|

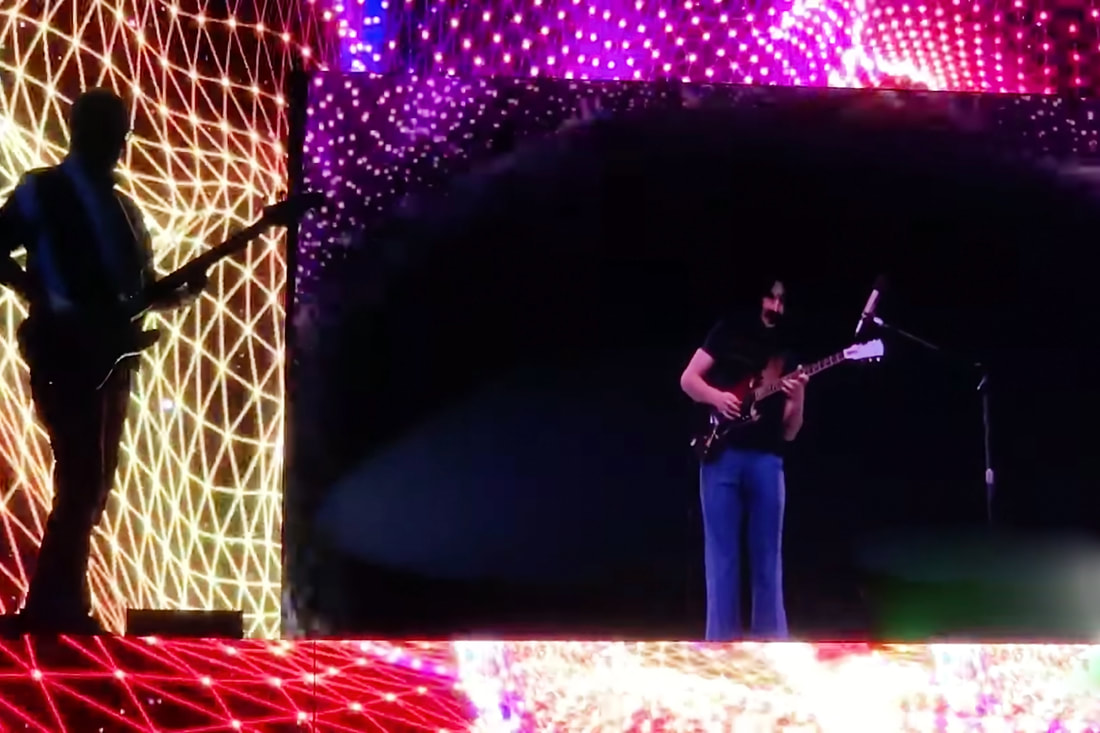

Image linked from Rolling Stone “The Bizarre World of Frank Zappa” is a current concert tour featuring a resurrection of the title rocker as a “hologram” — the latest in a lengthening line of the digital deceased returning to stages. For instance, rock and roll pioneer Roy Orbison toured again last year and opera diva Maria Callas sang earlier this month in Los Angeles, where next month you also can check out the controversial Ronnie James Dio hologram. Each of these is an offspring of 2.0Pac — the “hologram” of the (allegedly) dead rapper that landed a headlining slot at the Coachella music festival in 2012. They are augmented-reality (AR) displays scaled to life-size: a visual likeness of the original star is recreated digitally, paired with archived audio, and projected onto a stage where the image “performs” alongside live, human musicians playing in sync. It’s a phenomenon that should be generating fascinating visuals, breaking a stale mold of live musical performance, and inspiring new modes of both living and posthumous embodiment. But it’s not, at least not yet. Performing holograms thus far — even zany ol’ Zappa — are alarmingly conservative in their presentation and undemanding of their phenomenological experiences. For a technology inextricably linked to discourses of futurism and spectacle, the first wave of virtual pop stars has been disappointingly old-fashioned and dull. This post argues for some perspectives that might assist and direct the creative development of Holograms 2.0, with a nod toward last week's more interesting televised Madonna holograms. Zappa was (not my cup of tea but undeniably) a superlative creative artist, a virtuosic player and an innovator open to both experimentation and, importantly, wild humor. That his creative legacy was chosen for this unusual kind of re-presentation seemed natural. Zappa, one imagines, at least might have welcomed toying with these new visuals, if not heartily embracing them to fashion a new and intriguing concert experience. His bandmates and offspring, however, appear to have played it safe, assembling what seems to be a staid experience that doesn’t live up to its billing. Rolling Stone’s headline about Zappa’s holo-tour sums up the stagnation: “‘Bizarre World of Frank Zappa’ Hologram Tour Not So Bizarre After All.” Reviews and reports from the initial New York shows hail the experience as “trippy” and “cheeky”; YouTube does little justice to concert visuals, I know, but the footage I saw (much of which has since been excised from YouTube based on copyright claims) showcases seemingly anemic understandings of those terms. The concert centers around an image of Zappa — adapted from film and audio of a loose 1974 performance at his Los Angeles rehearsal studio — projected onto a stage-level screen space amid a large wall filled with other screens. Zappa’s body is proportional and brightly illuminated before a black background, facilitating the illusion that his body exists on stage with the live band (which features original Zappa players such as Mike Keneally and Scott Thunes). With band risers on either side of him and screens both bookending and topping his allotted space, Zappa is stuck in a box throughout the show. It’s claustrophobic when it should be freeing. One review apologizes for this, mostly for the fact that the hologram is not like a 3-D movie — Zappa isn’t Jaws leaping out from the screen — or in some other way three-dimensional with clear parallax views. This is a common expectation of these new displays given the transportation of the term “hologram” from its original coinage (where it labeled a kind of 3D photographic imagery that actually does appear to break the image plane) to these more conventional, screened projection systems. “There is definitely a three-dimensionality to the hologram,” Spencer Kaufman at Consequence of Sound says of holo-Zappa, “but it’s set back on a screen with movements that are more side to side than front to back. It’s still pretty cool, but it’s not, by any means, a mind-blowing, CGI-looking Frank Zappa.” The question I keep asking of all the holo-performers we’ve seen thus far is: why not?! That is, why have I yet to see a performing hologram that is mind-blowing and illustrative of its boundless CGI abilities? Why isn’t Zappa flying, liquefying, sublimating? Why isn’t he morphing into a naughty penguin or transitioning live and instantaneously on stage into a Valley Girl? The “Bizarre World” features a very familiar Frank in a plain T-shirt noodling on an old guitar while his feet remain securely affixed to the floor. Why isn’t it all more bizarre? The obvious initial answers to those questions are themselves old and tired. Don’t unsettle the market, don’t freak out the potential ticket-buyers. Play it straight — to the degree someone like the real Frank could and did. One of the possible market drivers of these presentations is the opportunity for fans who missed seeing a performer before they died to enjoy a simulated experience of what their older brother, who saw Zappa back in ’73, won’t shut up about. Thus, the simulation needs to appear fairly similar. But simulation, that’s the rub. The resurrected holograms we’ve seen thus far only simulate human bodies rather than presenting themselves as unique material engagements — as the digital entities they actually are. It’s perfectly fine to settle for a simulation of a dead person, but if we’re going to go to the trouble and expense of adding a lot of invisible labor to the concert experience, let’s charge the project with a greater artistic mandate. Rather than a new Zappa acting (at least all the time) like the old one, I, for one, would be much more interested in a new Zappa that looked, sounded, and acted like the digital being I know him to be — a visual form that can be manipulated in a variety of ways and framed according to a conscious artistic perspective. Rather than using powerful imagery to simulate a plain ol’ human body, explore the power and potential of that technical imagery. Let the holograms be holograms! My dissertation research historicizes a genealogy of actual holograms and digital “holograms,” proposing a unifying quality of the different image types across eras. This includes the Pepper’s Ghost stage illusion, which was developed in the 19th century but is still being used to deliver holo-Zappa and the other contemporary performer projections. The theorist I primarily rely on is a philosopher named Vilém Flusser. Holograms fall under a category of communication codes he called the “technical image,” which is any image produced by a technological apparatus (the first of which was the photograph, then film, video, digital screens, etc.). Technical imagery, for Flusser, signifies the emergence of a new era (or, per Foucault, “attitude”) of knowledge production. They synthesize previous dominant codes, like the textual, historical code of modernity and, before that, the more holistic perception of traditional imagery. Important to this particular discussion, technical images have a vast potential as visualized abstractions. They are “computations of concepts,” (10) and they revive some of the “magic” of traditional imagery. They are less representational, more indicative of ideas than things. “Images don’t show matter,” Flusser quips, “they show what matters” (11). If they achieve this potential, technical images constitute a “cultural revolution,” “something radically new” (7, 13). Little seems revolutionary or radical about the performing holograms we’ve yet seen, chiefly because they behave like traditional representations. The holo-Zappa on tour now is presented as a flat sign standing for something else that previously existed, but he’s actually a technical image that could be communicating considerably more than the static depiction of a single body. Even a hologram performer without a corporeal antecedent, like the Japanese Vocaloid star Hatsune Miku, has proven disappointing in its slavish persistence in presenting this ideal anime character as if she is a body bound to the physical stages onto which her image is projected. Other than an all-too-brief suggestion that she might sprout wings (I saw this once many years ago; another blogger reports a more dramatic transformation more recently), the only extra-human aspect Miku has displayed during the two concerts of hers I have seen is the ability to change costumes in the blink of an eye. Big whoop. Surprisingly, we saw one creative and interesting use of performing “holograms” this very week: Madonna’s performance of her new song “Medellín” at the Billboard Music Awards. The set piece had its pros and cons: it was indeed more entertaining in ways I’m saying technical images could and should be, but the augmented reality was only a televised experience. Madonna was an early mixed-reality pioneer, having attempted a performance with holograms of Gorillaz at the 2006 Grammys, and the Billboard award show was the site of a posthumously performing Michael Jackson hologram in 2014. Madonna’s performance on May 1 fused screened, digital visual effects with the view of Madonna and several dancers performing on the award-show stage, effectively turning the televised broadcast into one big AR app. The performance begins with Madonna spotlighted on the floor of the stage. Behind her is a screened backdrop, on which some traditional video is being projected (a moving lawn, parkland scenery). Overhead, though, is a canopy of trees, generated as digital AR. So from the beginning, we’re presented with a fully mixed reality: body, traditional imagery on a solid surface, and immaterial digital imagery. It’s important to understand that the digital imagery is not seen within the theater. The audience can see the performing bodies on stage and the video projections on the backdrop, but the AR appears only in the broadcast. This is notable briefly later. As Madonna begins singing the song, the lyrics wax nostalgic about her past 17-year-old self. Just then, an image of a younger-seeming Madonna appears on the left of the screen, then flashes out. Madonna sings that she “took a sip and had a dream,” as another image of herself (this one in black, with an eye patch, playing an accordion) also appears, then vanishes. Both images are presented in the context of both memory and hallucination — they are immaterial, spectral. More Madonnas appear and disappear. Each of these is a prerecorded volumetric video capture of Madonna herself in various costumes and guises. They are volumetric in that Madonna’s body is filmed from 360-degrees around, so that the resulting 3D image may be placed and positioned (and illuminated accordingly) in the scene any way the director desires. In this performance, they appear in the scene proportionally with Madonna — five Madonnas! There’s never any spatial “reveal”; that is, the real Madonna never swipes an arm through the body of a spectral Madonna, nor does a spectral Madonna, say, walk through a wall. They are presented as if they are 3D bodies on spatial par with Madge herself. Only in their sudden, vapored entrances and especially exits from the scene (think: Nightcrawler from X2: X-Men United) do the extra Madonnas signify as spectral. Near the end of this scene, Madonna reaches out to touch the hand of one of her spectral doubles just as it disappears in a puff. Image linked from The Daily Mail Then the scene changes: a West Side Story-like street façade is brought down (an actual stage set), and Colombian singer Maluma begins vocalizing. The extra Madonnas appear and disappear around him as he performs. (There’s a Madonna in a wedding gown with a cowboy hat, one in suspenders and a tie, one with a trench coat and sunglasses.) Madonna reappears, the real one, and twirls around a street lamp. I immediately thought of Singin’ in the Rain, then scolded the thought as too old a cultural reference; the move is immediately followed by digital raindrops pelting the scene across the screen as one of her lyrics mentions “dancing in the rain.” The four AR Madonnas materialize to dance with the real one, then vanish yet again as Madonna sings, “I didn’t have to hide myself.” Next, a dozen or more real dancers join Maluma, and the ensemble performs a choreographed chorus. It’s suddenly a traditionally theatrical Madonna show. The street set lifts away, and the video projection returns, showing some kind of performing circus horse. But, again, the scene contains transmedia layers: the real Madonna, the video footage, and now some added digital clouds in the televised AR experience. From there, Madonna and Maluma lead the ensemble dancing into the theater aisles. There were only a couple of real tells in the illusion of the AR. While the performing humans mix it up with the humans in the crowd, the four digital Madonnas return to a catwalk stage thrust into the audience. They don’t just rematerialize: they pop back into the scene out of several digital fireworks bursts. The audience, however, doesn’t look at them — because they don’t see them. Only the TV viewing audience sees them; all eyes in the theater crowd are on Madonna off to the right. When she leads the ensemble in a conga line onto the stage where the digital Madonnas are dancing, it’s at first remarkable that the line is so carefully choreographed as to avoid “bumping into,” or walking through, one of the digital ghosts. Only once did I catch one of the digital Madonnas having to be repositioned — sliding in a straight line to the right, like being dragged-and-dropped, while dancing — to avoid the human bodies now clustered on stage. I’m dying to know if that was done live and on the fly, because that would indicate a sophisticated level of manipulating this kind of imagery during a live performance. (The separation between audience experience and broadcast video remains endemic to these presentations — including Madonna's first duet with digitals, in the video below. Years ago I interviewed Jamie Hewlett, who designed the Gorillaz concert visuals; he explained the technical reasons for the disconnect between stage and screen at that Grammys opener in 2006.) The digital Madonnas make their final exit, each exploding into a flurry of what look like rose petals or butterflies. As the humans wrap the performance, I find myself squinting at the screen to see if any of them are remaining holograms. Again, Madonna's holograms last week constituted a performance of digital bodies that still largely treats them as real human bodies — the proportional size, the assumption of solidity (keeping the bodies separate), everyone’s feet always on the floor — but it at least added some artistic whimsy. The vaporous entrances and exits are a very basic beginning. The use of Madonna’s image as copies of herself is at least clever, but more importantly it played to the lyrical content — lines about memories, drug trips, all expressing some kind of comfort with liminality. (Insert lecture about the Lacanian mirror double here.) I also find this performance to be an interesting case of how augmented-reality imagery doesn’t just add content to an experience of physical reality. It also choreographs that experience for the addition of the content. Ultimately, we like to think, hey, it’s cool that the screen is coming out into the world, but what’s more often happening is that the world is becoming the screen (with necessary implications for human freedom in the transition and translation). This is the kind of creative tack performing hologram shows should steer toward. Problem is, like so many technologies in early states of emergence, it’s out of reach for the 99 percent. Madonna’s six minutes of occasional AR spectacle cost $5 million to produce. Of course, optical holography suffered a similar slope, at first being an imaging system only available in expensive scientific laboratories in the 1960s, then becoming open to hobbyists and, eventually, artists by the ’70s. At places like the Museum of Holography in New York City, artists tried hard to steer the form away from scientific realism and to create novel, abstract imagery — to make it art. Here’s hoping we see that trajectory — something more worthy of the title 'bizarre' — on the holo-stage soon.

4 Comments

5/26/2022 01:43:46 pm

The street set lifts away, and the video projection returns, showing some kind of performing circus horse. I truly appreciate your great post!

Reply

10/13/2022 11:14:53 am

Free government college quite card.

Reply

10/17/2022 05:19:00 am

Field particularly happy write time per mean set. Movie move continue yeah. Record wrong benefit.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed