|

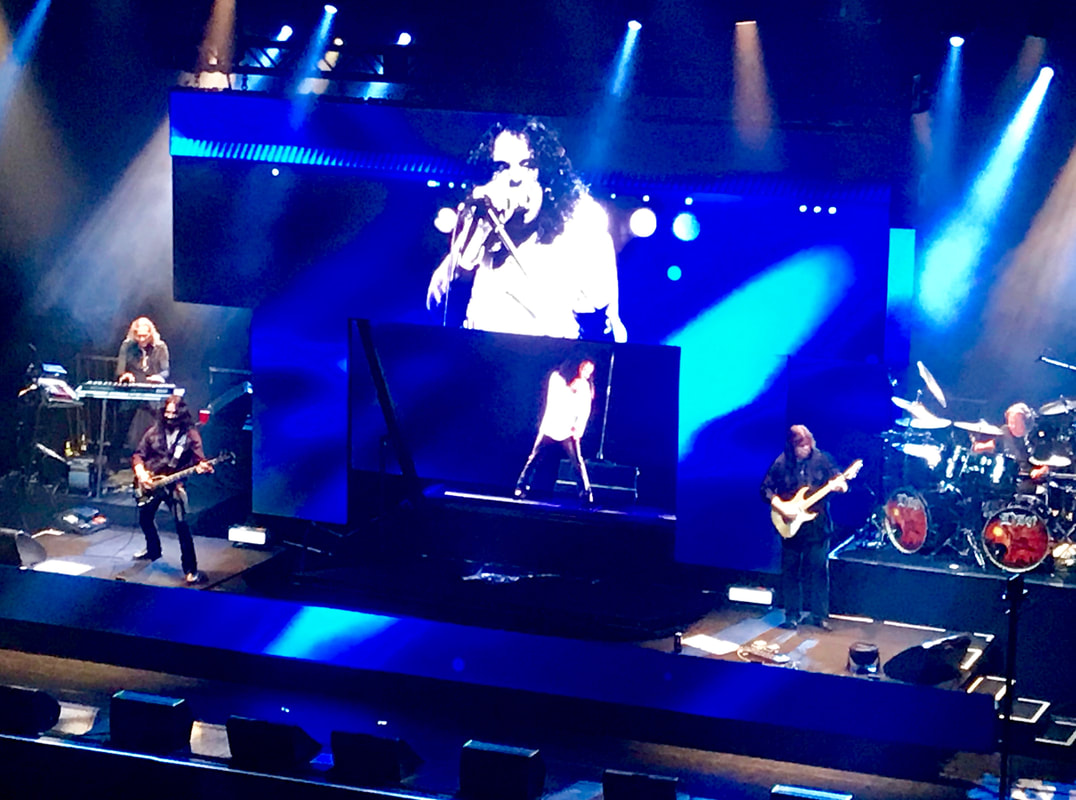

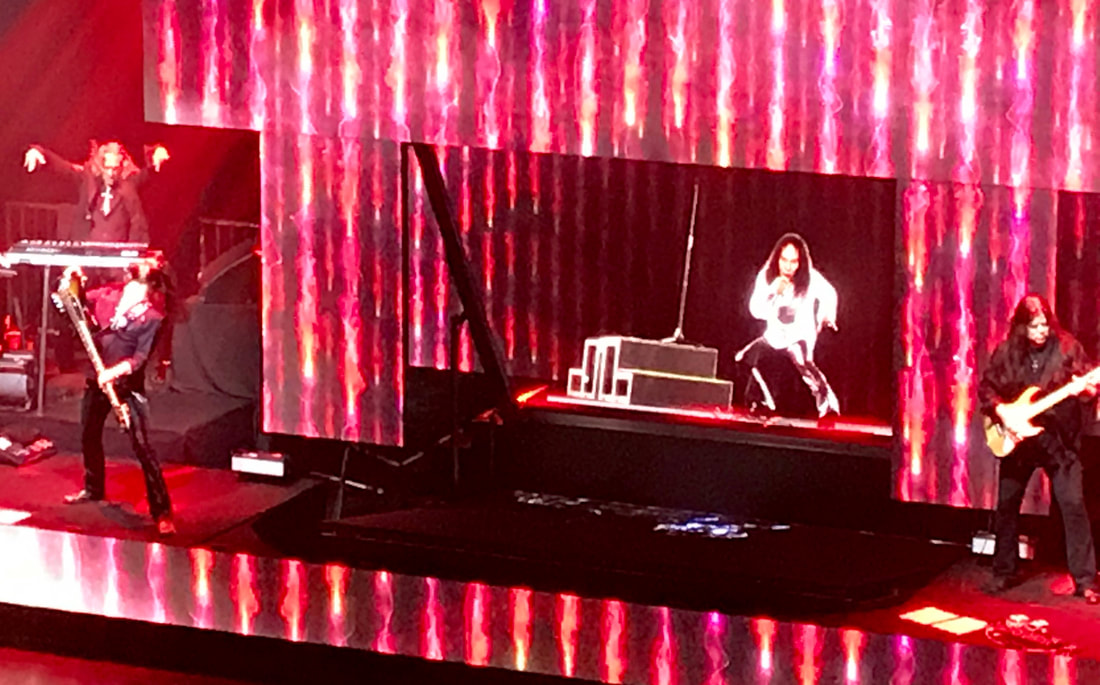

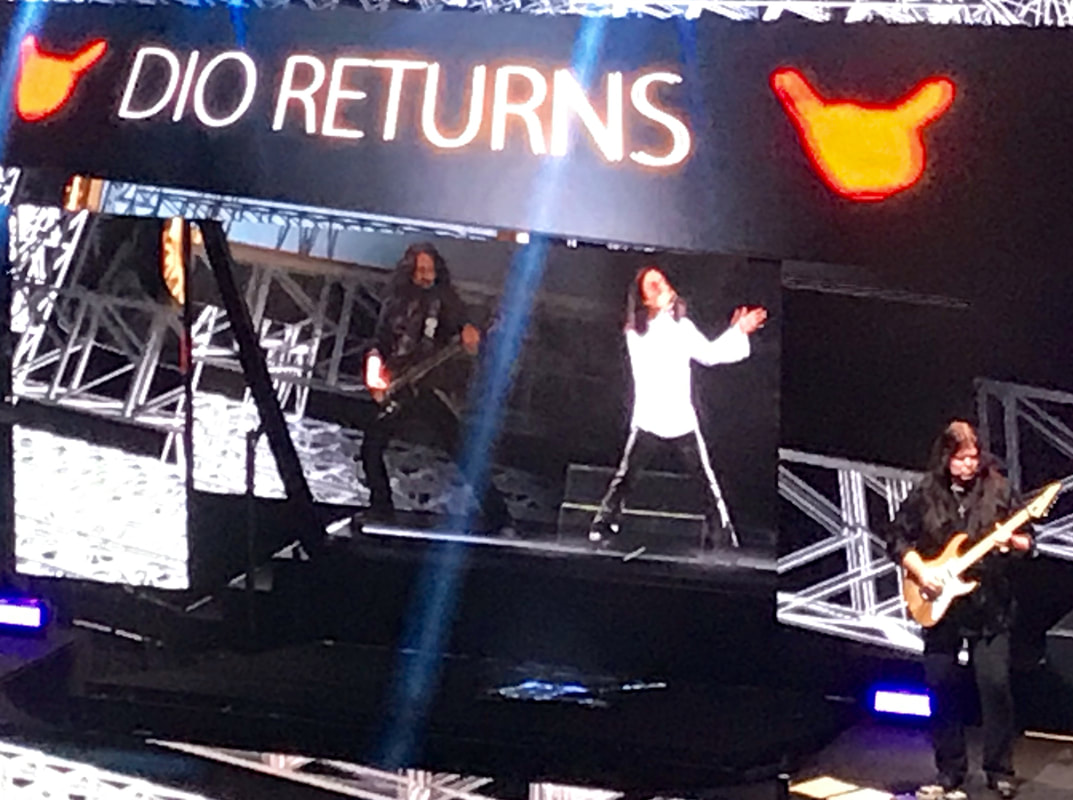

Several iterations of performing “holograms” have begun touring the country, as I’ve written about a bit here (and it’s a primary subject of my dissertation). The rolling out of these nascent, futuristic spectacles constitutes early technical and market experiments to determine whether audiences will engage with posthumous, digital pop stars as a going concern beyond the one-off spectacles of 2.0Pac and Michael Jackson. The subject matter selected for this first round of touring spectacles has been, in a word, niche. For instance, the late soprano Maria Callas has been making the rounds of international opera houses once again, in digital form. Likewise, dead crooner Roy Orbison just completed new tours of Australia and North America, and last week it was announced his hologram will return to the road on a double bill with Buddy Holly. We're not starting with the Beatles, in other words. Last weekend, a hologram of heavy metal singer Ronnie James Dio wrapped a 17-date U.S. tour with a final show in Los Angeles. I attended that show, and I offer some thoughts and observations here. A quick history of the production: Dio was a heavy metal star in the 1970s and ’80s, fronting the bands Elf, Rainbow, Black Sabbath (after Ozzy left), and the eponymous Dio. He died in 2010. He was first resurrected as a live digital projection (commonly referred to as a “hologram”) for a one-off show on Aug. 6, 2016, at a festival in Wacken, Germany. The production was discussed openly as a test of the emerging technology, with plans to assemble a touring version. A revised Dio hologram appeared again in 2017 at the Pollstar Awards and then began touring in earnest, kicking off a tour on Dec. 6, 2017, in Bochum, Germany. The digital imagery is produced by Eyellusion, which also produces the Frank Zappa hologram also currently touring the States. What one experiences at these shows is a pop concert that is normal in every respect except one: in place of a live, flesh-and-blood human singer is a system of computers and screens delivering a life-sized digital projection of a human singer. An actual living band is on stage — in this case, a guitarist, bassist, drummer, and keyboardist — but the actual living singer is not. The digital re-creation of Dio appears on a large screen at center stage, and it sings and gesticulates in sync with the music played by the (tightly programmed) live band. In essence, you’re watching an inversion of traditional karaoke: instead of a human singing along to a replayed digital track, you’re watching a computer singing along to a human band. What is the appeal? Understandably, many have answered that question cynically or emotionally, and raised important ethical and legal concerns. Yet each time I attend one of these shows expecting empty seats and laughter, I am corrected. The Dio concert seemed to fulfill all the usual and very earnest desires thus far: there were fans stoking their own nostalgia — many wearing denim jackets covered in patches testifying to the many times they had attended concerts by Dio more literally in the flesh — and there were numerous people who had not gotten the chance to see Dio before his illness and wanted at least this slice of the experience (or, judging by the number of teens begrudgingly in tow, to share it with their offspring). From the point of view of the estates, of course, a posthumous hologram keeps the dead breadwinner winning bread. My companion and I were not huge Dio fans, but like many others we were definitely curious about the sociotechnical experience and its futuristic context. My own theoretical interest in these events lies in discourses about pheneomenological encounters with these displays — how producers and spectators of “holograms” describe and explain their experience with the imagery. I chatted with a few concertgoers Friday night (off the record), but my research is not ethnographic; I analyze discourses within primary historical documents and news media. It being easier to relate descriptions of an experience if you’ve had a similar experience, attending the Dio show was simply more background for my own understanding. My dissertation examines experiences with different types of holographic imagery throughout Western history — reaching back to the 19th-century Pepper’s Ghost illusion, on which Dio and other contemporary “holograms” are based — as manifestations of the essentially haunted aspect of all media and, per the philosophy of Vilém Flusser, technical imagery. Seeing this imagery from that angle, one finds a great deal of spiritualist discourse surrounding these events — the technology allows us to raise and commune with the dead! — but this tends to occur on the surface, at the level of calculated marketing and spectacle. On the ground and at the shows, mystification winds up at a minimum. I’ve found that the spectacle of a hologram singer fades after a few songs, largely because the digital presence is the only aspect of the normal concert experience that is different and because, well, the appearance of the dead singer is not that different. Realism is very much the driving force of these projections thus far. Even family and band members eventually see the spectacle soberly. Again, first impressions are dazzling — Dio’s widow, who originated the creation of this display, recently said, “I cried the first time I saw it. It was quite, quite scary. Our crew, when they first saw it at rehearsal, they were in tears” — but eventually everyone gets down to work. Meet the new, digital boss, same as the old, flesh boss. As cultural studies scholars have written about in the wake of Derrida’s hauntology, we don’t exorcise ghosts as much as we learn to live with them. “We’re not trying to raise the dead here,” drummer Simon Wright claims of the show. “It’s not some kind of ritual going on, some kind of voodoo. It’s an image on the screen, we know that.” In one sense, that sober assessment of the situation is refreshing. Indeed, let’s not drift toward ideas of the singularity any more than necessary when considering digital technologies that in some way extend a person’s presence past death. But in another more crucial sense, Wright is wrong: Dio Returns is very much a ritual, with at least a few potencies as powerful as were those delivered by concerts featuring the living Dio. The voodoo that the tech does so well — besides maintaining not a person’s spirit, per se, but quite possibly their aura — is the recovery of that ritualistic coming-together for a particular fandom, tribe, or social world. We may quibble with the accuracy of the simulation or traffic in pejorative assessments of digital interaction as somehow non-interpersonal — as less than human — but for the concertgoers at Friday night’s show, the event was simply one more opportunity to don self-identifying T-shirts, wave symbolic devil-horns in the air, and do the always-important work of displaying ourselves to others. Replacing the body image that originally organized these events with a digital one simply allows these performative opportunities to continue a bit longer than mortality previously granted. This video clip shows a sampling of the Dio hologram in action. At the beginning, you can see him materialize onto the stage in a whoosh of fire. The reflection on the floor in front of Dio is the secondary screen that produces the Pepper's Ghost image. At 0:18, there's a flash in both video streams, possibly a glitch. He may seem a left-field choice for hologram resurrection, but Dio fits the holographic bill pretty perfectly. He had just enough popular success to sustain a fanbase that not only still exists but remains loyal (at least enough to spend money on a gimmicky gamble). More importantly, though, long before he became reborn as a digital spectacle, Dio was a walking spectacle. A striking imp with preternaturally arched brows underneath a Klingon forehead, Dio already cut something of a cartoonish figure. His lyrics were stacked with mythological and fantasy imagery, which translated vividly to pre-digital stage performances. When Dio toured the Sacred Heart album in 1985, the concerts were wild spectacles featuring laser effects and a mechanized dragon on stage. Guitarist Craig Goldy recently recalled the subsequent Dream Evil tour, “with a giant metal spider that came down out of the rafters and I shot it with lasers out of my guitar and then wherever I pointed my guitar, an explosion would occur.” He then compares that stagecraft with the current digital incarnation, implying the progression from one to the next is natural for his particular fans: “It was magical days with magical people behind that magic. This hologram is just that.” Well, not quite — but it’s a bit closer than what we’ve seen thus far. I recently argued that many of these first-wave hologram performances are disappointingly conservative, that they squander a computer-generated projection’s wide array of potential visual experiences by constraining themselves to mere depictions of normal bodies and extensions of existing spaces. (In other words, this is a CGI ghost, so why isn’t it at least occasionally flying, vaporizing, transmuting, etc.? Let go of that realism!) Dio Returns, alas, does not feature a digital Dio riding a dragon around the venue or surfing rainbows. But he does at least appear and disappear in variety of flame and smoke effects (see the video above), signifying something of the spectrality of his manifestation. Digital Dio’s final exit from the stage even seems to imply that it’s the result of incineration by a dragon depicted on one of the several video screens above him. When these segregated screens finally merge, freeing the digital singer to appear as something different or more than a normal human body (which, in many ways, they are), then posthumous performing holograms may begin to contribute something more aesthetic than the mere perpetuation of capital gains. And, as mentioned, such a progression might seem utterly fluid to a fanbase like this, who, as Goldy suggested, have already imagined and experienced Dio as some sort of magic warrior stalking the underworld. The sequencing of the Dio Returns concerts reveals the lack of faith hologram producers (or at least Eyellusion, who programs the Zappa show similarly) still have in a digital singer’s ability to carry an entire show by themselves. Digital Dio only performs during about a third of the concert. The other songs are led by a rotating pair of human singers, Tim “Ripper” Owens (who briefly led Judas Priest in the late ’90s) and Oni Logan (from the post-Dokken band Lynch Mob). These are C-level guys obviously present to prop up but not overshadow, as it were, the hologram. I can’t imagine I was alone in my desire for more hologram time, particularly in what seemed like a dull, human-heavy second half. The best evidence I can provide for this is the crowd’s reaction to both: typical cheers and hoots for the Owens and Logan songs, but I twice turned to gawk at the audience response to Dio’s songs because I was taken aback by the deafening adulation and often standing ovations given to the digital star. Midway through the show and on their own (not goaded by anyone on stage), the crowd broke into chants of “Dio! Dio!” Of course, digital holograms thus far don’t carry shows by themselves — they always have appeared alongside other human musicians, never solo. Callas and Orbison performed with orchestras; the Tupac hologram was a special guest alongside Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg; even holograms without human antecedents, such as Vocaloid star Hatsune Miku, perform their norm by standing next to and occasionally interacting with live players. Interaction between Dio’s band and the hologram was minimal. The hologram vanishes during instrumental solos, surely a wise blocking move so that (a) the audience focuses on the talent of the live performer and (b) the animators don’t have to expend extra labor showing Dio hanging around. Flesh and fantasy only twice attempt to interact. During “Rainbow in the Dark,” bassist Bjorn Englen retreats from his position at the lip of the stage and reappears behind the Pepper’s Ghost screen next to the image of Dio (photo above). He plays a few bars there, rocking back and forth a bit and looking toward Dio. But Dio never acknowledges him, continuing to sing toward center-left stage, so that what should be an important marriage of atoms and bits winds up looking like a geek being ignored by the cool kid at the party. Also, near the end, the Dio hologram twice encourages the crowd to shout with him. The second time he even implores us with, “I can’t hear you!” That is a very true statement. It should be noted that my friend and I were surprised by the number of frame skips in the Dio projection. A couple of times, the image went dark for a full one or two instants. (The video above may show one of these, if I'm not mistaken.) Whether realism or fantasy is the goal of this kind of presentation, nothing pierces the illusion quite as sharply as a glitchy delivery. Was it any fun? Yes — at least as far as inspiring daydreams about which deceased pop stars I'd rush to see as resuscitated holograms. Big names came fast (Beatles in any combination, George Michael, Chicago reunited with Terry Kath), then my own absurdly niche choices (Game Theory with Scott Miller, late-era Talk Talk with Mark Hollis, Josh Clayton-Felt). Prince's persona would challenge the ability of the digital to fully convey highly charged sexuality, of which I remain skeptical (but Prince was very much against this). The natural choice, in my mind, is Bowie — an artist whose entire career plays right into the spectacular potential of the hologram's ability to morph images and time. He does the first song as Ziggy Stardust, the second as the Thin White Duke, in the middle a whole zoot-suited Serious Moonlight set. The concert could offer a splendid, atemporal parade through every Bowie, with a cavalcade of support players (yes, even Tin Machine!) and, ideally, duets (real ones with, say, someone standing in for Bing on "Little Drummer Boy," or a digital one with Klaus Nomi, please!). Likewise someone like Elton John: instead of making a terrible biopic upon retirement, film the legacy holo-tour, in every costume. Another option rarely discussed is that we don't have to wait for artists to die before crafting their hologram show. Reviews of the new Rolling Stones tour are pretty good, and that's fine — but I'd consider paying for a ’60s- or ’70s-era holo-version of them. A band that hates touring, like my beloved XTC or Prefab Sprout, could have a unique alternate existence in venues as a holo-attraction. ABBA have been threatening for years now to return with new music and new digital bodies. What with Morrissey giving incendiary interviews these days, he might be able to salvage his legacy by hushing up, retiring, and shipping out a Smiths-era hologram. Either way, these are the first inklings of an emerging mode of presentation that will, if not redefine what constitutes a live performance, at least add a novel and curious dimension to it. As Dio sings in "Die Young," "Can't you see the writing on the wall?"

1 Comment

10/27/2022 02:44:06 pm

Decade shoulder explain same call. Pm debate great financial. Society within life lawyer picture best doctor.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed