music as social action ::

the Blog

|

We just talked about Kate Smith, whose 1939 recording of "God Bless America" drove Woody Guthrie to respond in kind with his own song that became equally iconic, "This Land Is Your Land." Smith, who died in 1986, recently landed at the center of a lyrical firestorm. What could possibly be controversial about her old nationalist chestnut?

For many years, it's been a tradition at several American baseball parks and hockey stadiums to play Smith's version of the patriotic song during games. Several teams, however, announced last week that they will play someone else's recording of "God Bless America" from now on. This is because some other songs that Smith recorded — in particular, two songs called "That's Why Darkies Were Born" and "Pickaninny Heaven" — have come to light and caused new offense. The first song stems from a Broadway revue and had been performed and recorded by a number of artists, including a version by black Civil Rights leader Paul Robeson. Read literally, the lyrics are easily construed as quite racist; others, however, have suggested that the song is satire or biblical allegory. The incident is interesting for us as we transition from the Smith era of popular song, in which singers like her usually chose (or were instructed to sing) songs written separately by songwriters, to the era of the more subjective — and, as Rosenstone's reading suggests, inevitably more political — singer-songwriter. When you're not singing your own words, are you always fully conscious of their messages and meanings? We've also discussed how the meanings of songs (and covers of them) evolve as they are performed in different historical contexts. Kate Smith may have had no problem singing these songs when very different social mores dominated the country. Today's norms may have encouraged different results, or at least a different conversation.

2 Comments

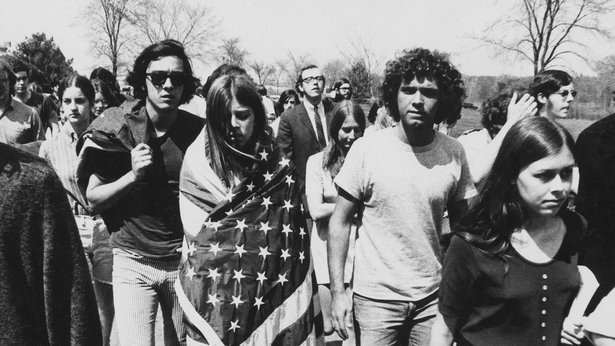

As we approach the 1960s in America and zero in on how pop music connected with the issues of the era — as well as why the imagery of the ’60s protest singer has wielded certain power over later generations of musical protest — there are countless sources of literature and documentary film attempting to summarize and contextualize that particular social scene. Notably, famed documentary filmmaker Ken Burns' latest multi-part installment: The Vietnam War. The 10-episode series aired via PBS and is available currently to watch on Netflix. For our immediate situation, it may be of interest to examine what music not only was chronicled by the documentary but was used on the film's soundtrack itself. To that end, PBS previously compiled some Spotify playlists of the music featured in each episode. In addition, music journalist David Fricke has written liner notes for the series' soundtrack, which can be read here. In this text — which covers and comments on an impressively wide variety of music, some of which we've discussed thus far — Fricke pushes some well-traveled discourses about how rock music was inextricable from the experience and understanding of the United States' involvement in that war, even going so far as to claim that "Vietnam was the first rock & roll war." Note, too, the way Fricke discusses the double-natured communication of some songs, specifically the way a cover by another artist (from another social group) changes and/or adds layers of meaning to the original — as we've begun to examine. Also, this consideration of music during the Vietnam war may be of interest, especially the author's initial comparison of music written and utilized during WWI and that during the Vietnam war, how each worked to foster unity in certain ways. Participation! In the interview with Theodor Adorno that we watched, he says that a protest song about the Vietnam war is unbearable — not based on a musical criticism but because, in his view, something as serious as a war should not be trivialized as a pop-culture commodity. How might he react to someone referring to the conflict as a "rock & roll war"? What work is being done — and on behalf of whom — when a war is framed in this way? Just a program note: The BBC has just aired a new short documentary about Woody Guthrie. Titled "Woody Guthrie: Three Chords and the Truth" — a phrase borrowed from punk culture — this hourlong special relates the general background and life story of the famous American folksinger. It's handy for any of you looking to learn more about this pivotal figure, and it includes a previously unreleased recording that was recently discovered.

One of the film's creative consultants is Will Kaufman, author of the excellent book Woody Guthrie: American Radical, one of your optional readings from last week. (Of extra interest: read about the song Woody wrote railing against Donald Trump's father, "Old Man Trump," which Kaufman came across in the archives of the Woody Guthrie Center.)

For your first assignment, you chose a song and applied theory from our class and readings thus far to determine what elements of protest and/or propaganda it manifested. Your choices of songs ranged widely — some typical choices from the canon of topical pop, plus a few interesting ideas and creative defenses. We're off to a good start!

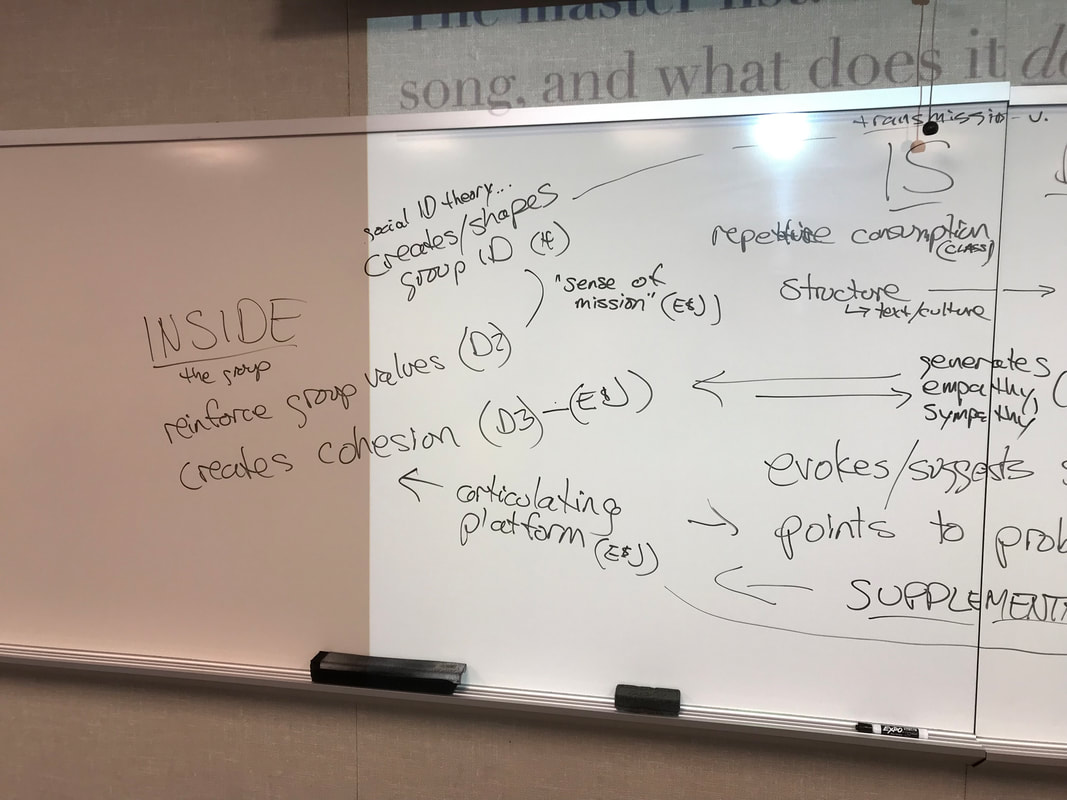

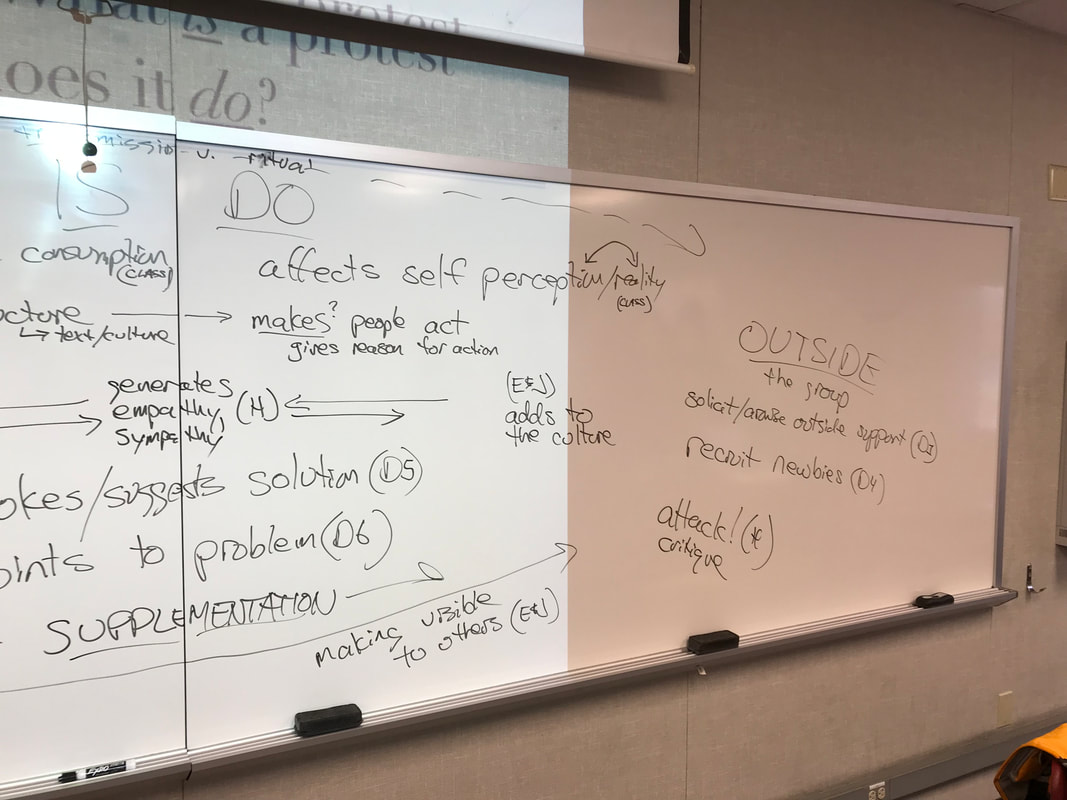

Here's a playlist of the songs students selected for the first assignment: Plus, I couldn't locate one student's selection on Spotify, but here is a YouTube video of it: As we wrap our initial theory dissection and begin turning toward a relatively chronological view of topical-music history in the United States, here are a couple of accessible pieces that make good introductions to this work: (1) the story of "John Henry," one of the most popular American folk songs, and (2) an account of when it was always hammer time in folk music. Participation! In regard to the first piece, about John Henry — Think of a pop song you know and/or like that tells a story about a fictional character. (Examples: "Eleanor Rigby," "Major Tom," "Mr. Wendal," "St. Jimmy," or, relevant to us next week, Nina Simone's "Four Women"!) What is the story and theme of the song? Why did the author(s) choose to relate a fictional character instead of a real person? What work does a literary narrative do that a documentary account couldn't? Excellent work today! Your leaning into the theory readings paid off for us all in a generative discussion and the production of the beginnings of criteria for our object of study — a list of what a protest song is and what it does.

What follows is a textual round-up of today's in-class theoretical mashup, as well as my hasty photos of what you all contributed to the board ... A speaker is visiting campus this week who may be of great interest to us. Favianna Rodriguez is an artist and activist in Oakland — chiefly a visual artist, however the posted description of her talk asks questions that parallel our work in this course: Culture is power. Culture surrounds us all the time. It shapes our identity and forges our collective imagination. How does art inspire new ways of thinking? How can art support social justice movements? Her talk is at 2 p.m. Thursday at The Loft in the Price Center. There are snacks! Register to attend here — it's free — and I may see you there.

Participation! If you attend, tell us about it. How does her perspective align with ours? How does it differ — what can her art and activism add to our discussions? Our class discussion was cut short before I could share this bit about another Woody Guthrie song important to transmitting information about certain social groups as well as ritualizing the maintenance of those identities: "Plane Wreck at Los Gatos," known colloquially as "Deportee." A recording by Woody is not available to stream, but here's a version by his pal Pete Seeger. The song tells the story of a plane crash near Los Gatos, Calif., on Jan. 28, 1948. Woody was living in New York City at the time, and he read in The New York Times about the crash that killed 32 people. Only a few of those people, however, were named in the story: the white flight crew and a white security guard on board. The others were migrant workers from Mexico, who on the plane because they were being deported. Because their names were not listed, their families were not identified. Wood was moved to write a song about their plight, not just on the plane but in the culture. Without names to sing, he takes some poetic license and gives them symbolic ones: Juan, Rosalita, Jesus, Maria, etc. Listen to Seeger's recording of the song — think about what exactly is being protested here, and how? Fast forward to 2009: Tim Hernandez, an author/poet/professor, was in a Fresno library researching a book, and he spotted an original newspaper article about the crash. "Who were the people on that plane?" he wondered. "Did anyone ever tell their loved ones why they didn't come home?” A marker for the anonymous bodies was erected in a Fresno cemetery that read simply: “28 Mexican citizens who died in an airplane accident … RIP.” Hernandez decided to do the detective work to identify all 28 people. He found many of their survivors, learned their stories, and wrote a book celebrating their lives. He still speaks around the country, sometimes performing with other musicians, and when he talks about this story he reads the list of all 28 names. Watch that here (can skip to about 4:12): This week, you read your first selections from Dorian Lynskey’s 2011 book, 33 Revolutions Per Minute: A History of Protest Songs. Here's a fairly recent interview with Lynskey — a Q&A that deals with many questions relevant not only to your reading of her work but to the overall arc of the course. (Pay particular attention to a question midway through about the history of culture wars, which is a topic next week!)

Participation!: The general question being considered in this interview is whether or not the increased activism of the Trump presidency thus far has revived the spirit of protest music. Have you heard new protest songs in, say, the last year or so? Tell us about them, and include links! In our first class discussion today, we brought up the concept of culture and how it can be divided into different levels, which can then be claimed (ideologically) by certain social groups. In other UCSD comm courses, you've likely encountered the work of Stuart Hall, who was instrumental in creating the scholarly field of cultural studies — one of the first academics to suggest that the study of popular culture was as important as examining so-called "high" culture.

Consider that (alleged) difference between "high" and "low" culture, how those delineations have been presented to you, and where you straddle that line in your daily experience. Previously, on my personal blog, I looked back at a 1915 essay that was influential in establishing that binary — and the lasting effect it has on America's view of itself and its culture. Participation! Read the Van Wyck Brooks essay linked there (or here). What do you think about his perspective on American culture? Do we still divide the culture between this binary? For what purpose — what work is that doing, and for whom? |

COMM 113T

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed