at the funeral home, per the Western custom. It’s one of life’s most uncanny experiences, a viscerally unsettling moment that drives home exactly why the corpse is a violently othered item labeled at the bottom of Mori’s uncanny valley (chart above). I only braved it in order to slip one of Dad’s favorite cigars into his suit pocket. Approaching the body, though, was plainly terrifying. Waxy, rigid, no sign of his trademark (and inherited) fidgets, he looked vaguely like Dad but was definitely not Dad. Some part of me, both hopeful and dreadful, was certain he’d open his eyes and yell, “Boo!”  In the preface to Margaret Schwartz’ excellent study of corpses as media, Dead Matter: The Meaning of Iconic Corpses, she describes a similarly unnerving posthumous encounter with her own father: “The trauma of the corpse was the coincidence of familiarity and otherness — the undeniable sense that this loved someone is irrevocably elsewhere and otherwise. The embalmed corpse was an abomination” (x). The immediate abomination to me was that Dad was presented as if dead. His very material staging communicated his irrevocable otherness. Schwartz’s book traces the history of this, how the media of both photography and embalming crafted this common presentation of the corpse: lying in repose, eyes closed, as if sleeping. This position best suited the needs of those media charged with communicating meanings of the dead person. What is also communicated in that particular embodiment is that the dead person will not be participating, at least directly, in the communication. Like other preserved, laid-in-state bodies — think Lenin, Ho Chi Minh, Mao Zedong, etc. — they lie as if sleeping, eyes closed, an object present in the space and acting upon and within that space just as other objects do but no longer wielding a willed agency of their own. Silent. Were Schwartz or I to try and attempt to speak with our departed dads, we would be aiming for the other(ed) and privileged side of the Cartesian dualism. The resulting séance would focus on a separate, absent spirit; the body, present or not, would be immaterial, so to speak. But what if I had arrived in the viewing room to find Dad’s body seated, eyes open, a book in his hands? Would the experience be more or less disturbing, unsettling, uncanny? In Western, Cartesian philosophies, the presence of the corpse communicates a kind of telepresence. The spirit allegedly is the operator of the body. Once absent from that medium, we may continue to think that the spirit might return again to operate through that body, or another body, or other objects. (Small wonder that the modern fields of communication and media studies rest their very foundations upon spiritualist language, from communing to mediums? Thank you, John Durham Peters.) Thus, the presence of the corpse is an aggravation — and a possibility. The presence of a living body is powerful, so much so that a dead body continues communicating a degree of its former subjective presence. The aforementioned autocrats (or their followers) attempted to harness this power and wield it through the preservation, display, and continued upkeep of, for instance, Lenin’s body. It’s not long before that task transforms and any posthumous subjectivity finally vanishes from the corpse, replaced by state-supporting symbolic power or mere material agency related to actor-network theories. If the corpse, however, could rematerialize into a seemingly functional body — could be reanimated — the potential for increasing the length and power of that presence effect might be boosted dramatically. Now this post is beginning to read as if I’m about to propose changing the poles "from plus to minus and minus to plus" a la Young Frankenstein (“It! Could! Work!”), but it’s really just a grad student working through some concepts about the digital resurrections he studies — hologram simulations of deceased pop stars, like the Tupac hologram, Michael Jackson's posthumous performance, the upcoming world tour of the late Ronnie James Dio — on his way to exploring more historical examples of such efforts (not only to maintain the presence of a dead person but to keep some form of the body earning for the estates). Specifically, I’m preparing to visit with Jeremy Bentham, who’s been dead nearly two centuries. Bentham, the famed British legal philosopher and architect of utilitarianism, died in 1832, but his body remains on display at University College, London. Unlike Lenin and the others lying in repose, Bentham left strict instructions for a different mode of posthumous bodily preservation. In his will as well as in an extraordinary pamphlet titled Auto-Icon; or, Farther Uses of the Dead to the Living *, Bentham dictated two uses for his earthly remains. First, his body was to be dissected publicly by medical students. The “publicly” is important: in the early 19th century, human dissection was deeply feared and widely prohibited. Seeking to rout religious influence from all corners of social life, and recognizing the benefit to anatomical study such procedures produced, Bentham hoped one of his last acts on earth would be to assist in chipping away at the taboo by making this practice public. Once that was over, though, the second, stranger task was to begin. Bentham instructed his close friend, the physician presiding (even lecturing) over the dissection, to collect his bones and reassemble them into a skeleton. Bentham’s head was then to be mummified and affixed atop the skeleton. The effigy was to be stuffed, dressed in one of Bentham’s suits, positioned at a desk, and displayed, also publicly. Other than some slight snafus (the preservation of the head rendered it unsightly, so a wax replica was made instead) this is what happened, and the resulting “auto-icon” sits in a chair, holding Bentham’s old walking stick, inside a glass case on the campus (above). The result of Bentham’s bequest interests me far less than its original idea as outlined in the Auto-Icon text. Something distinct and important happens in the move he makes from first suggesting public dissection (a perfectly utilitarian idea) to then suggesting that the sweepings be dressed up and displayed. Where is his utilitarian “greatest good” (and for how many) in the iconization and, as he suggests, veritable veneration of the dead body? I get that Bentham is having us on, but only a bit. Most texts about Auto-Icon refer to its humor, irreverence, its tongue firmly planted in cheek. However, you can tell that he’s somewhat serious in the portions of the text where he lingers over certain items from his list of potential uses for dead bodies preserved in this manner. He goes on at length, for instance, over his suggestion that the auto-icons of deceased philosophers be corralled into public, staged performances — dialogues of the dead — which could be animated by offstage voices and children strapped to the corpses in order to make them walk and appear to talk. (In terms of contemporary technology, that would be adding motion-capture and voiceovers to a digital representation.) He wants to be the head, literal and figurative, of a Hall of Thinkers (think the Head Museum in “Futurama”!) that begins with him. He really wants to be preserved — in posterity (which James Crimmins likens to Comte’s positivity), and given his views on embodied identity and the negation of spirit the only way he thinks he can live on in posterity is on his actual posterior. One of the theoretical limbs I’ve been creeping out onto is the idea that the auto-icon — the potentially animated corpse body and the presence that it may communicate — is itself one of the fictitious entities Bentham wrestled with in trying to streamline language for accessible legislation. Through C.K. Ogden’s analyses of Bentham’s legal thinking, I understand that Bentham initially was frustrated by fictions present in the English language (“Suppositions, Theories, Assumptions, Hypotheses, [and] Fictions” [25]), namely metaphors and idealistic phrases that had no real/physical referents, and that eventually he had to conclude that such components were necessary for thorough communication. When Bentham writes about the necessity of “a multitude of imaginary beings, all spoken of as if they belonged to the class of bodies or substances” (quoted in Ogden 1993, 24), he’s basically claiming that the perceived reality of our discourse requires some augmentation (like adding digital content to physical reality via augmented-reality tech) lest we speak only of things that exist and never of ideas. The “imaginary beings” are necessary to communicate at all. (Again, paging Peters!) In his tug-of-war between words and things, Bentham leans hard on referents and antecedents, presaging semiotics and a good chunk of modern communication theory. “When an unusual word presents itself, we challenge it; we examine it ourselves to see whether we have a clear idea to annex to it; but when a word that we are familiar with comes across us, we let it pass under favour of old acquaintance” (quoted in Ogden 1932, xx). The same might be said of objects and bodies. When an unusual or somehow unsettling body presents itself, and we find we have no clear idea of it, we let it pass under favour of old acquaintance. When we see a figure on stage that is billed as Tupac Shakur, looks like Tupac Shakur, moves like Tupac Shakur, and sounds like Tupac Shakur (quacks like a duck, as it were), we don’t interrogate its reality with the same ferocity as something new and unfamiliar because we have an existing association with who and what Tupac is. (Beautiful, too, that Bentham uses the verb “pass,” as a future post here will explore my connection between the uncanny valley and literatures of passing, i.e., for a different race, gender, class, etc.) Thus, frequently “mere fictions are in abundance regarded as realities” (quoted in Ogden 1932, xxviii). Fictional things often are accepted as if they are real — ask any propagandist — and it’s the “as if” that seems to be the important conceptual “a-i” for the actual “auto-icons.” Bentham, interestingly, was tormented by ghost stories as a youth. No doubt psychologists could make something of that as a motivation for his drive to exorcise fictitious distractions from public life and law. In the end, his auto-icon project sought to create a different way the living could be present with the dead — a rational means, free of superstition and religion. Posthumous presence without piety! Better the devil you know than the one you don’t; likewise, for Bentham, better the dead person you can visit and see than the one that might be hovering invisibly behind you. Bentham sought to capture and utilize whatever remaining subjectivity and agency the corpse might wield to replace eternal reward (or otherwise) with material presence and posterity. So, at the risk of being too absurd and possibly morbid: yes, the figure of my father’s body seated as if he were still alive would make for, I think, a far less traumatic final visitation. An auto-icon would land slightly above the actual corpse on Mori’s chart, remaining on the solid line representing still objects and bodies but closer to where that line intersects with moving, animated ones. The corpse laid out as if asleep and dead violently others the body, which can serve certain powerful interests. An auto-icon, on the other hand, cushions the othering process, freezing a moment of life and crafting a material carry-on that extends certain aspects of communicative presence for a period of time after death. Whether that holds true for digital representations is still to be determined — stay tuned for an inevitable response post to Marjorie Prime next month! * Bentham's Auto-Icon text is surprisingly hard to find. His final text, it was suppressed slightly after his death; some of the propositions are that outrageous. Dig it up now in James E. Crimmins' Bentham's Auto-Icon and Related Writings, Bristol: Thoemmes Press, 2002.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed