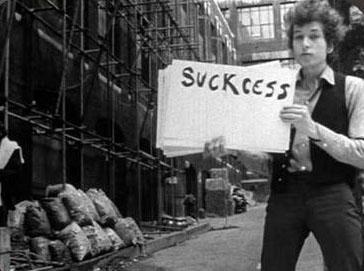

In a welcome break from election trauma, the usual Trump v. Clinton opining across my social-media feeds has been balanced this week by a different argument: “It’s high time Bob Dylan won the Nobel” v. “It’s a travesty Bob Dylan won the Nobel.” Even amid my curation of friends and followers — heavily weighted as each set is with fellow folks and folkies in the orbit of the Woody Guthrie Center and that same city's new Bob Dylan Archive — the split has been nearly half and half. Like the presidential polls, such overall ambivalence is surprising, particularly because this particular box of Pandora’s has been wide open for some time. What’s been especially astonishing to me, anyway, is the vehemence with which some fans — of literature, not necessarily of Bob — cling to an outmoded compartmentalization of mediated experience. Given the question that this news seems to have called, Dylan’s Nobel medal — since it appears he has no plans to collect it — ought to be exhibited someday next to Duchamp’s Fountain. Behold, two ordinary material objects that, by virtue of their enshrinement within certain sanctified spaces, opened idealistic rifts that reverberated across multiple classifications of culture. Even before Fountain, Duchamp had been bullied about Nude Descending a Staircase — now a Cubist classic, not to mention an important frame, so to speak, in the development of visual art’s representation of movement and dimension — and that was just over objections to its title. He subsequently snatched the painting from the Cubist Salon des Indépendents and whisked it away in a taxi, newly determined both to upend the art world’s hegemonic labels and to humble artists who believed they possessed some essential and extraordinary skill. He checked that off his to-do list five years later by installing Fountain, the urinal that pissed on pretension and relieved certain aesthetics of the everyday. There are parallels there, in reverse — Dylan, the Guthrie-inspired folkie lauded as artiste before his time and opting to weaponize the accolades rather than bask in them — and this week those frowning (yet again) at Dylan have turned ye olde “What is art?” question into “What is literature?” The answers are frequently disappointing. Granted, Dylan has been an easy cultural punching bag for decades — I've taken more than a few swings — and he rarely defends himself. Additionally, the timing of his magnanimous award is problematic. “A poet must be more useful than any other citizen of his tribe,” said Isidore Ducasse, Comte de Lautréamont — but Dylan’s usefulness to the broad culture may not appear exactly current. In 2001, not 1981, the Album of the Year Grammy was awarded to Steely Dan, two decades past the impact of their rock-Ellingtonia, an inevitable result of nostalgia and the merciless cultural imperialism of baby boomers. Both factors could be at play among members of the Nobel committee; however, it’s easier to showcase the considerable foothold Dylan’s work already has on university syllabi in and out of lit departments. Dylan’s impact, in other words, long ago reached beyond the Academy and into the academy. It’s also indeed criminal that no (traditional) American poet has yet received this particular Nobel (paging Adrienne Rich). Then again, as mentioned, we knew this was coming. The committee has floated the idea repeatedly. Critic Bill Wyman advocated for Dylan’s Nobel three years ago in The New York Times. One professor has nominated Dylan for the award every year for the last 12. Most troubling, though, are the isolationist viewpoints expressed in many of the arguments against Dylan’s honor. I apply the term isolationist here less to culture as a whole and more to the media through which we predominately experience it today. I’ve heard Dylan described, by way of defending his prize, as a poet — one who “happens” to play guitar. This fails as justification because it misunderstands not only the potential literary depth of Dylan’s work but the media landscape in which it operates. The playing guitar and singing isn’t a mere add-on to Dylan’s linguistic messaging; it’s a facet of the multimedia synthesis that contributes to its broader communication as well as a new message all its own — media being the message, etc., at least partly. A New York Times editorial this week bemoans Dylan’s award in text that is laughably get-off-my-lawn, very Grey-Lady, and utterly resistant to cultural times that have already a-changed: Yes, Mr. Dylan is a brilliant lyricist. Yes, he has written a book of prose poetry and an autobiography. Yes, it is possible to analyze his lyrics as poetry. But Mr. Dylan’s writing is inseparable from his music. He is great because he is a great musician, and when the Nobel committee gives the literature prize to a musician, it misses the opportunity to honor a writer. According to this kind of perspective — this is written by Anna North, herself a novelist trained at the traditionalist Iowa Writer’s Workshop — one can refer to written texts as lyrical and perhaps even musical, but the addition of actual melody (an embodied, sensory experience) immediately boots the text from the lofty perches of literature (a formerly purely idealist concept), dropping it into the underworld of mere music. This thinking stems from the obsolete idea of literature as purely textual, and it’s this crusty point of view that scholars of popular music and pioneers of cultural studies — Raymond Williams, Lawrence Grossberg, all hail Simon Frith, and to some degree public intellectuals like Greil Marcus — began fighting clear back in the 1970s. Frith’s seminal pop music scholarship argued “that it was possible to read back from lyrics to the social forces that produced them” (1989). In his early complication of that verb — to read — lurks a seed of the paradigmatic shift still under way as to what constitutes acceptable knowledges and their communicable forms. To wail about the decline of reading assumes a definition of it that’s aging out (painfully, granted, as this very post is written by someone who wrongly assumed that newspaper journalism would be a stable career). Our intricately networked multimedia systems assist in redefining the experience of communicating meaning and critical thinking, a new definition that de-centers the written text. Reading hasn’t ended — it’s evolved. Some of this smacks of technological determinism, and part of what compelled me to post about this news is that the common objections to it, typified in North’s hand-wringing, brought to my mind the man who wrote “media determine our situation” (Kittler, 1999). Friedrich Kittler, a literature scholar turned vaunted media theorist, has used rock music — the Fugs, the Doors, an exhaustive explication of Pink Floyd’s “Brain Damage” — frequently within his complex explanations of shifting media paradigms. Kittler began by applying discourse analysis to poetry, ignoring content in favor of the verses' meaning-producing mechanisms, which he said operated underneath and outside of language. This function appeared after an epistemic break, Kittler claimed, roughly aligned to that 19th-century change of (allowable) thinking mapped in Foucault’s Order of Things; but where Foucault’s epistemes broke without apparent reason, for Kittler the paradigm shift was enabled by changes in media practices. The same logic suggests another one in process now. Emerging digitally based practices blur the separate channels — text, sound, visuals, even touch are all now the surface effect of the underlying digital code. Individual media are marginalized by the whole digital apparatus. That’s a point of great angst for those with a conceptual or professional stake in the identity politics of media classification. For artists, though, who recognize the immense potential for new modes of expression emerging from media mergers — however initially conciliatory new media are toward former forms, that is, remediated (Bolter & Grusin, 2000) — the thought of experiencing culture via a single medium at a time is akin to mandating my millennial students to surrender their pocket computers and use only rotary phones. Dylan is “a bard exploiting the new-media inventions of his time (amplifiers, microphones, recording studios, radio) for literary performance the way playwrights or screenwriters once did,” writes Rob Sheffield in one of several Rolling Stone defenses of Dylan’s accolade. (No surprise that Rolling Stone, now the cultural equivalent of AARP The Magazine, is behind Bob, but Sheffield is a critic with a nuanced understanding of music’s media effects.) That Dylan might crossover from mere pop-music star to membership in the highest pantheon of human scribes means this intermedial way of life is gaining a prominence befitting its dominance. Efforts to answer this question are just getting started. As Sheffield advises, “So settle in. This argument will take us years.”

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed