music as social action :: Blog

|

I couldn't have ordered up a more fascinating capstone for the ideas and theories we've discussed in class this term. Alas, we've missed most of the shows — what a field trip this woulda been! — but be sure to read all about this. (And, hey, if you have friends at UCLA, drop everything and head up there this weekend for the final show!) Taylor Mac is a performance artist who's been creating some challenging multifaceted stage work and art for more than a decade. He won a genius grant last year, which he's apparently used to stage a 24-hour, 24-decade history of American popular music. Broken into four six-hour installments, Mac has been showcasing the width and depth of humanity's historical use of music to express, counter, and queer ideologies. He's attempting to present a history of the United States, but in concert song rather than written text or documentary film. Much of what we discussed in class is at work here — the things music can do that other texts can't, the ecstasy of a performance spectacle, perhaps even a different context for social-group cohesion. This L.A. Times article is a good summary, and check out this staid but thorough PBS report on the show ...

0 Comments

Many of you who selected the “creative” option for the course's final project — writing and recording your own protest song — are to be commended for taking the leap. A few of you said you’d never dreamed of even doing such a thing. Scary, eh? But a bracing (and educational) plunge! In the interest of walking it like I’ve been talking it, I’ll share here a protest song I wrote and recorded when I was (forgive the old-manism) about your age. During my undergrad senior year, I took it upon myself to take up the guitar. Dubbing myself THC and styling myself as some earthy nerd, I embraced the home-recording trend of the early ’90s and started making “records.” An unfortunate series of cassettes and CDs followed. The following song is from the first homemade tape, Kwitcher Bitchin (circulation appx. 32 copies). “Lip Service” attempts to make a call (on behalf of all gay men, audaciously) for less political talk, more political action — an explicit statement of the direct-action criteria we saw suggested by Denisoff on forward. That is, sure, sing your songs because of the other functions they support (group cohesion, external communication of ideology, recruitment, etc.), but eventually go do something, too. Alas, the action I'm calling for in the song is, er, indistinct. Recall that we discussed that problematic, too ... (Technical caveats: The sound’s not great, a bit distant, a digital transfer of a home-stereo recording from near-countless generations of audio technology ago. First take, flubbed chords. I was in some hurry, don'tchaknow. Lyrics take a dark turn at the end. New Dylan, I ain’t.)

As always, production thanks to David “I Should’ve Been the One to Teach Them GarageBand Basics” Zachritz South by Southwest is an annual music conference and festival — a event at which artists and their record companies can showcase themselves in a kind of one-stop shopping for the music industry and media. Todd Martens, a great critic at the L.A. Times who covers SXSW each year, posted this piece in advance of this week's five-day festival. His thesis is that SXSW this year also will be showcasing a great deal of political communication via the music.

As you read his article, note where our course theory pops up — in the way a couple of artists describe the inevitability of their writing songs of social protest given current events, in the ways artists are thinking about (and afraid of) feedback with their audiences, and in claims such as "these songs are about building a community." Participation! Why would current events seem inevitable for the production of protest songs? Setting aside personal political responses to that, think about it in terms of our course theories. Why, in an era of so many varied means of communication, would people turn to music for this type of expression? Answer with an example of a very recent protest song — why is it a particularly effective means of communication? (For sources, see this video reel of numerous recent tracks, or this piece about new protest songs.) Since our week 8 hopscotch through various musical mega-events in the 1970s and especially ’80s, several of you have asked follow-up questions about the ultimate impact (politically but also financially, which was its chief stated mission) of the Live Aid concerts in 1985.

I'll refer you to two pieces: — This media article from The Atlantic a couple of years ago is a fair retrospective of Live Aid's cultural legacy, such as how the concerts crafted a template other fundraisers have followed. — This scholarly article from a journal attempts to survey Ethiopians who would have been infants at the time of the famine (and, as we saw, such imagery was a prime motivational tool in the fundraiser's marketing) and gauge how their lives were impacted by the relief efforts. The short answer: not much.

Here are all the embeds curated by the class for the annotated playlist assignment. Be sure to peruse them and come to class with any through-lines you spot — other than the prevalence of Kendrick Lamar (whew!), what are the commonalities to the songs students selected? Importantly, how would you suggest that these service our evolving list of social-action functions?

(Note: if a playlist has less than the assigned 10 songs, it's because Spotify does not include the particular songs and/or artists that student had selected.) A recent trawl through The New York Times picked up a couple of articles relevant to our recent discussions and readings:

1. Superchunk is a pop-punk band (there's one of those cagey hyphens!) that's been around for decades, and in all that time they have never been known for taking overt stances on social issues. Their new album, however, has been getting a good deal of press based on the fact that it is political. The NYTimes' headline is typical of the discourse being circulated by fans (and/or the band's PR): "It took Trump to make Superchunk go political." In the piece, you can read numerous assumptions we've already encountered, such as the idea that "[m]ost protest music is terrible. It’s pedantic, it’s usually preaching to the choir," as well as the expectation that the social upheaval Trump's election would unleash a lot of protest songs. Especially ahead of next week's topics, note the song that Mac McCaughan says is "questioning what good did all that punk rock do?" (The album is streaming temporarily here.) 2. The new Marvel superhero movie, "Black Panther," is generating a lot of headlines about its foregrounding of race within a white-dominant corner of pop culture. That extends also to its soundtrack by Kendrick Lamar, which works "to hint at the movie’s story while concentrating on tales of struggle and swagger much closer to home." Consider here how the goals of an individual artist operate through this prime example of the culture-industry machine: where does Lamar's voice end and Marvel/Hollywood commercialism begin, or can that binary even be discerned? (The soundtrack is now on Spotify.) A brief Q&A published yesterday by NPR addresses this class in substantive ways. In it, the network's music critic, Ann Powers, discusses the failure of Timberlake's halftime show — not based on artistic merit but because he was specifically not political.

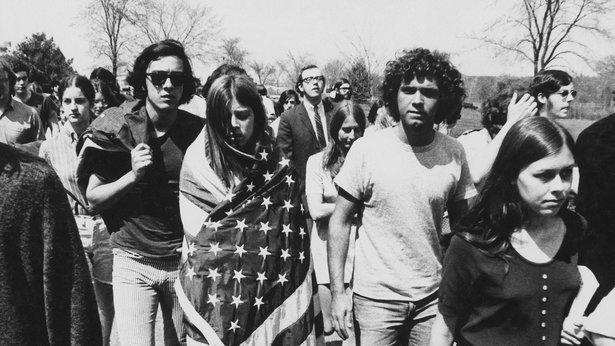

Cast your mind back to the Super Bowl performance in 2016. Remember Beyoncé's spectacle, its racial encodings, its occasionally overt discourses about systemic American violence? Remember the backlash that struck within hours? Conservative pundits found the show "outrageous," and not in a good way. The combination of musical text and costumed subtext constituted, for some, a "Black Lives Matter rallying cry." Beyoncé was celebrated by some for her stance but scorned by many simply for bringing (black) politics into a (white) leisure space. (This New York Times columnist evaluated the day's histrionics in an astute piece that mentions a historical example of racial imaging — precisely the type Stuart Hall discusses!) So what now to make of criticisms of a white pop star for not being political enough in the same literal and figurative arena? Where is the middle ground, and who could possibly claim it? Powers asserts that "we are living in a moment of struggle, and we want our pop music to also reflect that struggle." Really? (As is always important to ask amid these kinds of discourses: who's the "we" she's claiming this for?) What's changed in two years to contribute to this about-face? "We want statements and struggle in our pop music, not just another smooth dance mix," she concludes. The goal of this course is to chart how and when that actually might be the case. What kinds of statements of struggle do we want in pop music? Who's "we"? In what situations do they contribute to social change? Why do those messages succeed or fail? Does medium matter? Crucially, when might statements of struggle not be welcome in pop? And when — as we'll begin seeing examples of this week and especially next — does "just another smooth dance mix" actually become political despite the intentions of the artists and producers? (Hit it, Martha!) As we approach the 1960s in America and zero in on how pop music connected with the issues of the era — as well as why the imagery of the ’60s protest singer has wielded certain power over later generations of musical protest — there are countless sources of literature and documentary film attempting to summarize and contextualize the social scene. Notably, last fall saw the premiere of famed documentary filmmaker Ken Burns' latest multi-part installment: "The Vietnam War."

The 10-episode series is available for viewing to PBS subscribers. For our immediate situation, it may be of interest to examine what music not only was chronicled by the documentary but was used on the film's soundtrack itself. To that end, PBS has compiled Spotify playlists of the music featured in each episode. In addition, music journalist David Fricke has written liner notes for the series' soundtrack, which can be read here. In this text — which covers and comments on an impressively wide variety of music, some of which we've discussed thus far — Fricke pushes some well-traveled discourses about how rock music was inextricable from the experience and understanding of the United States' involvement in that war, even going so far as to claim that "Vietnam was the first rock & roll war." Note, too, the way Fricke discusses the double-natured communication of some songs, specifically the way a cover by another artist (from another social group) changes and/or adds layers of meaning to the original — as we've begun to examine. Participation! In the interview with Theodor Adorno that we watched, he says that a protest song about the Vietnam war is unbearable — not based on a musical criticism but because, in his view, something as serious as a war should not be trivialized as a pop-culture commodity. How might he react to someone referring to the conflict as a "rock & roll war"? What work is being done — and on behalf of whom — when a war is framed in this way?

For your first assignment, you chose a song and applied theory from our class and readings thus far to determine what elements of protest and/or propaganda it manifested. Your choices of songs ranged widely — some typical choices from the canon of topical pop, plus a few interesting ideas and creative defenses. We're off to a good start!

Here's a playlist of the songs used in the first assignment: One student's selection isn't available via Spotify: Eminem's "The Storm" freestyle can be heard here. This week, you read your first selections from Dorian Lynskey’s 2011 book, 33 Revolutions Per Minute: A History of Protest Songs. I mentioned this class would cross paths with current events, right? The Atlantic just this week published an interview with Lynskey — a Q&A that deals with many questions relevant not only to your reading of her work but to the overall arc of the course. (Pay particular attention to a question midway through about the history of culture wars, which is our topic for next week!)

The general question being considered in this interview is whether or not the increased activism of the Trump presidency thus far has revived the spirit of protest music. Have you heard new protest songs? Tell us, and include links! |

COMM 190

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed