music as social action ::

the Blog

|

The focus of this course is pop music — usually spotlighting individuals at the mic, or bands, at the most. But what is different or (to align with some of our readings) useful about music made by larger groups of people? Bob Dylan singing a song is one thing, but we've already seen how the effect and even the messaging itself can change when, say, "Blowin' in the Wind" is sung instead by a hundred people at a protest march.

To wit: the San Diego Women's Chorus performs two shows this weekend of direct interest to some of our discussions. The concert, "Quiet No More: A Choral Celebration of Stonewall," acknowledges this year's 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Inn protests, which made public the social movement for gay rights. The music being performed an an eight-movement piece commissioned for the occasion, which tells the story of the Stonewall events through music, plus a few other selections. Tickets can be purchased here — $18 for students, but add the promo code "UCSD" to obtain what I'm told may be a significant discount. The shows are at 7 p.m. Saturday and 4 p.m. Sunday at Lincoln High School, 4777 Imperial Ave.

1 Comment

Well, this was kind of the universe: As we prepare today to transition from punk to hip-hop, here's a brand new podcast about the Clash narrated by Chuck D! "Stay Free: The Story of the Clash" is a new eight-part series developed by the BBC for Spotify. The pairing of Chuck D with the subject is not incongruent. As explained here, Chuck D founded the hip-hop group Public Enemy amid discourse about wanting to be "the hip-hop version of Joe Strummer," the figurehead of the Clash. There's also a related playlist. In this course, we focus our discussions primarily on the content of pop music's communication. We rarely talk about the ontologies of the various media delivering that communication. Amid our discussion of disco, I mentioned the following mini-documentary, which delves into precisely how some of the content of that genre was altered by a significant material change in its packaging as a product. This is interesting for our overall theories (and may be of interest if you're curious about vinyl records, past or present) ... Participation! What are the differences for the experience of music messaging between physical media and streaming access? That is, previous generations had the option of acquiring and owning physical products (records, cassettes, CDs) in order to hear recorded music, or they could simply listen to what was played on the (free) radio. How does that compare with today's primary options of buying digital music files and paying for access to streaming services? How does either experience improve or limit the messaging, especially of political subjects? "Real Time with Bill Maher" is a weekly current-events chat show on HBO, hosted by the namesake comedian/pundit. Apropos of perhaps little, in the segment below — an extra Q&A he does with his guests especially for YouTube — Maher reads a viewer's question for the pop musician Moby, "Do musicians have a responsibility to use their platforms to influence politics?" (starting at 2:40) ... Moby's response is quick and highly subjective, but it's interesting for us in the ways it highlights something we've mentioned a few times but not drilled down on. We've discussed the commercial aspects of making and selling music with political messages, but in a broader sense. Moby makes it personal, focusing on those who might not want to make political waves for fear of upsetting their income and career, for the sake of their family. We just talked about Kate Smith, whose 1939 recording of "God Bless America" drove Woody Guthrie to respond in kind with his own song that became equally iconic, "This Land Is Your Land." Smith, who died in 1986, recently landed at the center of a lyrical firestorm. What could possibly be controversial about her old nationalist chestnut?

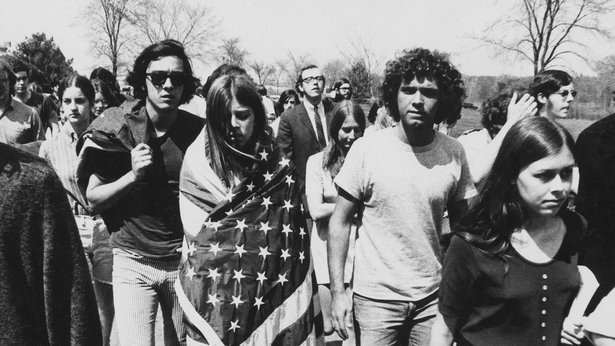

For many years, it's been a tradition at several American baseball parks and hockey stadiums to play Smith's version of the patriotic song during games. Several teams, however, announced last week that they will play someone else's recording of "God Bless America" from now on. This is because some other songs that Smith recorded — in particular, two songs called "That's Why Darkies Were Born" and "Pickaninny Heaven" — have come to light and caused new offense. The first song stems from a Broadway revue and had been performed and recorded by a number of artists, including a version by black Civil Rights leader Paul Robeson. Read literally, the lyrics are easily construed as quite racist; others, however, have suggested that the song is satire or biblical allegory. The incident is interesting for us as we transition from the Smith era of popular song, in which singers like her usually chose (or were instructed to sing) songs written separately by songwriters, to the era of the more subjective — and, as Rosenstone's reading suggests, inevitably more political — singer-songwriter. When you're not singing your own words, are you always fully conscious of their messages and meanings? We've also discussed how the meanings of songs (and covers of them) evolve as they are performed in different historical contexts. Kate Smith may have had no problem singing these songs when very different social mores dominated the country. Today's norms may have encouraged different results, or at least a different conversation. As we approach the 1960s in America and zero in on how pop music connected with the issues of the era — as well as why the imagery of the ’60s protest singer has wielded certain power over later generations of musical protest — there are countless sources of literature and documentary film attempting to summarize and contextualize that particular social scene. Notably, famed documentary filmmaker Ken Burns' latest multi-part installment: The Vietnam War. The 10-episode series aired via PBS and is available currently to watch on Netflix. For our immediate situation, it may be of interest to examine what music not only was chronicled by the documentary but was used on the film's soundtrack itself. To that end, PBS previously compiled some Spotify playlists of the music featured in each episode. In addition, music journalist David Fricke has written liner notes for the series' soundtrack, which can be read here. In this text — which covers and comments on an impressively wide variety of music, some of which we've discussed thus far — Fricke pushes some well-traveled discourses about how rock music was inextricable from the experience and understanding of the United States' involvement in that war, even going so far as to claim that "Vietnam was the first rock & roll war." Note, too, the way Fricke discusses the double-natured communication of some songs, specifically the way a cover by another artist (from another social group) changes and/or adds layers of meaning to the original — as we've begun to examine. Also, this consideration of music during the Vietnam war may be of interest, especially the author's initial comparison of music written and utilized during WWI and that during the Vietnam war, how each worked to foster unity in certain ways. Participation! In the interview with Theodor Adorno that we watched, he says that a protest song about the Vietnam war is unbearable — not based on a musical criticism but because, in his view, something as serious as a war should not be trivialized as a pop-culture commodity. How might he react to someone referring to the conflict as a "rock & roll war"? What work is being done — and on behalf of whom — when a war is framed in this way? Just a program note: The BBC has just aired a new short documentary about Woody Guthrie. Titled "Woody Guthrie: Three Chords and the Truth" — a phrase borrowed from punk culture — this hourlong special relates the general background and life story of the famous American folksinger. It's handy for any of you looking to learn more about this pivotal figure, and it includes a previously unreleased recording that was recently discovered.

One of the film's creative consultants is Will Kaufman, author of the excellent book Woody Guthrie: American Radical, one of your optional readings from last week. (Of extra interest: read about the song Woody wrote railing against Donald Trump's father, "Old Man Trump," which Kaufman came across in the archives of the Woody Guthrie Center.)

For your first assignment, you chose a song and applied theory from our class and readings thus far to determine what elements of protest and/or propaganda it manifested. Your choices of songs ranged widely — some typical choices from the canon of topical pop, plus a few interesting ideas and creative defenses. We're off to a good start!

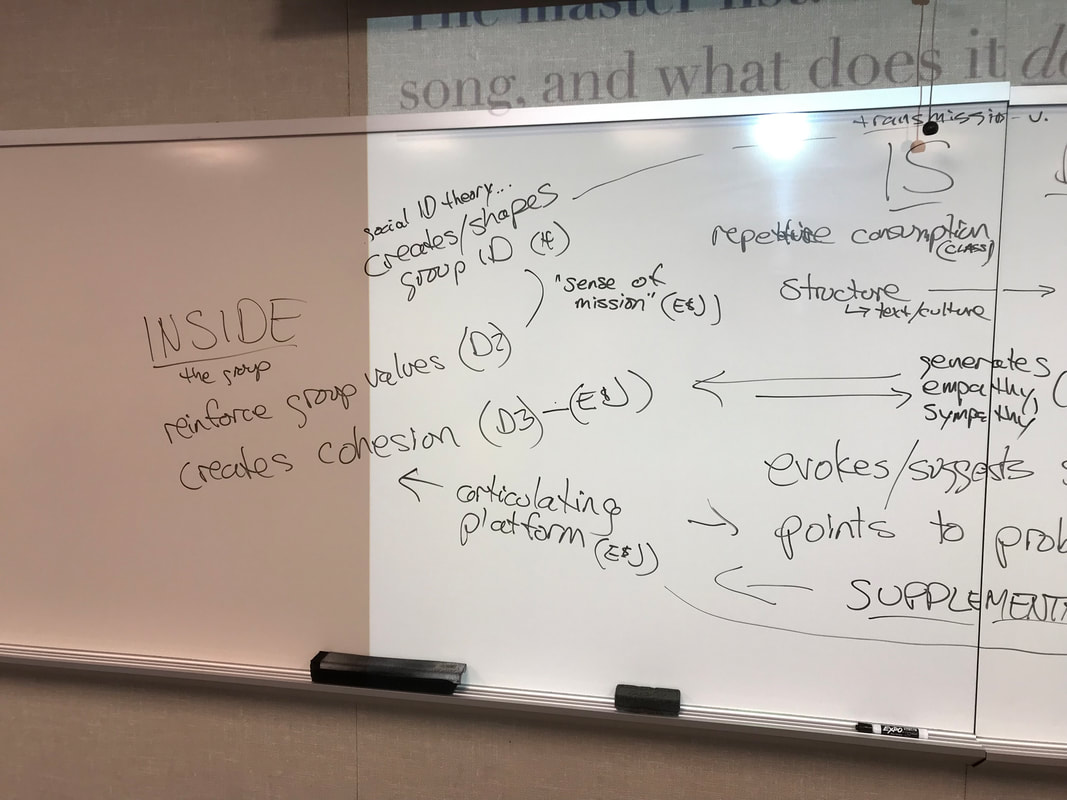

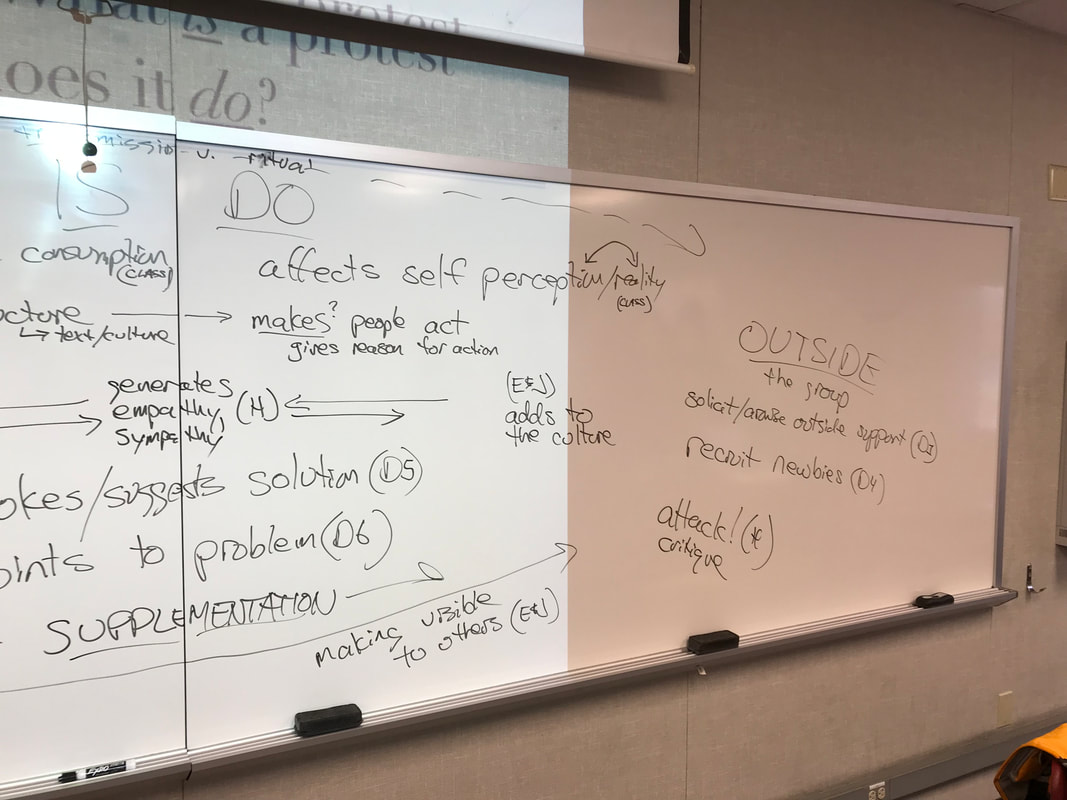

Here's a playlist of the songs students selected for the first assignment: Plus, I couldn't locate one student's selection on Spotify, but here is a YouTube video of it: As we wrap our initial theory dissection and begin turning toward a relatively chronological view of topical-music history in the United States, here are a couple of accessible pieces that make good introductions to this work: (1) the story of "John Henry," one of the most popular American folk songs, and (2) an account of when it was always hammer time in folk music. Participation! In regard to the first piece, about John Henry — Think of a pop song you know and/or like that tells a story about a fictional character. (Examples: "Eleanor Rigby," "Major Tom," "Mr. Wendal," "St. Jimmy," or, relevant to us next week, Nina Simone's "Four Women"!) What is the story and theme of the song? Why did the author(s) choose to relate a fictional character instead of a real person? What work does a literary narrative do that a documentary account couldn't? Excellent work today! Your leaning into the theory readings paid off for us all in a generative discussion and the production of the beginnings of criteria for our object of study — a list of what a protest song is and what it does.

What follows is a textual round-up of today's in-class theoretical mashup, as well as my hasty photos of what you all contributed to the board ... |

COMM 113T

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed