|

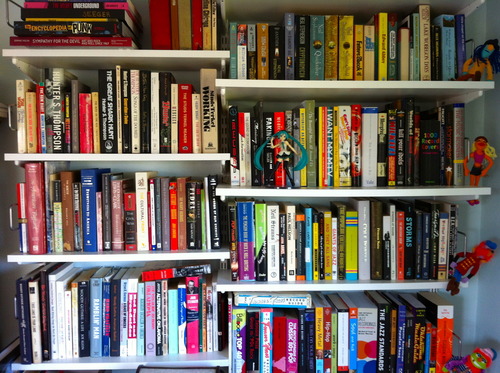

Life is great like this: I spent an afternoon this week unpacking the remainder of my library (delayed, as often happens, months after moving in), and basking in the intense comfort of having treasured volumes once again within reach; then, I sat down with a well-earned cocktail and opened Illuminations, a collection of Walter Benjamin essays recently added to my to-read shelf — and what to my wondering eyes should appear but the anthology’s first selection: “Unpacking My Library.” Benjamin is a figure I keep bumping into in graduate studies, and someday I’ll tackle his mammoth Arcades Project (for all I’ve ever really wanted to be in life is a flanêur), and I find him intriguing as a complex man and a down-to-earth theorist. “Unpacking My Library” is a rich treat on both fronts, interesting ideas from an obviously interesting person. A speech to fellow bibliophiles, these remarks celebrate the fastidious privacy of the (bourgeois) collecting habit. “I am unpacking my library,” he opens, adding, “Yes, I am” — this second sentence not confirmation of fact but breathless celebration among those he knows will share in the revelry. It’s a relief of reunion with not texts as much as objects and the memories they transmit, like beacons. It’s all about memory, for Benjamin, this gazing at crates and shelves:

Every passion borders on the chaotic, but the collector’s passion borders on the chaos of memories. More than that, the chance, the fate, that suffuses the past before my eyes are conspicuously present in the accustomed confusion of these books. For what else is this collection but a disorder to which habit has accommodated itself to such an extent that it can appear as order? (60) Paging Miss Marchmont (“I love Memory to-night …”)! Public objects are hoarded for purely private means, resulting in a private collection to which the clearest map is visible only to the individual collector. The public worth of a private collection, Benjamin says, is basically not much. In fact, once a private collection goes public, something is lost — a challenge familiar to those with experience in archives, where some contextual explanation necessarily precedes a researcher’s exploration. Benjamin adds that “the phenomenon of collecting loses its meaning as it loses its personal owner. Even though public collections may be less objectionable socially and more useful academically than private collections, the objects get their due only in the latter” (67). This rings true for me, twice. While reading Benjamin’s book-induced reverie, I empathized not only within the freshness of my study’s own musty odors — I also began mentally substituting the word “books” for the word “records.” Music collectors likely would find this piece equally comforting. Half the joy of thumbing through my albums springs from the memories of their general pursuit and specific discoveries — that unknown, third Whipping Boy album I found at that cramped shop along the south bank of the Liffey, the Denzil record finally purchased after the unheralded wunderkind’s poorly attended club show during a lightning storm in Tulsa, the live Lloyd Cole B-sides that made two hours’ digging in the basement of New Orleans’ Record Ron’s worth every dust-choked minute. Benjamin knows this thrill: I have made my most memorable purchases on trips, as a transient. Property and possession belong to the tactical sphere. Collectors are people with a tactical instinct; their experience teaches them that when they capture a strange city, the smallest antique shop can be a fortress, the most remote stationery store a key position. How many cities have revealed themselves to me in the marches I undertook in the pursuit of books! (63) Of course, in the end — and musicians know this drive, too — Benjamin advises: “Of all the ways of acquiring books, writing them oneself is regarded as the most praiseworthy method.” Not only that, the drive to write is not most valiantly pursued with the desire to, God forbid, express oneself, but to fill the void in one’s collection — to write the book (make the album) you simply haven’t found to fill that certain spot on the shelf between ideas. “Writers are really people who write books not because they are poor, but because they are dissatisfied with the books which they could buy but do not like” (61). Sometimes, you just have to do it yourself. Be it resolved for this new year!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed