|

I'll be teaching performance studies this fall — fresh off one of the most exciting examples of "doing things with words" I've ever participated in: the moment last week when my dissertation committee reconvened in my presence and announced that I am now Dr. Thomas Conner.

Boundless thanks to my chair and adviser, Dr. David Serlin, and my stalwart committee. We had a thrilling and heady conversation about holograms and "holograms," materiality and immateriality, physical things and digital things, living presence and spectral absence, and of course life and death. Exactly how I hoped this journey would find its end. Off to prepare scintillating job-market packets! Need a professor who can teach your wacky comm theory and your journalism editing lab? Inquire within! Read the abstract of my dissertation

1 Comment

Awfully quiet, this blog — because my writing energies are obviously elsewhere, now revising a dissertation (whew!). But somewhere during the last few weeks I answered a call from Zocalo Public Square to wax thoughtful about hologram technologies and media engagement. At this particular moment in history — when we're all thinking more consciously about mortality than usual — it's been interesting to read about ways technology has both upended and renegotiated death and funeral rituals. The awful iPad visits to a hospital bedside. The inclusive livestream of a funeral.

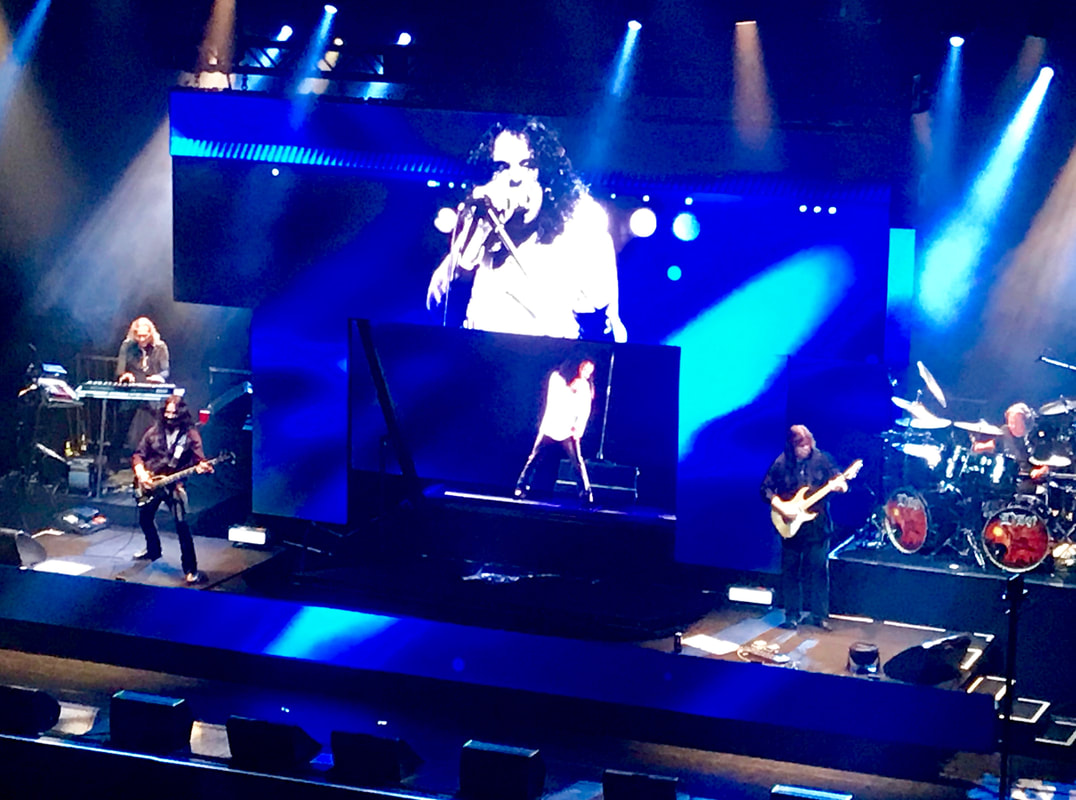

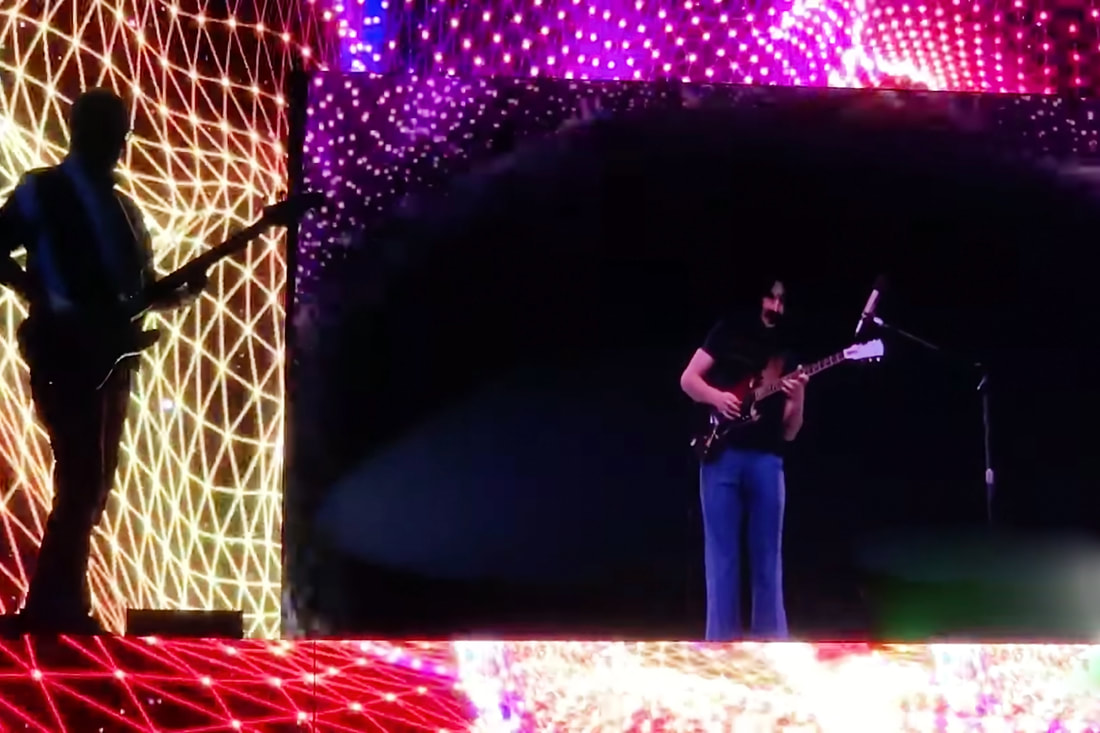

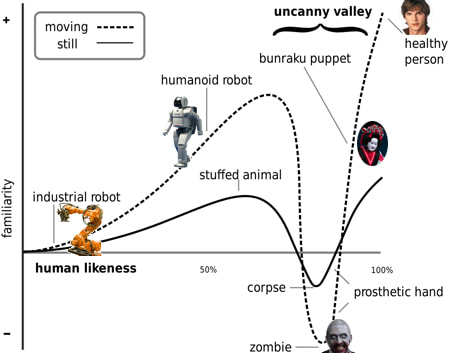

Given my own perspective on how media, specifically holograms, intersects with and helps shape these social moments, my essay published this week draws from my research to consider the potential trajectory of holograms of deceased performers on stages (i.e., Tupac) to holograms of late family members in the living room. Posted just in time for the holidays! Several iterations of performing “holograms” have begun touring the country, as I’ve written about a bit here (and it’s a primary subject of my dissertation). The rolling out of these nascent, futuristic spectacles constitutes early technical and market experiments to determine whether audiences will engage with posthumous, digital pop stars as a going concern beyond the one-off spectacles of 2.0Pac and Michael Jackson. The subject matter selected for this first round of touring spectacles has been, in a word, niche. For instance, the late soprano Maria Callas has been making the rounds of international opera houses once again, in digital form. Likewise, dead crooner Roy Orbison just completed new tours of Australia and North America, and last week it was announced his hologram will return to the road on a double bill with Buddy Holly. We're not starting with the Beatles, in other words. Last weekend, a hologram of heavy metal singer Ronnie James Dio wrapped a 17-date U.S. tour with a final show in Los Angeles. I attended that show, and I offer some thoughts and observations here. Image linked from Rolling Stone “The Bizarre World of Frank Zappa” is a current concert tour featuring a resurrection of the title rocker as a “hologram” — the latest in a lengthening line of the digital deceased returning to stages. For instance, rock and roll pioneer Roy Orbison toured again last year and opera diva Maria Callas sang earlier this month in Los Angeles, where next month you also can check out the controversial Ronnie James Dio hologram. Each of these is an offspring of 2.0Pac — the “hologram” of the (allegedly) dead rapper that landed a headlining slot at the Coachella music festival in 2012. They are augmented-reality (AR) displays scaled to life-size: a visual likeness of the original star is recreated digitally, paired with archived audio, and projected onto a stage where the image “performs” alongside live, human musicians playing in sync.

It’s a phenomenon that should be generating fascinating visuals, breaking a stale mold of live musical performance, and inspiring new modes of both living and posthumous embodiment. But it’s not, at least not yet. Performing holograms thus far — even zany ol’ Zappa — are alarmingly conservative in their presentation and undemanding of their phenomenological experiences. For a technology inextricably linked to discourses of futurism and spectacle, the first wave of virtual pop stars has been disappointingly old-fashioned and dull. This post argues for some perspectives that might assist and direct the creative development of Holograms 2.0, with a nod toward last week's more interesting televised Madonna holograms. I've written before here about David Gunkel's research and thoughts on the social rights of robots. He's now summed up the many arguments for and against — and contributed his own, based on the philosophy of Levinas — in a new book, Robot Rights, from MIT Press. I jumped at the chance to review it, and it's finally published online.

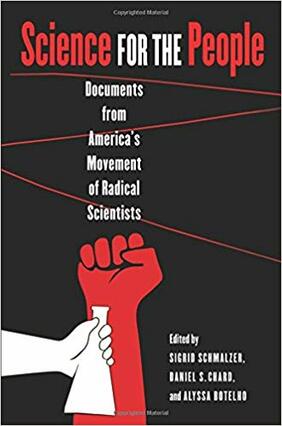

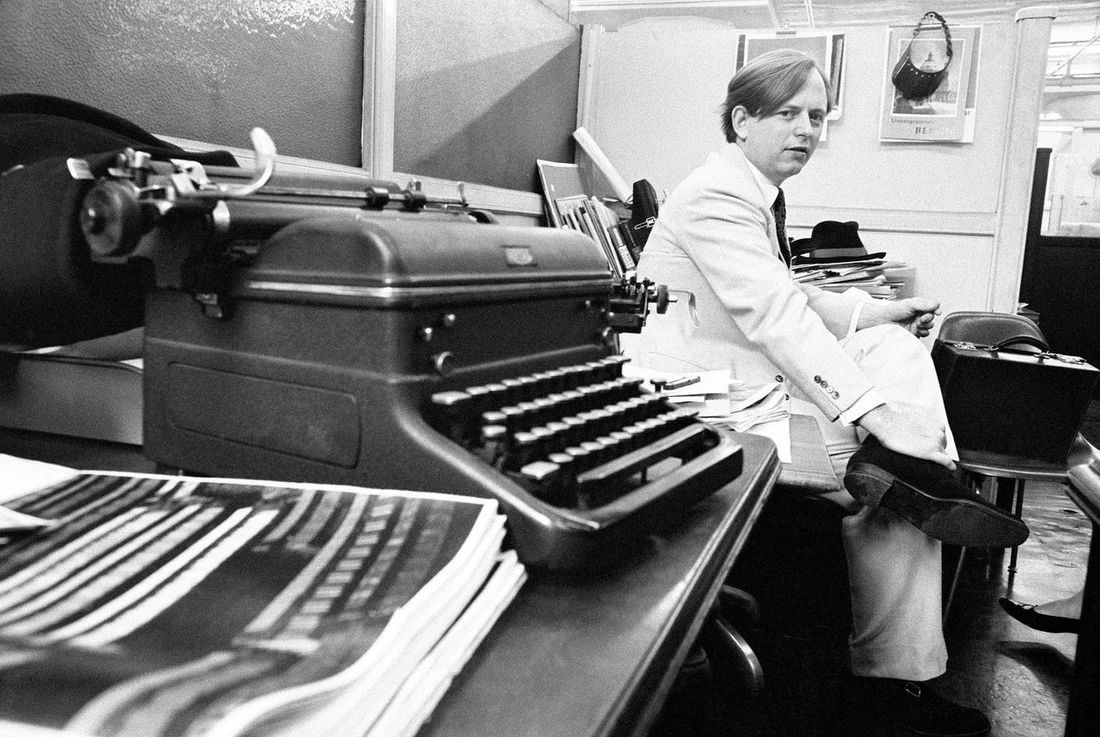

And, hey, Gunkel referred to my review as "positively brilliant"! Early in their experience, journalists — most of them, I believe, probably naively — often experience something of a reckoning. After some time assembling different combinations of the five w’s (who, what, where, when, and why) and sometimes the extra h (how), newspaper reporters realize that much of their work is not writing at all, not in any literary sense. They begin “trying to understand why the conventional newspaper story … fail[s] to capture the essential truth of the experience.” Because when you’re on a beat, you’re a short-order cook, slingin’ hash. There may be eight million stories in the naked city, but a cops reporter isn’t weaving narratives as often as she’s simply stringing together just the facts, man, and in less than 300 words, please. This epiphany can be positive or negative. It can lead to a change of career or a visit to the editor’s office to ask not for a monetary raise but an elevation in scope, opportunities with a bit more depth of narrative and space on the page. In the mid-20th century, a bevy of writers experienced a similar revelation at around the same time. Parallel to challenges to other social mores, these writers sought to break down and break out of the rigid AP pyramid standard for story structure. Novels had so many techniques, journalism so few: why not cross-pollinate? New and reimagined magazines, from Esquire to Rolling Stone, welcomed the experimentation. History classified their collective efforts as the New Journalism — and Tom Wolfe was the best of the lot.  Science for the People was an organization of scientists and science workers who banded together around the turn of the ’70s to express concerns about the commercialization, industrialization, and militarization of science. The group raised awareness of a multitude of issues, organized and balanced public debates (which sometimes included disrupting establishment conferences), and published a spiffy magazine for nearly a decade. Worried about how science was being used against people, SftP advocated for. In 2014, a conference was organized at UMass-Amherst to examine the group’s legacy. At the close of the event, several attending students and scholars from across the country met to discuss ways to continue the examination, even ways to revive and evolve the mission of SftP. I was fortunate to be among this group, and the result of our decision has finally been realized in a new book: Science for the People: Documents From America’s Movement of Radical Scientists, now available. My research focuses on technologies that bring digital projections of dead people “to life,” in a sense (or several). Part of my historical work tracks particular reasons the word “hologram” has been so easily applied to resurrected performances of, for example, Tupac and Michael Jackson, despite these presentations and their apparatuses having nearly nothing in common with actual holography. That is, they are not precisely related technically. The spectral imagery produced by both, however — the life-sized human bodies and parts of bodies that are there but not there — are part of a lengthy project in certain corners of human culture. Holograms and “holograms,” as well as the Pepper’s ghost stage illusion, certain representational concepts on either side of Renaissance art, on back to occasional practices at the Delphic oracle — these are technical presentations that both reckon with the dead and create a media effect I call “holopresence.” So the new film Marjorie Prime — a chamber drama about four characters swapping their mortal bodies for posthumous digital “holograms” — was, you might imagine, a must-see. (Spoilers to follow) “What year is this?” It was an extraordinary last line for a wide variety of reasons. Aside from those relevant to the narrative, it’s a question I hear asked often of pop cultural events. Like: “Nintendo is releasing a mini NES? What year is this?” “Billy Idol is opening for Morrissey? What year is this?” Even and maybe especially: “A new season of Twin Peaks? What year is this?” Sunday night’s anticipated finale of Twin Peaks: The Return capped an extraordinary run of television. That certain chunks of this 18-hour avant-garde odyssey are out there in the stream now — for everyday channel surfers to just stumble upon — blows my happy mind. This post is not a review of the show — there are plenty of good ones out there now — but just a quick knocking together of some thoughts about the series’ intriguing engagement with representational technologies and death. (And it does contain spoilers!) Attending San Diego’s famous annual Comic Con is a breeze — when you’re an STS grad student, at least. The lines for the Netflix trailers and movie sneak-peeks and TV cast conversations? Long, like crazy-long. The lines for the science panels? What lines?

I think I possess the very opposite of a macabre personality, but I’m thinking a lot today — in grave detail, shall we say — about my father’s corpse.  Jimmy LaFave left Oklahoma as a young man — just like one of his biggest heroes, Woody Guthrie — then lived an entire life continually inspired by the red dirt he left behind, haunted by his homestate histories, and consistently pressed into service as an ambassador for its culture. He didn’t seem to mind. “There’s something about that part of the earth that sticks with you,” he told the Tulsa World nearly 15 years ago. “I have to go back there from time to time to soak up some energy and inspiration. I plan to end up back there myself one day.” I don’t know if he’s ultimately ending up back in Oklahoma, but I’d always been convinced he never actually left.

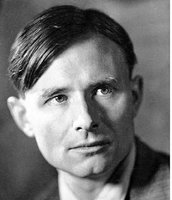

Throughout my life I’ve been a student of Christopher Isherwood. The avocation ranks as one of my supreme personal joys. Post-election, however — certainly post-inauguration — I find his subjective ruminations on Germany in the ’30s less abstract, starker, unsettling, more palpable. I’m beginning to recognize his texts in the world around me.

This should be a book lover’s joy. Not this time. Writing about Facebook profiles as memorials to the dead, Patrick Stokes notes that “our social identities are not necessarily coextensive with the biological life of the individual human organism with which they are associated, and thus it is not the memory of the dead person that is being honored and sustained through this form of memorialization, but some dimension or extension of the dead person themselves” (367). This is part of a growing body of literature that has coalesced around the agency of the dead — an agency facilitated specifically through durable, mediated representations of formerly living bodies.

My research is rooted in a sizable patch of this, but I’m commenting on some of it here because of a couple of nifty examples encountered just this week — mediated, shared, and hyped performances by two public figures who are no longer alive. (Warning: a few minor “Rogue One” spoilers lie ahead.) People think I don’t like Leon Russell, and nothing could be further from the truth.

It’s my own fault. On the way out the door as pop music critic for the Tulsa World newspaper back in 2002, I reviewed one of his shows and kinda let him have it. |

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed