|

In many of my media-studies courses, we usually begin by underlining the idea that all communication is mediated. Some students initially resist this. They see conversation and face-to-face interactions as direct, unmanaged, unmediated — communing rather than communicating. Once we get going, though, they learn to see the mediation in play even here: gestures and visuals, language itself, social forces, and the very spaces of interaction. There is no mind meld. There’s always a mediator.

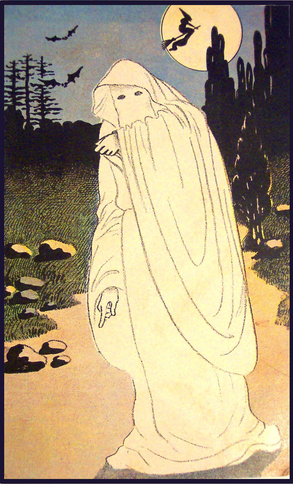

Many emerging media, however, would like their users to think like those hesitant students — to experience the pre-programmed interactions of their technologies as unmediated, to ignore the inherent and carefully managed structure of the encounter, to assume that the communication is direct and free of outside influence. Thus the rapid development of digital channels that seem more “natural.” ChatGPT and other AI systems free users from having to learn a particular communication code; instead of mastering the art of the Boolean query in order to maximize Google results, ChatGPT speaks our language, as it were. Ask it a complete, “normal” question, and receive an almost human response rather than formatted results. Siri, Alexa, and other voice assistants create seemingly interpersonal encounters via natural language, as if we’re conversing easily with another subject rather than interrogating a bot. Only when the systems make mistakes do they become more visible in the exchange and remind us that, oh right, I’m talking to a machine. To further understand this kind of situation — and especially in the context of my investigations related to digital holograms, which only succeed as communication if their mediating apparatus is similarly hidden from the user’s experience — it may be useful to adopt a theory that was coined in the context of literature and art and adapt it within media studies: demediation.

0 Comments

Last day of Media History class, and I threw ’em a one-two punch. First, we read some of Vilém Flusser’s intentionally provocative media philosophy — where he claims that the age of writing is ending. Then, per the 21C prof handbook, we pivoted to a YouTube video (above) about hip-hop writing practices. The class basically started with writing — what was it? what is it? what does it do? — so I wanted to bookend the semester by circling back. After spending the second half of the term immersed in mostly electronic media, indeed, what’s the status of this allegedly foundational linear-narrative form? Ever since I read this book in 2022, I’d been looking for the right syllabus — OK, any syllabus — that could support its wonderful weirdness. Written by a musician, it’s one of the finest theoretical texts about cultural materialism I’ve ever savored. And it’s all about a spent piece of chewing gum. In the early 1990s, folk-rocker John Wesley Harding released one of the best B-sides around: “When the Beatles Hit America.” A lengthy narrative about a dreamed-up Fab Four reunion, it envisions both cultural and technological contexts for a new Beatles event — and this is back when only one of them was dead. In Harding’s epic ballad, the Beatles are going to reunite on stage, all “due to a miracle marketing strategy / beyond the realms of reasonable possibility.” The lyrics realistically dramatize the build-up (securing the film rights, sponsorships, talk show scheduling, etc.) and then inject a bit of scifi to make it happen (the manager of the new Beatles is “made up of cloned parts of Col. Tom Parker and Col. Sanders”). Ringo won’t actually play, though, because he’s been replaced by a more accurate drum machine; he’s “disappointed to find that no one / needs him anymore except for the vibe.” Lennon, meanwhile, is substituted with a life-size cardboard cutout, and then — per today’s news, in a way — he speaks to the press, sounding suspiciously like some old recordings: John, who was never the quiet one makes all his press contributions from his old songs -- in tune, in time, and with the backing track behind him And when they ask him how it’s been in the studio, he says, “It’s been a hard day’s night” And no one understands him, but he always was the cryptic one … Funny stuff, but now prescient. Today marks the release of the Beatles’ latest — and allegedly last — technologically resurrected cast-off, a “new” old song called “Now and Then” that features the two living members and the two dead ones reunited in eerily perfect harmony and time. As a scholar who studies the uncanny properties of media and its inherent constructions of liminal spaces between life and death, well, I have some initial thoughts. If you’ve arrived here after clicking the link on Twitter: Greetings! You’ve reached the Twitter handle of Dr. Thomas H. Conner. I currently am unavailable to service the social-media labor needs of a neofascist CEO and his tech bros. Please join me in not leaving a message there.

The following post points to other places you can find me & my work, as the Feelies sang, for a while anyway … When I was the pop music critic at the Tulsa World in the late ’90s and early aughts, I had the distinct pleasure of meeting and writing about one of my musical heroes, Dwight Twilley ("I'm on Fire," "Looking for the Magic," "Girls"). The ol' cuss passed away recently, and I returned to the World's pages this weekend to try and say something about what I learned from him — like, how to be proud of where you come from without coming off like a chamber-of-commerce goon. Twilley's pop-rock sound was Tulsan, pure and simple. He knew it, he understood it, and he hired the guys to maintain it. (Different than Leon Russell or J.J. Cale and all that "Tulsa Sound" stuff. Dwight was just nine years younger than Leon, but somehow I think of Leon as an uber-boomer and Dwight as a bit more forward-thinking.) Here's to you, DT.

It's the first week of classes at The University of Tulsa, where I'm a new Visiting Assistant Professor of Media Studies. My upper-division seminar is Music as Social Action, a theoretical and historical survey of American protest songs. And wouldn't you know it — a protest song just went viral around the country. Given this confluence — and the fact that stories about the song keep tagging Woody Guthrie and Billy Bragg, with whom I have some considerable personal experience — I had some thoughts. My colleagues at the Tulsa World were good enough to print them.

(Initial, tweeted reactions to the Apple Vision Pro rollout ... )

This has been one small step for Apple, one decent-sized leap for augmented reality. And this is the inevitable thread of my initial thoughts about this week’s Apple Vision Pro launch … A new journal article of mine is now published: "Rock and Roll Will Never Die: Holograms and the Spectrality of Performance" in the spring issue of Spectator, the film-studies journal at USC. The work extends a conference presentation I gave at USC's First Forum in 2021. The abstract: In 2012, the rapper Tupac Shakur performed in the top slot at a major music festival — an event only notable because he had died 16 years earlier. The performance was made possible by a 21st-century digital upgrade of a 19th-century stage illusion called Pepper’s Ghost, and it ushered in a trend of creating and presenting similar “hologram” performances of posthumous pop stars. This article offers an explanation of what is seen in such a performance, examining the simulation of 3D video imagery designed to veil its mediation in order for its subject to appear unmediated, present, and “real.” Ultimately, I claim that these illusions are contemporary séances — a revival of historically spiritualist practices but one in which what is conjured is actually the deceased’s previously existing performing persona, as the concept has been extended by Philip Auslander. This cultural entity (distinct from the body and able to outlive it) is offered a new embodiment within a media system that restores the immaterial entity to the material space of the stage — a context previously off limits to the dead performer. Read the article here!

I thoroughly enjoyed being a guest on this podcast this week, Star Warsologies, to discuss my historical research on holograms. Star Wars, after all, is the source code for our contemporary denotation of the term "hologram." Those two scenes of Princess Leia's futuristic video-mail in the first film overwrote existing understandings of holograms, changing colloquial notions from optical kitsch to computer projections. Today's headlines and even research routinely name-check the princess imagery as a ready-made identifier for projects attempting to actualize that scifi imaginary. Thanks to hosts James Floyd and Melissa Miller for a lively conversation about all things digital and spectral! Check out the episode here: With the dissertation behind me, I’ve managed to fill some of my spare research time with a personal project — family genealogy. I’ve been setting aside notes and data for decades, and this summer I committed to connecting the dots and ferreting out the stories. Somehow I timed this right, life-wise. My research muscles are well-trained now — in a lot of historical method, no less — and university library access really enhances the verification (and, more often, debunking) of the often suspect data found through online genealogy databases.

Among the curious tales unearthed thus far, I discovered that while I might be the first “doc” in the family, I’m not the first published academic. Raffi Kryszek, of PROTO Hologram, and myself before the panel at SDCC22. What a great time hosting a panel at Comic-Con in San Diego on Friday! A sizable crowd joined us for "From Scifi Imaginary to Tech Reality: The New Science of Holograms" — and, wow, did they ask superlative, knowledgeable questions! Panelists were myself and Raffi Kryszek, the principal hardware architect for the PROTO Hologram company in Los Angeles. (Tara Knight from Colorado U's Critical Media Studies program was unable to make it.)  I finally got the chance to show off one of the only vintage comic books I possess: a 1978 one-off called Holo-Man, about a doctor zapped by high energy in a holographic matrix, which grants him superpowers (projecting illusions, time travel, invisibility). We parsed the various ways holograms have remained ubiquitous throughout science-fiction narratives, evolving the imaginary of digitally projected matter and characters. Then Raffi discussed the exciting work being done at PROTO to actualize that imaginary — creating life-size, photo-real 3D simulations of people through its unique "hologram" technologies. He even clued us into the next new model (desktop-sized!). Good stuff and good fun! Thanks to the Comic-Con folks for having us! In this week’s episode of the CBS crime drama NCIS, detectives interview an unusual person of interest in a murder case: the victim herself.

Older narratives might have made this possible via a traditional spiritualist séance, with interested parties holding hands around a table as Madame Blavatsky channeled the spirit of the dead in order to ask directly, “Whodunnit?” In today’s séances, however, the medium has become digital media: complex technical imagery systems that archive a person’s likeness and prerecorded messages intended to be posthumously played back for survivors. Several such apparatuses exist already, though most are still in experimental and prototype stages. This NCIS episode, however, brings to the broader public a fairly accurate depiction of what such “holograms” currently look and seem like, as well as providing some early fodder for conversations about how they might be integrated into social realities. That is, people often ask, “Why in the world would you make a hologram of yourself?” Here’s a pop-culture text that starts grappling with a few real answers. Get Back — Peter Jackson’s extraordinary new reboot of Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s 1969 documentary footage following the Beatles’ penultimate recording sessions — has been revelatory in numerous ways, from its prompting of astute reconsideration of Yoko Ono’s much-maligned cultural narrative to final proof that Billy Preston utterly saved the day. The remarkable technology used to revive these old reels (and the audio) is important to attend to not only for its importance to the future of film restoration but for its increasing intrusion into filmmaking; Get Back is a highly computed film, perhaps the first movie many have seen with such dramatic and artistic contributions by an algorithm (“And the Oscar for Best Algorithm goes to…”?) — to the point that the documentary’s rotoscopic computation of imagery and sound can be seen as the construction of a kind of virtual reality.

In addition to this surface virtuality of the image, however, I’m interested in the virtuality of the individuals shown through that imagery — and the ways Get Back is less a documentary about live human beings than it is about a socially constituted band of living ghosts. |

this blahg

I'm THOMAS CONNER, Ph.D. in Communication & STS, and a longtime culture journalist. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed