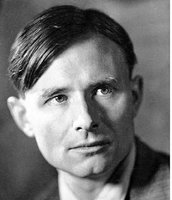

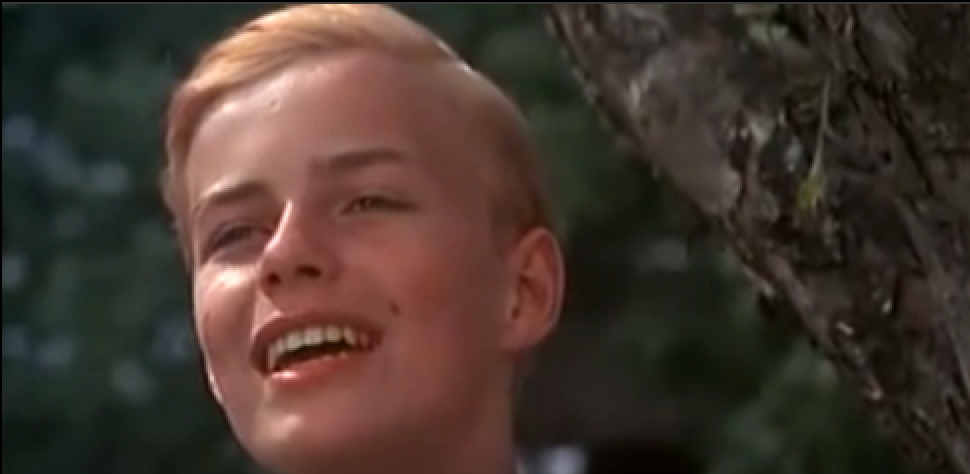

Throughout my life I’ve been a student of Christopher Isherwood. The avocation ranks as one of my supreme personal joys. Post-election, however — certainly post-inauguration — I find his subjective ruminations on Germany in the ’30s less abstract, starker, unsettling, more palpable. I’m beginning to recognize his texts in the world around me. This should be a book lover’s joy. Not this time. A skilled autoethnographer and, in a way, inadvertent cultural historian, Isherwood’s novels and later personal histories are invaluable chronicles of his particular contexts. Some of those observations were made while flitting around Europe as fascism took hold. His late-in-life memoir, Christopher and His Kind, was published in the mid-’70s and is an account of one man’s unapologetic escapades among the gay literati. Something like Quentin Crisp after him, but far deeper, Isherwood’s observations are dry, unassuming, eminently underlinable. Kind is a memoir of his arrival in Berlin in 1929, where he lived for four years, then of his movement about the continent until he and W.H. Auden emigrated to America in 1939. An upper-class Brit, Isherwood certainly didn’t need to go to Berlin. He went for the same reason they all did in ’29: free love. He romanticized the bejesus out of it, too: “When the German passport official asked him the purpose of his journey,” he wrote about his arrival (Kind is written in an objective third person, referring almost to a second self as “Christopher”), “he could have truthfully replied, ‘I’m looking for my homeland and I’ve come to find out if this is it.’” But ideas of homeland and horror dawn slowly, and the increasingly politically aware passages strike a familiar chord here and now: After Edward’s visit, Christopher became increasingly aware of the kind of world he was living in. Here was the seething brew of history in the making — a brew which would test the truth of all the political theories, just as actual cooking tests the cookery books. The Berlin brew seethed with unemployment, malnutrition, stock-market panic, hatred of the Versailles Treaty, and other potent ingredients. On September 20, a new one was added; in the Reichstag elections, the Nazis won 107 seats as against their previous 12, and became for the first time a major political party. This passage pretty much describes some Americans this month: Germany is pretty bloody. This Revolution-Next-Week atmosphere has stopped being quite such a joke and somehow the feeling that nothing really will happen only makes it worse. I think everybody everywhere is being ground slowly down by an enormous tool. Hindenberg appointed Hitler chancellor, and Isherwood struggles to hold out hope that Hitler ultimately will fail: Christopher, like other optimistic ill-wishers, kept repeating that this appointment was a blessing in disguise; Hitler would now have to cope with the economic mess, he would reveal himself as the incompetent windbag, he would be forced to resign, and the Nazis would be forever discredited. Months later, he realizes that he was — and all Europeans were — now through the looking glass: On March 23, the Reichstag was bullied into passing the so-called Enabling Act, which made Hitler master of Germany. In a mad, meaningless way, his successive steps toward absolute power had all been legal. What a question to consider: what is my homeland? Even worse is the sense of a creeping realization that the place you’ve lived your whole life may not be your homeland anymore, that the future — distant or, more likely, intermediate — holds an Isherwood-like journey (possibly by force, or fleeing) to resettle, reboot, and reimagine. How does one recognize when such a time has come? Isherwood's privilege allowed him the space and time to ponder such questions. Others, he knew, were denied such freedom, and we're likely beginning to see the same perilous quandaries in the United States. Before that realization, though — the numbness, the shock, the bleak and hypnotic reveries. Christopher and His Kind was a memoir drawn from the same life experience that produced the first two books that made Isherwood famous. The second of those, Goodbye to Berlin — a novel (’39) that became a stage play (“I Am a Camera,” ’51) and then a musical (“Cabaret,” on Broadway in ’66 and the great film in ’72) — ends in just such a state: Today the sun is brilliantly shining; it is quite mild and warm. I go out for my last morning walk, without an overcoat or hat. The sun shines, and Hitler is master of this city. The sun shines, and dozens of my friends — my pupils at the Workers’ School, the men and women I met at the I.A.H. — are in prison, possibly dead. But it isn’t of them I am thinking — the clear-headed ones, the purposeful, the heroic; they recognized and accepted the risks. I am thinking of poor Rudi, in his absurd Russian blouse. Rudi’s make-believe, story-book game has become earnest; the Nazis will play it with him. The Nazis won’t laugh at him; they’ll take him on trust for what he pretended to be. Perhaps at this very moment Rudi is being tortured to death. Fascism counts on such paralysis. In the film version of Isherwood’s tales, fascism’s awakening is depicted with a subtle, graceful horror. Directing duties for the movie adaptation fell to Bob Fosse, a dancer, and thank heaven. The visual effects of this film — all camerawork and cuts, no “special” effects — are fleet of foot, still a thrill even all these years after the MTV aesthetic conquered all. “Cabaret” piled up Oscars that year: Fosse actually beat Coppola’s “The Godfather” for the director award, and it’s utterly justified. You rewatch an old favorite, you see new things — present things. Fosse made a wicked picture about wicked fun, but his true art lies in the finessing of the story’s slow-burning political menace. A bit of mise-en-scéne … Brian (Michael York) and Maximilian (Helmut Griem), their dalliance just revealed to the audience, apparently have ducked away for a little romance. Inexplicably, they’re at some kind of country fair — in a field, a small crowd, crafts, food, beer, music, dancing. They’re leaning over a checkered tablecloth, cementing their forbidden desire by toasting a planned trip to Africa with the clink of glasses bright with sweet Riesling. York is young and delicious and somehow deeply tan, smart in seersucker shirt and tweeds. Then, an angel begins singing — a tenor voice, creamy as quark cheese, regaling the pastoral scenes with complementary verses about the sun, the meadow, a stag running free. The picnicgoers are transfixed. Fosse’s brilliant back-and-forth cuts start cycling, building a catalog of doughy Germanfolk faces, all arrested by the a cappella music, attentive, listening. There’s our singer now: a handsome but not striking teen, a mole on his left cheek (a beauty mark if ever there were), confident, fit. He’s striding through the song with trained grace and a winsome smile, his face firmly in the left third of the screen (perfectly satisfying cinema’s “rule of thirds”). He’s blond, of course — dishwater with a hint of strawberry detergent. We catch just a glimpse of his tan collar. Then the camera begins to droop, tilting down. His kerchief, neatly knotted. The thin, black leather shoulder strap. Now, there it is: the swastika arm band, its red stripes bursting in the frame like a ripe wound. Under his right arm, a cap with an insignia. Now the camera pans left, drifting back into the crowd, faces old and young, straight out of Zentral Gießen. The song goes on about the leafy green banks of the Rhine, and as it mentions a baby in its cradle an oompah instrumental support arrives. The verse leaps an entire octave. Cut back to the singing boy’s face, and now it’s on the right. He’s not alone, either: cut to two steel-jawed brutes standing, singing along, in lockstep as it were. The singing boy — now he doesn’t appear to be smiling at all, but straining, pushing his voice hard, no longer entertaining but informing, loudly, his white teeth starting to flash, his brow now furrowed. A girl stands up to join the vocal throng, hard-faced, her brows knit, looking every bit as if in a decade she’ll snatch an author off the King’s road and smash his ankles with a sledge. The song modulates again, more instruments join. The majority is singing along now, on its feet. We see a young woman in a lovely blue dress rocket from seated to standing, so suddenly that she jostles an elderly man seated next to her. He looks up, startled but perhaps not surprised. He does not stand. He leans over his mug of beer, slightly shakes his head — less out of disbelief than, well, maybe he can at least clear this noise out of his ears. He scratches his cap, wondering how it all came to this. A tide clearly has turned. Drums now, and the boy’s face has swelled within the right side of the frame. His pastoral tune has become a threat: “The morning will come when the world is mine!” The old man is small, hunched over his beer, his hand on his head, staring desolately into space. Everyone else is singing along, mouths agape, making sure their voice too is heard, and counted. My God, the song modulates again, and our boy’s voice is amazing, high but definitely not feminine, an angel indeed — but hawkish, bringing not peace but a sword. Our first long shot of him: he’s decked out in full evil-Boy Scout regalia, knickers, high socks, yards of itchy brown. The chorus touts the “fatherland,” the rhythm marches them all to battle. The boy puts on his cap, and his right hand snaps up into the rigid Nazi salute. “Tomorrow belongs, tomorrow belongs, tomorrow belongs to me!” Brian and Maximilian now have realized it’s time to amscray. Cut to the two of them pausing before climbing back into Max’s fine automobile, his chauffeur holding the door. Max had earlier dismissed the Nazis as nothing to worry about; Brian, taking one last look back at the scene, now can’t help but ask: “You still think you can control them?” It’s rhetorical, and their car pulls away. Then — fuck Fosse’s great — we get a quick cut of the MC, Joel Grey back at the cabaret, slowly lifting his fiendish whiteface to leer directly into the camera, like a vampire over his quivering prey, nodding slightly (the opposite movement and determination of the old man). He knew this was coming, see. He was a distraction all along. We should never have trusted him. The peaceful countryside fades into oblivion.

1 Comment

Joe

3/16/2017 01:56:13 am

I came here because i was looking for references to Christopher Isherwood's time in Berlin. It was meaningful to me to see that you quoted the last paragraphs of Goodbye To Berlin. Those words have resonated in my mind so many times as I have watched the same social changes Isherwood described coming to life in America recently. Thank you for doing what you can to help make people aware of it.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed