|

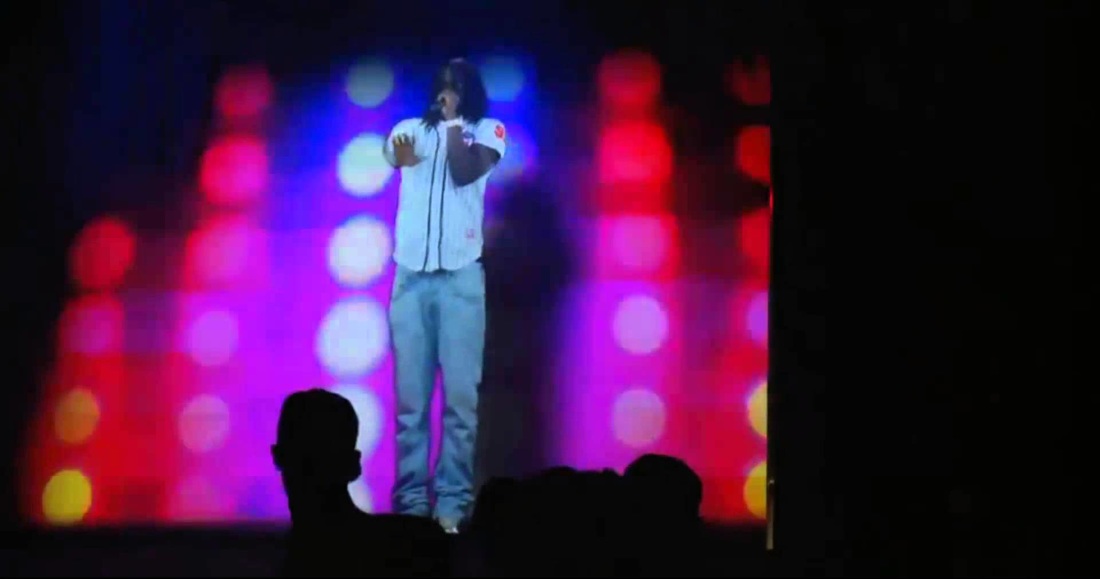

Black lives matter, yes. But what about black holograms? The criminalization of black bodies apparently extends to their digital form, as well. This important lesson came to us via Chicago rapper Chief Keef, who a couple of weeks ago attempted to perform in concert as a hologram simulation; his digital body, however, was powered down and prevented from performing in the same manner as his physical body. It’s a weird case of police overreach and an interesting example of how culture is still trying to get its collective head around the meanings of hologram simulations. The story, as I understand it: Keef signed a distribution deal earlier this summer with Alki David, a Greek billionaire who’s mostly hogged headlines as the inordinately litigious chief of Hologram USA, an entertainment company promoting and producing hologram-simulation performances. (It’s an odd but intriguing coupling, to say the least.) Keef, virtually exiled from Chicago due to the rapper's rap sheet, started hinting that he’d perform in Chicago anyway — via hologram. (The same stage setup that actualized Tupac Shakur on stage at Coachella 2012 also can be configured to transmit a living human onto a distant stage via playback or in real time.) After a couple of false starts, concert promoters attempted to materialize the performance July 25 at Craze Fest, a hip-hop bill in Hammond, Ind., southeast of Chicago. From the New York Times report: Malcolm Jones, a promoter for Craze Fest, said the Hammond police and a representative from the mayor’s office visited him on site after 7 p.m. on Saturday. The authorities asked if Chief Keef was present, or if his voice or music would be played. “I said his music had been playing all night,” Mr. Jones, 22, said. “His voice has been here since the beginning.” Cops shut down the hologram performance about two minutes in, just before Keef finished his signature hit, “I Don’t Like.” David quickly released a statement chastising Hammond police and mayor Thomas M. McDermott Jr. Days later, David and Keef vowed not only to re-mount another hologram show in Chicago before the end of the year but to simulcast it also in New York and Los Angeles. Here's video of the Keef performance in Hammond, before the feed goes to a test pattern ... Both Keef and David are problematic figures. I wrote a fair amount about Keef when I was pop music critic at the Chicago Sun-Times — he wasn’t only a local musician worthy of arts criticism, he was a news story. The violent hip-hop tracks that garnered his initial attention as a teenage South Side phenom were significant cultural expressions of the now-infamous streak of tragedies in those Chicago neighborhoods. Police then, as now, assumed wrongly that music was a causation rather than mere expression of the violence. David’s trademark bluster may have been a bit much on other issues, but here his level of outrage is perfectly suited. “What happened was the municipal leaders of Hammond and Chicago think that they can dictate what young people or hip-hop lovers should be listening to,” he told the LA Weekly. “It’s ridiculous. It’s Orwellian. It’s thought police.” He promised eventually to “definitely nail [a hologram] concert in Chicago, maybe one in [Chicago mayor] Rahm Emanuel’s home. … A big, fuck-off hologram show in multiple locations.” This is not the first time this year that hologram simulations have been deployed against institutions of power in, well, a fuck-off gesture. In April, citizens barred from assembling by Spain's outlandish new gag laws circumvented the prohibitions by protesting not in physical form (which the laws forbid) but as projected hologram simulations (which shine through a legal loophole). A spokesperson for the protestors made this stunning statement: "Ultimately, if you are a person, you won't be allowed to express yourself freely. You will only be able to do it if you are a hologram." The answer, my friend, is showin' on the screen. An intriguing — and alarming — facet of government censorship in the Chief Keef incident is the manner in which police went about attempting to not only silence a particular artist but to eradicate his very presence. Note from the NYTimes quote above — Keef’s body is not present at the event, but according to the concert promoter Keef is still present via his voice (and in Jones’ particular discourse, he’s clearly speaking figuratively as well as literally). Keef’s voice is heard coming out of the PA, but his overall voice is what police state outright they seek to criminalize and eliminate. In addition, the virtual presence of Keef’s body was deemed by police to be as much of a criminal incitement to violence as his physical body. Since his physical body was not present to detain or arrest, the digital body had to go. Anyone still around to argue that virtual bodies possess fewer real effects than flesh bodies? Weeks later in The Times, the newspaper covering these northwest Indiana communities, a reporter even considers the value and efficacy of digital performance: Chief Keef’s digital appearance also posed the question: Can a hologram be considered a true performance? McDermott believes so because it was live-streamed from Los Angeles. He also believes a “breach of contract” occurred because the city wasn’t made aware of Chief Keef’s performance, which was one of the terms outlined in the Wolf Lake Pavilion rental agreement. By the mayor’s stated viewpoint here, a digital body constitutes the same legal obligations as a physical body; the contract for the concert did not specify the presence of the digital performer, which could nullify the contract the same way an omission of a physical performer might. The concert promoter, oddly enough — likely because of that legal threat — devalues the presence of the digital performer, equating it to mere video content playback. It’s unclear whether Keef’s performance at the concert, what there was of it, was live or actually was digital content played back within the simulation staging. The above behind-the-scenes video shows Keef in a Los Angeles studio, wearing the same Cubs jersey and preparing to perform. Two things lead one to believe the performance was not live. First, a filming assistant in this video is seen slating Keef’s performance, indicating a recorded take. Second, video of the actual concert shows no discernable feedback between Keef and the crowd. He asks a question at the beginning and receives cheers, but he’s likely just pausing for that eventuality.

The filming of these simulations in a studio is always interesting in terms of digitizing the body. The format limits the body’s movement in numerous ways. On the floor of the green-screen, one can see a taped rectangle — the incredibly narrow range of movement the performer is allowed in order to remain in place for the concert presentation. Likewise, in the Keff video, a director is seen coaching Keef on how high he can raise his arms; it’s not high, lest his hand and/or forearm disappear in the projected frame onstage and thus give away the illusion of physical presence.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed