|

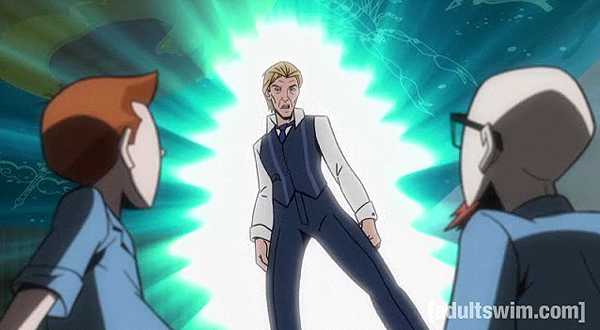

Reports of David Bowie’s death had been exaggerated since the turn of this century. Even before his 2004 collapse on stage at a music festival in Germany, which resulted in an emergency angioplasty to clear a blocked artery, his penchant for keeping to his adult self fueled more-than-occasional rumors about his earthly condition. The Flaming Lips went so far as to title a 2011 joint single with Neon Indian “Is David Bowie Dying?” When he finally popped up in 2013 to debut a new single, fans overlooked the song’s maudlin nostalgia out of simple relief that he was alive and working. Tony Visconti, meanwhile, kept assuring us, “He’s not dying any time soon, let me tell you.” Would that it were true. How could Bowie die, anyway? Surely there was no messy mortal at the center of all that radiant expression of life. Surely he was just a manifest Foucaultian process, an anthropomorphized discursive object, never actually material. At most, should the time come, he’d simply act out his departure as depicted on “The Venture Brothers” — saying, “Gotta run, love,” changing into an eagle, and flying away. When the news arrived on Monday, reality bit. As Bowie sang in the title track to his “Reality” album, “Now my death is more than just a sad song.” I wasn’t even the biggest Bowie fan in the world, not by a long shot, yet it was hard to concentrate for the rest of the day. Bowie the fountainhead flows through so much of the cultural landscape; I am the biggest fan of many folks who wouldn't have had careers, wouldn't have had the courage, without the lifeblood of that flow. Watered by his life, droughted by his death. I sat in my campus office, trying to work while listening to “Blackstar,” and a creeping dread arrived: How am I going to explain Bowie to my students? In my first class, I asked, but I knew: A few confessed to knowing who he was, but no one was a fan. No one had found him. I asked who their Bowies were, who had presented them a new worldview through art; they named actors and (!) race-car drivers, no musicians. Swallowing my personal astonishment, I probed the reasons: “music’s everywhere,” “music’s free.” Aye, the pirate’s grin. I tried not to proselytize, tried not to come on strong and turn them off. Every class of undergrads potentially contains that one kid who really needs a Bowie. The archetype usually nervously pipes up when the syllabus steers into gender performativity. I read aloud the widely circulated paragraph from Caitlin Moran’s essay, “10 Things Every Girl Should Know”: When in doubt, listen to David Bowie. In 1968, Bowie was a gay, ginger, bonk-eyed, snaggle-toothed freak walking around south London in a dress, being shouted at by thugs. Four years later, he was still exactly that — but everyone else wanted to be like him, too. If David Bowie can make being David Bowie cool, you can make you cool. Plus, unlike David Bowie, you get to listen to David Bowie for inspiration. So you’re one up on him, really. YOU’RE ALREADY ONE AHEAD OF DAVID BOWIE. We live in a post-gay, post-racial world, right? (sarcasm, ahem) And yet that statement still squeezes the lower lobes of my wheezing old heart. Most of what we’re discussing in this term’s intro-to-comm class, I assured them, could be discussed through the lenses of Bowie’s art, and I encouraged them to do so. Students brought up the relation of visuals to music, how that was becoming more predominant as Bowie emerged and how he capitalized on it. We talked about personas, the performance of self — like what we do every day on social-media platforms, via avatars that potentially can be as radical and boundary-pushing as Ziggy. We talked about combining musical genres; one of them called Bowie the first real mashup artist. (I refrained from running to the chalkboard a la “A Christmas Story”). We talked about media systems, about how anyone would actually discover and promote a new Bowie today. Another bonk-eyed genius might be out there right now, posting into the YouTube abyss. How will we know? They were leery, of course, and they should be. One of the reasons I never became as devoted a Bowie fan as my best friend did was because of the same generational skepticism that caused my students to hesitate before even my measured assurances of Bowie’s importance. When I was young, all those boomers insisting of his mastery — I just cranked up my Smiths cassette, oblivious to the connections. In his Autobiography, Morrissey recalls how “Bowie’s extraordinary effect of menace upon British culture is largely forgotten now, but I watched it break like a thundercloud in 1972, and its presence was a volcanic as that which later would be termed Punk.” Perfect word choice: menace. Remember when Bowie was a real threat? However we work through the meaning of his death — and there’s great scholarship about celebrity death, namely Steve Jones’ “Better Off Dead: Or, Making It the Hard Way” in the excellent book Afterlife as Afterimage: Understanding Posthumous Fame, edited by Jones and Joli Jensen — the consensus is clear that now, as in life, Bowie was an Important 20th Century Artist. This hasn’t been understated thus far in the countless tributes gushing forth from a surprising variety of voices. Every angle has been or will be examined, including Bowie’s commentary on the anxiety of science fiction, a well-deserved focus on Bowie the songwriter, an expectedly fun recounting of his insane year in L.A., some really bizarre summations (“His death is the capstone on the pyramid of necrotic Anglo-American mass culture”), even two, count ’em two, appreciations of his innovations in the field of finance. I steered my students into a discussion of media systems, about why individual icons were more easily manifested and wielded power in a pre-Internet era. Bowie, of course, was way ahead of me, explaining in a really good 2000 interview with the BBC how music was evolving away from celebrity control, that pop was becoming more about “subgroups and genres” and transforming into “a communal kind of thing.” “It’s becoming more and more about the audience, because the point of having somebody who led the forces” — at which point he raises his fist and smiles — “has disappeared, because the vocabulary of rock is too well-known now. It’s only a conveyor of information, it’s not a conveyor of rebellion.” This was no complaint, mind you. Ever the surfer of evolution, Bowie followed with: “I find that a terribly exciting era.” Tony Visconti, again in 2013: “He couldn’t have done two years’ work if he was a sick man.” He was referring to “The Next Day.” Now we know that “Blackstar” — Bowie’s 25th album, released on Friday just days before he died — was recorded during the last year and a half of Bowie's life, under the full weight of his illness and its unavoidable outcome. Watching the video for “Lazarus” — knowing now just how unusually literal the imagery and lyrics are — is gut-wrenching. “Ain’t it just like me,” he sings, choreographing his own death. The imagery ends with Bowie, in a black-and-white leotard, backing into a dark armoire and closing the door. Now we await the surprise comeback tour, of course, with Andy Kaufman opening the set. Meanwhile, I dread the perhaps inevitable announcement of a Bowie hologram resurrection. (To my surprise, I just learned Bowie’s already been a hologram once — in a video game).

Monday night, I found myself sitting in a Science Studies colloquium, enjoying a wonderful presentation by Janet Vertesi about her studies of space-mission science teams. She mentioned, in explaining the depth of her ethnographic embedding, that she had attended weddings of the scientists and even a funeral for one of the robot crafts. During Q&A, I demanded to hear about the robot funeral. It was a technical object, but it represented — no, it was — the work, the human expression, the earthly angst of so many humans, the humans themselves. When it failed, it deserved the ritual send-off. I drove home, and “Space Oddity” came up on my funereal selection of playlist. Bowie again saying goodbye (he did that a lot), but at least he’s not lost — his “spaceship knows which way to go.” We ache, we call after him, but again, reality: “There’s nothing I can do.”

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed