|

Saul Bellow was born a hundred years ago today, and people of letters have been spilling a lot of them in appreciation of and retrospection on his considerable work as a very American novelist. As it happens, this spring is also the centenary of a pivotal moment in those same American letters — the expression of a problematic idea that still haunts cultural discourses and one that speaks directly to Bellow’s particular literary tactics: publication of Van Wyck Brooks’ claims about this country’s great divide between “highbrow” and “lowbrow” cultures. Media coverage of Bellow’s posthumous birthday has spotlighted Brooks’ problematic binary. A convoluted piece in the Chicago Tribune bears the headline, “Saul Bellow helped knit highbrow, lowbrow.” In the Wall Street Journal, the same sentiment’s a subhead, which is elucidated in the article: “A favorite device in his novels was to let a scoundrel drop a reference to Tocqueville or Marx, revealing an unexpected sheen of intellect and a touching hint of self-improvement. Bellow returned again and again to the juxtaposition of the highbrow and the lowbrow: the bookies and jazz musicians who dabbled in philosophy. But the low was his natural register; it was the boat’s hull and the ideas were just the trim.” That piece is a reflection on a new Bellow book, a collection of his nonfiction, titled, There Is Simply Too Much to Think About — as if the intellectual highbrow were attainable but exhausting (I’m a grad student — preach!), laborious rather than enlightening, and ultimately not worth the effort. But Bellow’s characters often made that effort painstakingly. It’s notable that one of those characters, a gangster, is described as “a cast-iron lowbrow.” But that’s just the object — it’s the predicate that tells the tale, that points to the performativity of movement between the poles: he “pretended to be a cast-iron lowbrow” (61, my emphasis).

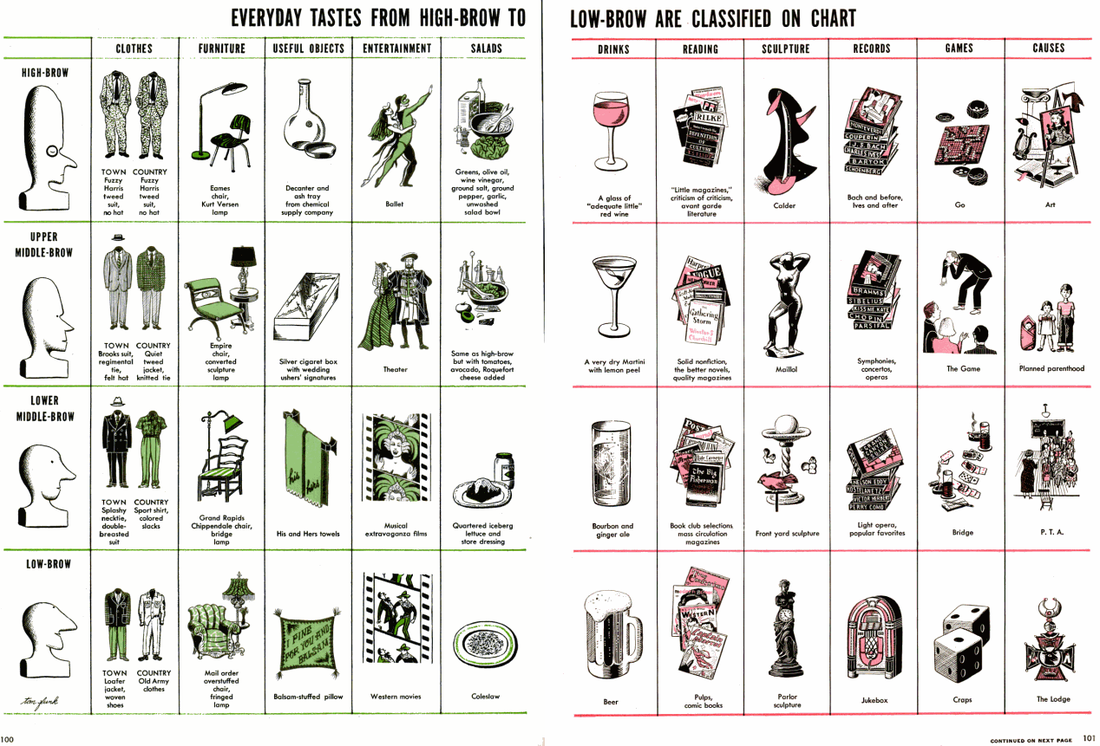

The binary pre-dates Brooks — it was already alive and kicking in Plato’s Republic while he went on about how life is to be “pursued in the spirit of a philosopher, and not of a shopkeeper!” — but was set into American stone via “Highbrow and Lowbrow,” Brooks’ essay published in April 1915 and virtually repeated in his second book, America’s Coming-of-Age, the same year. Brooks labels the two extremes as “quite American” (482), claims that no aspect of American life is undivided along this line, which separates “on the one hand a quite unclouded, quite unhypocritical assumption of transcendent theory (‘high ideals’); on the other a simultaneous acceptance of catchpenny realities” (483). He states this as fact, but he does not celebrate it. Both terms “are used in a derogatory sense” (483), and “they are equally undesirable” (483). That said, they are also the only options, for “there is no community, no genial middle ground” (483) between them. Middle of the road? That’s merely a transit corridor between two inevitable destinations, not a third category or spectrum. How did we Americans groom such bifurcated brows? Brooks ascribes it to our Puritan roots, almost precisely as Weber later defined capitalism, not to mention Merton in defining “the new science”; Merton, in fact, described the Puritan work ethic as a practice that “built a new bridge between the transcendental and human action” (113), drawing deeply from Brooks’ metaphor of spiritual highs and earthly lows — but again, not to reconcile and relinquish but to facilitate motion between. The American rags-to-riches hegemony, however, indicates a lowbrow-to-highbrow trajectory, and this seemed to work the nerves of high-culture advocates in the early 20th century. As mass communication bolstered mass culture, structuralism swelled and began demystifying high art. Terry Eagleton notes this in his survey of Literary Theory — “since deep structures could be dug out of Mickey Spillaine as well as Sir Philip Sidney, and no doubt the same ones at that, it was no longer easy to assign literature an ontologically privileged status” (93) — though it applied equally to other art forms, especially the popular music Adorno & Horkheimer loathed so. Without such an opening created for street-level expression, the Popular Front might have been relegated to the back burner. Brooks, though, cautioned against such mobility. If we go about “lifting the Lowbrow elements … to the level of the Highbrow elements,” we risk suffocating the lowbrow in the thin air of the highbrow. The result: “a glassy Inflexible priggishness on the upper levels which paralyzes life and turns its professors to dust; but that the lower levels have a certain humanity, flexibility, tangibility which are Indispensable in any programme” (491). We’ve knitted the brows in place ever since, and the binary continues to thrive within discourse. Just today, a Google News search delivers highbrow-lowbrow headlines covering topics ranging from TV comedy to the taste-testing of hamburgers. There’s even a new sociology study of musical tastes among class divisions, which finds “a homology between class position and musical tastes that designates blues, choral, classical, jazz, musical theater, opera, pop, reggae, rock, and world/international as relatively highbrow and country, disco, easy listening, golden oldies, heavy metal, and rap as relatively lowbrow.” (Love how reggae slipped into the highbrow. Highly Selassie!) Neatly slotted as those genres might be, though, this study may point toward the very “middlebrow compromise” Dwight Macdonald claimed, against Brooks’ objections. For I have seen Midcult, and its name is Shuffle. The random selection of tracks from a user’s library or an online service mixes highbrow and lowbrow together in one long middlebrow stream. Choral and classical are brought low by being sequenced with a country track in between; rock and rap harmonize. Divisions dissolve, definitions become meaningless. The remaining experience is a wash of, to borrow some Bellow, “frying jazz and the buzz of … butt-thumping.”

1 Comment

Leave a Reply. |

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed